It’s commonly stated that nudism, as it is practiced today, “stems from a movement of the exaltation and extension of functional nudity.”1 Since the 18th century, various hygiene specialists saw nudity as healthy and endorsed bathing in water, sun, air, and light. The “bathers” tacitly agreed to limit all behavior that was suggestive, erotic, or sexual. At certain eras, however, there existed forms of collective nudity where the motives weren’t health or even physical or moral comfort, but the desire to rupture with humanity in the direction of what was “superhuman” or “subhuman”: of angels or beasts.2

Group practices of this kind existed in the Gnostic movement in the first centuries of the Christian era. Certain sects practiced chaste nudism, and others a libertine version. The followers of the former wanted to hasten a return of Jesus Christ and the Kingdom of Heaven by reproducing the original conditions of Adam and Eve in earthly paradise. Saint Augustine held as much disdain for these “Adamites” as for their libertine counterparts, writing, “the men and women gather naked; naked, they listen to sermons; naked, they pray; naked, they celebrate the sacraments and in doing so think that their church is paradise.”3 In the opposing group of libertine nudism, the Carpocratians showed their contempt for the world – which they thought the work of inferior angels – by endorsing all immodesty.4 In doing so, they thought they were working their way towards God. These two forms of Gnostic nudism share the commonality of constituting a way of life, rather than a transitory state.

It’s hard to believe that an ideal of permanent nudity, where the principal figures are Adam and Eve on one hand and Diogenes and Carpocrates on the other, could have contributed to the development of modern nudism. Marc-Alain Descamps, to whom we owe the first French study of national and international nudism in 1972, warned that “the first misconception to avoid concerning nudists is on the very nature of their goals and practices”: “[n]udists aren’t against clothes, [t]hey don’t deplore their invention or demand their abolition.”5 Nonetheless, the author offers a glimpse of other premises of nudism when he affirms that nudists regard Francis of Assisi as a patron saint.6 Saint Francis ruptured with the “merchant” world of his father and undressed before Bishop Guido’s court. Even if the bishop quickly wrapped his coat around him before giving him a peasant’s shirt, Saint Francis’ symbolic gesture of permanently shedding his clothes lends itself to a perspective of permanent nudity.

Aspirations of this type can be found in the “prehistory” of German nudism, between 1885 and 1909.7 The first proponents of socially acceptable nudism, which came later, took care to specify that they weren’t preaching permanent nudity unlike some “extreme fanatics of nudity.”8 For instance, the “reasonable” nudist Dr. Johannes Große explicitly rejected permanent nudity for physical, mental, and hygienic reasons in the pro-nudist journal Die Schönheit (Beauty, 1903-1932). Apart from a tan, which was considered hideous and socially debasing, the major risks were the loss of sexual desire or, on the contrary, the “bestialization of sexuality” through overexposure to other people’s nakedness.9 In 1905, another writer in Die Schönheit specified that nudists undress only “when circumstances expressly invite it,” notable for bathing or swimming.10 This pragmatism of “reasonable” proponents is strikingly different from the extremism of certain pioneers.

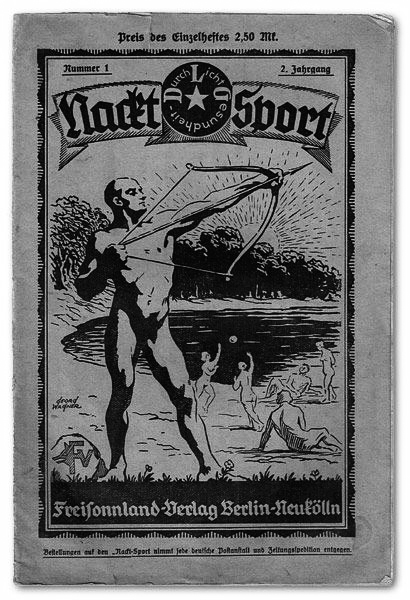

Nackt-Sport, 1920, periodical of the Berlin “Free Body Culture” (FKK), under the editorial direction of Fedor Fuchs.

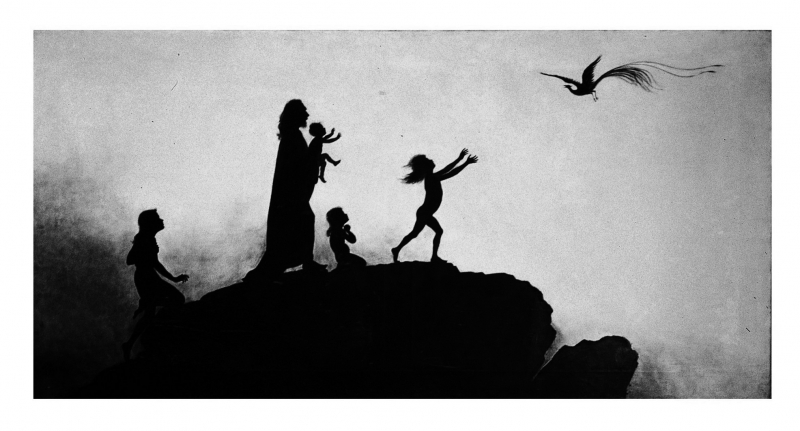

Karl Wilhelm Diefenbach (with the assistance of Fidus), Per aspera ad astra, silhouette imaged mural of 34 panels, 1892, 1st panel, 100 × 200 cm.

Illustration taken from Per aspera ad astra. Schattenfries von K. W. Diefenbach unter Mithilfe seines ehemaligen Schülers Fidus (B. G. Teubner, Leipzig / Berlin, 1914).

Working naked

Heinrich Pudor (1865-1943), the author of the first nudist manifesto, wanted to instate “absolute nudism”. He was a doctor in philosophy but felt angry at the University as an institution and ready to spoil his inherited fortune to impose ideas of his own as a dilettante genius. One only needed to wait a few centuries for the “masses” to rally around nudism.11 For the short term, he recommended “going about naked” (Nacktgehen), not temporarily for air bathing or sports but as a “lifestyle” (Lebensart).12 All protonudists pursued this goal in two ways. On one hand, they took part in many private activities naked, taking care not to be noticed. For example, Pudor wrote naked.13 On the other hand, they pushed for a “fundamental reform of clothing” in public life. Around 1893, Pudor adopted a tunic “simply to hide the nudity forbidden by the police.”14 The Munich-based painter Karl Wilhelm Diefenbach (1851-1913) and his disciples also adopted this stance at the “Humanitas” community in Höllriegelskreuth, active between 1885 and 1892. They worked and made art completely naked while keeping “their light robes” on hand in case of a visit.15 Diefenbach’s word choice reveals that, in his mind, this type of clothing (worn without underwear) was equivalent to total nudity. At the end of June 1889, he noted in his journal: “All this month, through rain and cold, I was still ‘naked’ and without a toothache since I have been starting to wear open sandals.”16

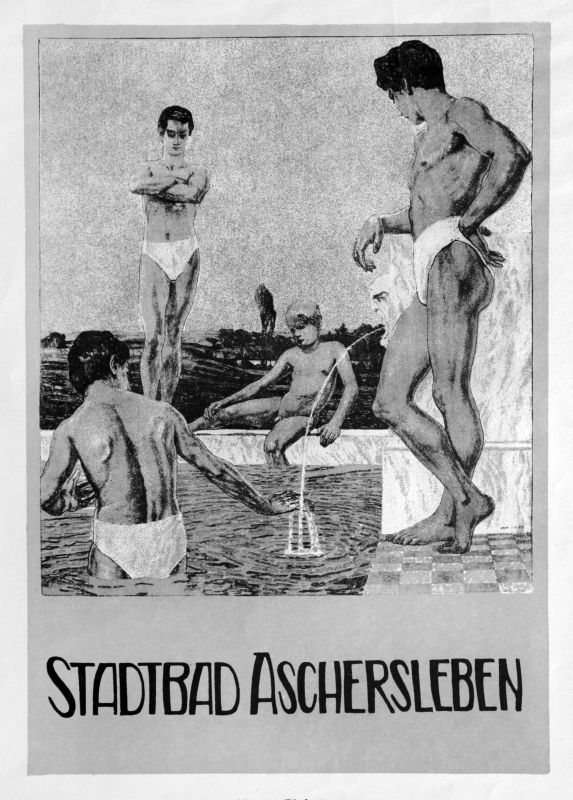

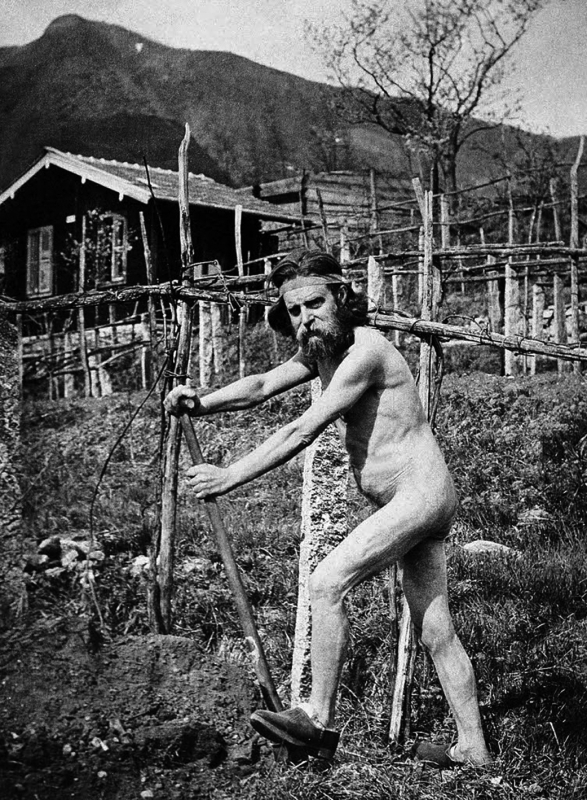

There were parallels at the Monte Verità community, which was active between 1900 and 1919, and integral to the German protonudist movement.17 At the community garden, Joseph Salomonson, who previously had been a trade commissioner, cultivated the land completely naked, guided by the maxim, “sin has clothed us and honor will restore our nudity”.18 This saying of his was inscribed on an illustrated post card, which was edited by the Monte Verità community, and which showed him in a posture evoking traditional representations of the infralapsarian Adam, as a plowman, with that notable difference that he already was bare again, having “cast off the old man / old Adam” in the literal sense. Light clothes were an alternative to this innocent nudity. Ida Hofmann (1864-1926), the principal theorist of Monte Verità, tended to strawberries in the same garden, clothed in “a net dress” which, according to witnesses, barely covered her.19

This line between nudity and semi-nudity disappeared completely with the most radical Monteveritan, Gusto Gräser (1879-1958). Following quarrelling with the other founding members of the community in the winter of 1901/1902, he went to live in a cave in the forest. He passed his time in nature, dressed in a crude self-made tunic. Taking pretext from his name – literally “grasses” – he would offer blades of grass to visitors; a little reference to Walt Whitman. Years later, when he was on trial, a reporter wrote about his “herbaceous” personality which evidently was formed on the third day of Creation along with vegetation and “seed-bearing” plants (Gen. 1: 11-12).20 This well-intended joke had a dimension of truth, not only in terms of Gräser’s imagined identity, but also regarding the theories of other protonudists like Pudor.

Naked at the dawn of the world

By their habitus and way of (un)dressing, permanent nudists most often imitated the sublime surperhumanity of prophets, saints, and angels. But in theoretical elaborations, themes of regression to the “subhuman” were also surprisingly common – regression, in terms of civilization or evolution, to animal or vegetal states. Pudor payed tribute to Diogenes the Cynic,21 who was known for his feral, “doggish,” shamelessness. Pudor recommended living at a slowed pace in winter, eating almost nothing, for lack of (plant-based) food, sleeping a lot, and… lingering on shores in the company of seagulls and marine animals.22 In those few words he set up a scenery of “the dawn of the world” as cold, rather than tropical. He wanted men to regain the thick fur that they were supposed to have lost after adopting clothing.23

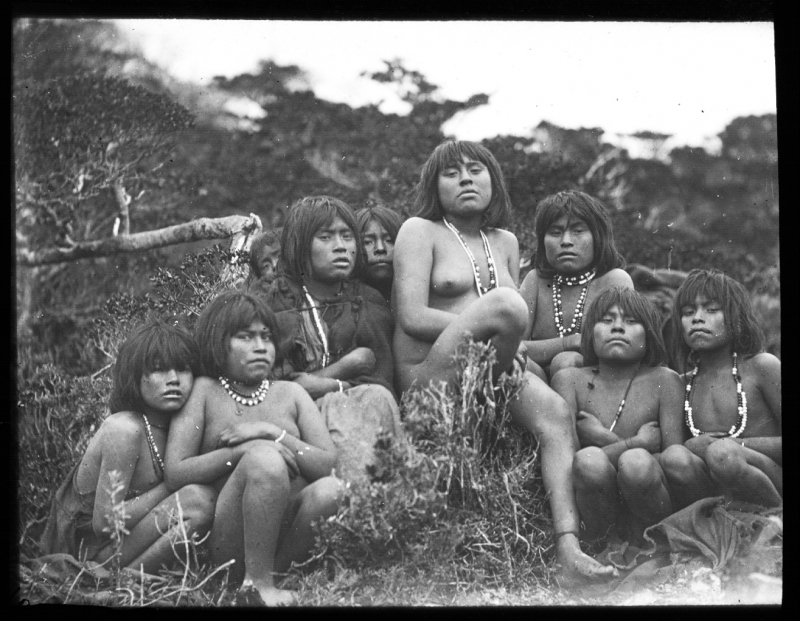

Willhelm Bölsche (1861-1939) had similar ideas. He was a writer and philosopher, a talented popularizer of science, and a friend and admirer of Diefenbach and especially of his disciple Fidus (1868-1948) with whom he was in contact in Friedrichshagen24. He fantasized about cavemen huddled “naked around the red flames of their hearth” while “outside, the ice age glaciers glistened in the starlight and storms raged”.25 In this he saw “the image of paradise according to our current understanding.” He greatly admired Eskimos, the last of the “ice age men,” also naked in their heated huts.26 The protonudists even admired the natives of Tierra del Fuego, thought of as savages since their “discovery” in the 18th century because of their semi-nudity in subantarctic zones.27 They were cited as a model because of their facility for permanent semi-nudity, despite the harshest conditions.28 Still, protonudist references to sublime superhumanity by far outnumber those to this contrasting subhumanity.

Jesus, servant of nakedness; garments trampled

In the protonudist movement of 1885-1909, the figure most often upheld as a model was – as astounding as it may seem – Jesus. His terrestrial existence alone interested the protonudists, believers in monism. In the 18th century, Jesus was interpreted as a prophet of natural religion”. The 19th century added social justice to the mix, and then Buddhist-inspired self-redemption, illustrated principally by Schopenhauer. Under the empire of Kaiser Wilhelm, after 1871, “soft” reformers used Jesus’ name for ends such as the “dignification” of women29 – as well as for permanent nudity or semi-nudity. This state of affairs led the doctor and writer Oskar Panizza (1853-1921) to propose a pathological psychogram which would work simultaneously for Diefenbach, Pudor and Jesus.30 A few years earlier, Friedrich Engels himself launched a “socio-ideological” contextualization of “hole-and-corner reformers” (Winkelreformer) aimed at Diefenbach and his alikes, without identifying them by name – which would have undoubtedly dignified them too much.

The proliferation of these reformers was a minor side-effect of a radical change in progress. They were of the same breed as the exalted, the illuminated, and the imposters pervading the end of the Roman era in the “Christian hall of oddities” – in other words, the Gnostic sectarians.31 Engels and Panizza used very different intellectual tools – Engels with the conceptual apparatus of Marx, and Panizza with the anthropological theories of Lombroso – but the way they write about the protonudists places them firmly on the banks of the Jordan River. Their habitus suggests it but also their teachings.

Joseph Salomonson, former trade commissioner, at the Monte Verità garden.

Illustrated postcard edited by the Monte Verità community, 1907.

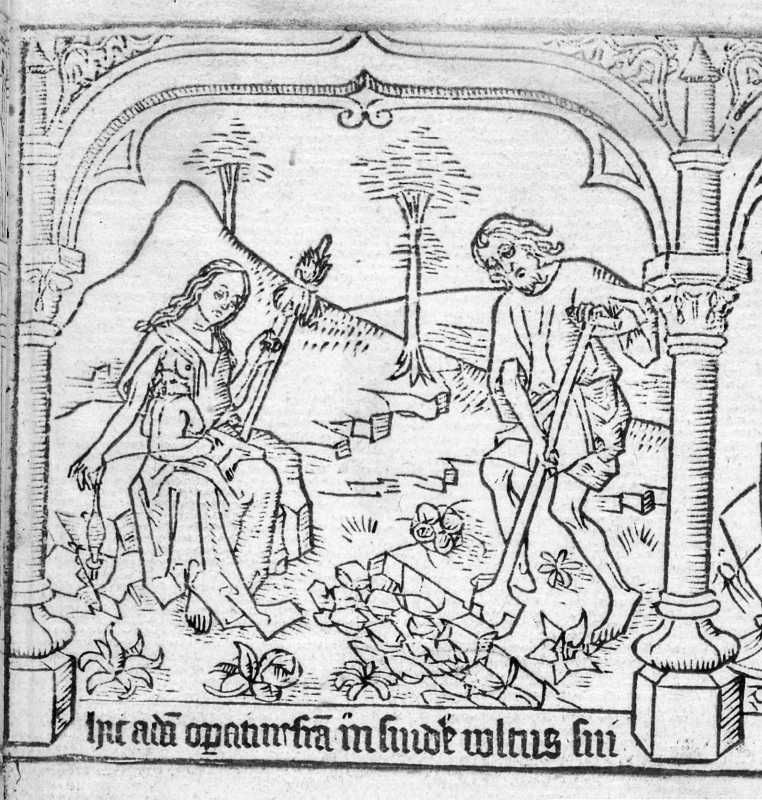

Adam as a plowman.

Woodcut book illustration of the Speculum Humanae Salvationis (Günther Zainer, Augsburg, 1473).

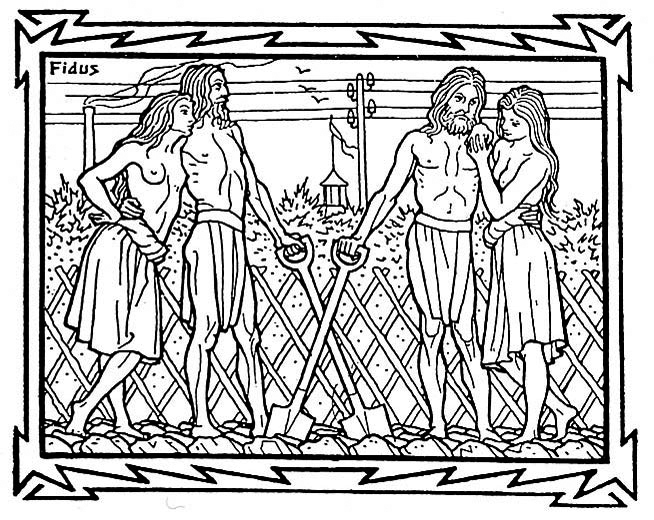

Fidus, No Title.

Illustrated postcard edited by the “Lebensre-form Publishing House” (Verlag Lebensreform), Berlin, ca. 1900.

“Indians of Tierra del Fuego, Isola Grande”

Photography by Edmond Payen, of the French Cape Horn Expedition in 1882-1883. Illustration after a slide produced for public showing. Courtesy by private collector. (original in possession of the “Société de Géographie”).

Diefenbach set up a spiritual “installation” at Höllriegelskreuth. He remade the abandoned quarry and old utility building into his home for seven years. He put a cross bearing the image of “the divine man” of Nazareth next to the access road, fixed large golden letters reading “Humanitas – Menschlichkeit” to the house, and hoisted a white banner reading “Purity, Peace, Love” between the house and the quarry.32 He also painted a number of religious works there, including the “Head of Christ” (Das Haupt Christi, 1887) in numerous variations. Interviewed on the subject in 1892, he confessed that without the “legend of Jesus,” he would never have become Diefenbach “the Second Christ” (Christus der Zweite) and preacher of “humanity” (Menschlichkeit) through his works.33 Significantly, his “exposition hall” in Höllriegelskreuth prominently displayed a copy of the “praying ephebe” from the Berlin antiques collection.34 Still, he cultivated a “picturesque” personal appearance, marking his preference for the Orient (Morgenland).35 At Monte Verità, Ida Hofmann looked to the Essenes for inspiration. This group “from the time of Christ and Pythagoras” was one of the “brotherhoods and communities, founded on noble goals” whose “way of life” (Lebensweise) served as a model.36 According to a Berlin theater critic, Hofmann’s partner Henri Oedenkoven was so “Christlike” that he resembled the actor who portrayed Jesus at the Oberammergau Passion Plays in Upper Bavaria.37 His “personality exuded a noble sweetness”, his glance was “friendly, awake and ardent”, and his long beard and hair completed the picture. The importance of Jesus at Monte Verità – since its founding members weren’t especially religious38 – could be explained by two specific means, in addition to a general circulation of certain “counter-cultural” norms. On one hand, it stemmed from Gusto Gräser, who lived with Diefenbach in Vienna in 1898, after the dispersion of the (first) “Humanitas” community in Höllriegelskreuth. On the other hand, and above all, it stemmed from Adolf Just (1859-1936), a renowned promotor of natural medicine, whose reach extended to the USA, and whom Ida Hofmann admired.39 Adolf Just prescribed a “rigorously natural” way of life that he borrowed from the Essenes, among whom counted Jesus.40 The Essenes went barefoot in white robes41, took daily ritual baths (which Christian baptisms distantly echo)42, and held the key to health and happiness, while preparing themselves for heaven.43 As for Pudor, he told his followers that Heaven could return to earth if men started living like… angels. Clearly, he was familiar with the Gnostic idea of the “return of Jesus Christ” once men adopted “nudo-compatible” chastity.44 This was undoubtedly influenced by the diffusion of the Gospel of the Egyptians throughout the protonudist movement, from fragments transmitted by Clement of Alexandria.45 Pudor didn’t expressly refer to it but his theories retain a clear connection. He wanted men “no longer to indulge in copulating and eating” so that they would stop “dying like flies” and be reintegrated to an earthly paradise,46 just as Jesus preached to Salome in the Gospel of the Egyptians.

When Salome asked how long will death prevail? The Lord said, As long as ye women bear children […]. And Salome said to him. Did I not well then, in not bearing children? And the Lord answered and said, Eat of every herb, but do not eat of that which is bitter. And when Salome asked when the things would be known about which she had inquired, the Lord said, When ye trample on the garment of shame, and when the two shall be one, and the male with the female neither male nor female.47

The naked, the raw, the chaste

The way of life that Pudor recommended essentially in his more “reasonable” writings were far beyond Jesus’ recommendations to Salome, notably regarding sexual abstinence. One could reduce sexual activity to the minimum physiologically possible or only for procreation48. Pudor turned this into a “naturist” triple cure, that, along with the aforementioned nudity and chastity, consisted of a vegetarian or even raw vegetarian diet, based on wild fruits.49 This combination was also present in certain sects of the Gnostic movement during the first centuries of the Christian era, often in even more extreme versions. For example the “grazers” who lived in Syria gathered in “herds” and ate grass while singing the glory of God.50 In Pudor’s “naturist” triptych, nudity, chastity, and vegetarianism form an indissociable whole. The anarchist Erich Mühsam – acquainted with the protonudist movement between Berlin, Munich, and Monte Verità – humorously remarked that “a number of vegetarians hold sexual abstinence among their ethical principles”51 in addition to innocent nudity. He thought “it would be interesting to ask specialists if a vegetarian lifestyle […] results in sterility or impotency, or maybe the propensity towards vegetarianism is present mainly in sexually feeble individuals.”52

In fact, this “naturist” triple cure shows up in the practices of all protonudists, even if its most “striking” element is still nudity. It primarily responded to a desire for sublime superhumanity, but wasn’t completely removed from hygienist arguments. Nudity was the element of the triple cure most closely linked to hygiene. To aerate oneself, even under a light robe, was a sanitary procedure which assured the cleanliness of the body better than regular bathing,53 permitted “the excretion of poison accumulated in the body,”54 and limited subliminal friction of the epidermis which, according to Pudor, killed slowly, like alcohol or tobacco55. It’s not likely that the Monteveritans were seized by these obsessive fears, but Oedenkoven was sufficiently convinced of the utility of “going about naked” that he did it inside as well.56

Karl Wilhelm Diefenbach, When humanity is ripe for nudity: à-la-mode genre painting of tomorrow (Wann die Menschen reif für die Nacktheit: Zukunfts-Sitten-Modebild).

The second title, which appears as linguistically monstrous, can be interpreted in several manners according to the way you hierarchize the four agglutinated nouns. One thing seems sure: Diefenbach operates with the distinction that Nietzsche made between tomorrow and the day after tomorrow.

Illustrated postcard, n.d. (1911?) © Stadtmuseum Hadamar.

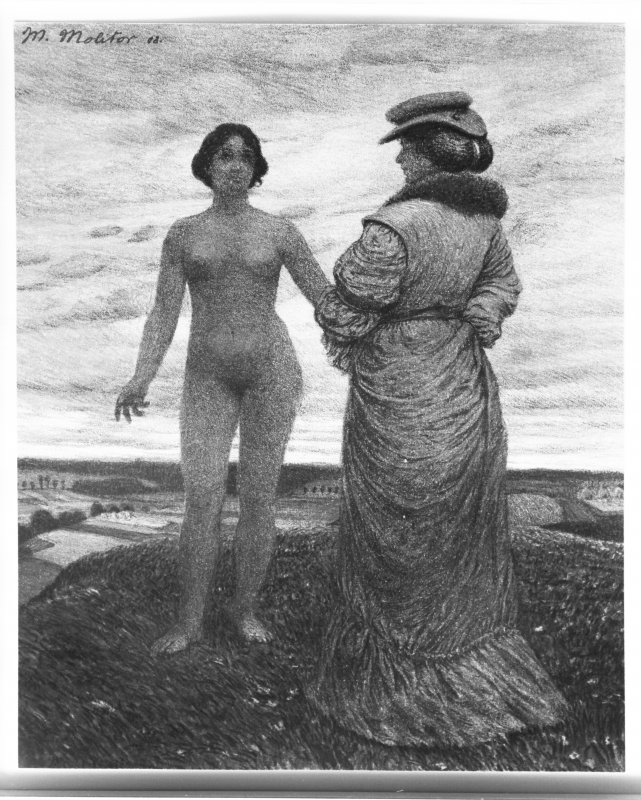

Mathieu Molitor, The Eternal (Die Ewige), 1908, lithograph, 31,5 × 23 cm.

Courtesy by private collector.

Sanitary arguments for permanent nudity didn’t match up (in either quality or quantity) to ethical arguments and/or Gnostic-inspired principles. The same predominance of ethical arguments held true for vegetarianism and chastity as well. Diefenbach firmly believed in the Christian notion of the sin of lust and denounced “vulgar carnal pleasure.”57 Just and Pudor also wanted to limit sexual activity to procreation.58 Pudor and Ida Hofmann both offered a “modern” ethical reinterpretation. Pudor, inspired by Kant, approximated sexual (over)activity with “abuse of oneself.” Ida Hofmann demanded purifying relations between men and women of all manipulation by the former. The “new man” was supposed to “emancipate himself from egocentrism” and respond to “female needs […] while testifying to her his moral purity.”59 Concretely, this requirement necessitated “the strictest self-discipline.”60

The dishonor of clothing

The protonudists subjected clothing to withering criticism. They launched a Nietzschean reversal of values regarding modesty (whose content was actually inspired by Nietzsche). It wasn’t nudity which dishonored men but clothing. Their philosophical process was also tactical one, the best defense being to attack. It was judicious to affirm a priori that enemies of nakedness were the real agents of immorality – all those “policemen of modesty” who, in the name of morality, rooted out nudity in art and on stage, and when possible, attacked it even more ferociously in life. Diefenbach suggested that clothing, subject to the whims of fashion trends, was deceitful and ridiculous. Clothed civilization seemed to him a “simian masquerade” to which he preferred “the paradisiacal dress of the first human couple.”61 He thought this allegory of costumed monkeys so telling that he returned to it two decades later (1911) in a painting titled “When humanity is ripe for nudity: à-la-mode genre painting of tomorrow” (Wann die Menschen reif für die Nacktheit: Zukunfts-Sitten-Modebild).

Pudor also thought clothing led to a “civilization of a menagerie of circus monkeys.”62 And to his eyes the “sartorial lie” masked a flagrant hypocrisy in that, under the pretext of modesty, clothes sexualize and eroticize the parts of the body which they cover. This dialectics of dissimulation and eroticization – to which Nietzsche appealed with gentle humor to explain the variations of ladies’ fashions63 – provoked utter indignation in Pudor. He wrote, “clothes are immodest, they completely destroy mankind’s morality.”64 But the remedy was found.

Ah! I know it too well: what is hidden excites desire even more. Be reassured then: once clothes are abandoned, one might regret a dwindling of sexual relations. At present, your wife excites you because you don’t see the parts of her which are most interesting. If you saw them daily, how could they still excite desire in you? As soon as this happens, moral and sanitary order will be restored […].65

The real intended audience for this speech was perhaps less the hypothetical candidate for nudism than the hypocrite typical of the Christian morality leagues of that time, seeking any pretense for moral outrage. However, Pudor was no less obsessive in his denunciation of “sartorial sin” (Kleidersünde) or the “sin of clothed civilization” (Kleiderkultursünde)66 than the “morality police” in their denunciations of obscenity. According to Pudor, not only did clothing stimulate the imagination, but it stimulated the nerves, to the point of inducing bad habits, particularly in men.67 Thus clothing was a self-sustaining invention: shameful body parts really did become shameful, so were covered by clothes that only aggravated the cycle.

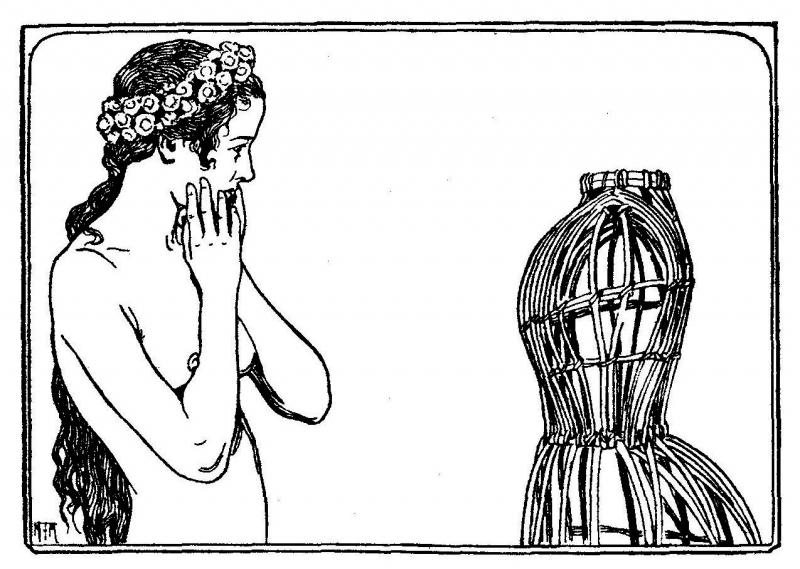

Crime against nature

Clothing, for activists of permanent nudism, became a metaphysical crime. Since man “came naked from the hands of nature”, wearing clothes was an impiety against Nature and the Creator. Diefenbach demanded the abolishment of this accessory “against the dignity of the image of God.”68 In the same vein, Pudor asked all those who believe in Genesis how God could have created man, “the most perfect creature,” in such a “state of deficiency that he has to kill lambs in the meadow, rob them of their wool, and make clothes to cover his children.”69 These clothes which reek of death are themselves “something dead, stuck on man”, “something foreign, that does not belong to man himself”, that “does not fit with man” and that “does not grow with man”.70 It all leads to reification: “the intrinsically naked man” (Nacktmensch) is transformed into a storefront fashion mannequin.71 Trying to reform clothing – which would place more emphasis on it – could only be a temporary solution. The “sins of clothed civilization” would become clear enough that “one day, clothing itself will be a sin.”72 At Monte Verità, Salomonson, the ex-commissioner who wanted to “bury old Adam” while gardening naked, anticipated this happy end to history. Diefenbach and Just, who kept the strongest ties with religion of all protonudists, championed Genesis 2:25, one tacitly and the other explicitly. They used this postulate of the innocent nudity of the original couple to affirm that “living naked is natural and thus just” and so brings joy to God.73

The plant-man

Proponents of permanent nudism all operated with a three-part biblical schema which they wanted to instate, a schema of restitutio ad integrum. In this sense, they had the same path-breaking attitude as the Gnostics, with whom they shared ascetic principles regarding sex, clothing, and food. They were both profoundly alienated from modern civilization, or from all civilization for that matter. Adolf Just went as far as to decry the invention of the printing press and Pudor decried the production of books. This didn’t stop either of them, however, from publishing.74

Nudity or semi-nudity also entailed vulnerability to the world. Aside from gardening, most transformative activities were rejected. Adolf Just cursed Prometheus, who, in giving men fire, opened their path to metallurgy and pottery.75 The predilection for raw vegetarian food – out of sanitary reasons, but mostly ethical ones – showed a desire to revert men to the first link in the food chain, and to avoid transforming products of the earth.

Pudor also upheld a certain ethic of passivity. He formed a unique anthropology where man was not at the summit of the animal kingdom but… of the plant kingdom. He writes, “man must learn to consider himself a plant – and so he will grow anew.”76 This concept of “plant-man” justifies the “naturist” triple cure. Plants die if they’re deprived of light and of gaseous exchanges with the atmosphere. So permanent nudity was recommended, along with reduced sexuality and diet, to approach men as closely as possible with the plant kingdom. Food had to privilege ethereal elements. Fruits were also prescribed since they contain (or even consist of) seeds, which propagate their species. Sexuality also had to privilege ethereal exchanges that were non-copulatory. It’s true that there were exceptions, notably regarding procreation. Fidus, who shared the ideal of “plant love” (pflanzliche Liebe)77 drew several illustrations on this theme. He also drew plant-men and especially plant-women, who lent themselves even better to anti-Promethean concepts, of symbiosis with the natural world.

The cultivated bourgeois revolting against the established order

Protonudists often rejected the masculine order, the patriarchy, and the father figure. Pudor and Oedenkoven consciously adopted the behavior of prodigal sons. Gräser refused to accomplish his military service for the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Pudor, in the German Empire, procured the shortened service, reserved for the better educated, but was soon discharged for rheumatism… and was filled with hate for the army, which he found inhumane and increasingly irrelevant in a time of lasting peace, if not perpetual peace.78 Pudor also joined Ida Hofmann in her feminist struggle and shared her reverence for Ibsen’s A Doll’s House.79

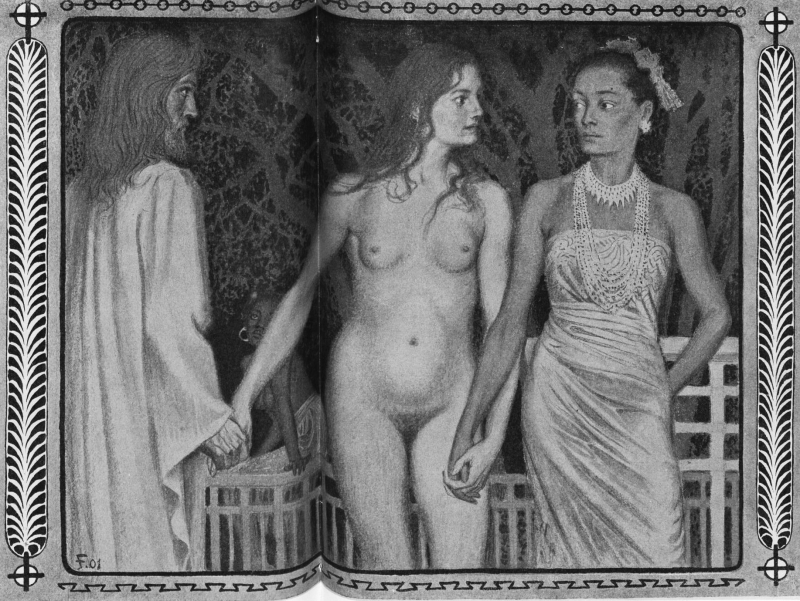

Diefenbach was the exception in that regard. He stayed part of the patriarchy, granting himself the role of master over the women around him. Despite his pretension of avoiding the world of flesh, he engaged in multiple affaires with these women and commanded them in all sorts of tasks.80 In 1904, Fidus – who was Diefenbach’s loyal companion (hence his name) from 1887 to 1889 at Höllriegelskreuth – drew an illuminating illustration of this paradox. We see a protonudist, dressed like a desert hermit, drawing a naked woman towards himself. She evidently has undergone her nudist “moulting” – her “conversion,” according to the illustration’s title, by which she will distance herself from the world of so called dolls. This “conversion” however hints at the erotic temptation exuded by the man – by a curious inversion of the traditional theme of the temptation of Saint Anthony or of the recluse monk.

Fidus, Conversion (Bekehrung).

Illustration taken from Die Jugend, vol. 9 [1904], p. 956/957 [no. from 14/11/1904]

But Diefenbach satisfied the standards of protonudists in all other traits and beliefs. A main one was the refusal to let oneself be subdued to any command, especially of the state. In an era where the “civilization of the employee” was developing,81 this attitude appears frequently in individuals of the intellectual classes. They preferred to be creatives and promoters of ideas, living in precarious material situations, rather than in (petit-)bourgeois lifestyles. The theorists and practitioners mentioned were all adept at self-publishing in order to diffuse their ideas. They were entrepreneurs in their own right, promoting various projects (relating to food, housing, and artworks). Their paths through life were chaotic and most had trouble establishing successful plans in the medium or long term. Adolf Just seems at first to be an exception because of the successful “naturist health retreat” called “Jungborn” (Fountain of Youth) which he opened in 1896. But, on closer examination, this success is due mainly to his younger brother, Rudolf (1877-1948). Adolf merely maintained the adjacent orchard…

Finally, to end this typology of nudist activists, we must note that the “naturist” cure which they preached was more broadly inscribed in the German Lebensreform of 1890-1914. This heterogeneous movement saw certain representatives of the “cultured bourgeoisie” (Bildungsbürgertum) attempt to transform a blocked society by peaceful means. They had grown restless under the Wilhelmine and Habsburg Empires and were bitter about being relegated behind other elites – members of the imperial court, feudal land-owners, ennobled industrials and bankers, senior officers – for whom they had only contempt. They attempted to transform individual lives for a soft revolution of society. This typically Germanic mutation of the ideals of 184882 (at a two generation remove) was evident in Pudor but also in a diluted form in Diefenbach and Ida Hofmann, or in Fidus’ first partner Amalie Reich (1862-1946) the daughter of a “historic” Forty-Eighter, and herself “life reformer” in several domains.83

The nudist tailor and the diffusion of nudism

Protonudist theorists and practitioners had some impact on German nudism and, by association, global nudism. Pudor’s argumentation (following Nietzsche) that clothes sexualize and eroticize, was often reiterated in nudist discourse. Diefenbach entered the history of nudism as the first declared practitioner to be put on trial (1888). Pudor entered history as the author of the first known manifesto (1893). Monte Verità entered history as one of the first places in the world where it was practiced, since 1900. Nevertheless, the ideal of permanent nudity or semi-nudity, that was accompanied by sexual abstinence, and by raw diet vegetarianism and even periods of complete fast, condemned its proponents to experimental insiderness. Significantly, Pudor disavowed the “nudist movement” as it developed from 1909 onwards, on account of moral betrayal.

The founder of the first modern nudist association, Wilhelm Kästner (who died in 1918), was a ladies’ tailor with a practical approach. The nudism that he advocated – through an ephemeral journal, Der Lichtfreund (The friend of light), which was founded in 1908 and disappeared after six issues – sufficed in itself, justified by physical and mental hygiene. Nudist “Koedukation” was his guiding phrase – a “catching up” for a generation of young adults raised in excessive prudishness.84 He shared the conviction of certain education reformers of his time that insufficient knowledge of the opposite sex in its “overt” characteristics since childhood generally leads to sexual perversion and mutual disrespect among adults.85 It can be assumed that questions of bodily health were also part of his profession as a tailor. The predominant discussion at the beginning of the 20th century concerned the necessity of adapting clothing to valorize the natural shapes of men and women – especially of women, who had been particularly repressed. The tailor would have been part of this discussion.

He officially created the Freya-Bund in September 1909 at Friedrichshagen, a village next to Berlin (confirming its newly acquired reputation for anticonformism).86 The name Freya-Bund, meaning the Freya Association, referred to the Germanic god of love and fertility. Kästner intended to attract the feminine public. Members met in an orchard87 and later a park in Lankwitz, another village close to Berlin that the French writer Marguerite Le Fur raved about in 1912.88 Her tale of her “[nudist] reeducation” in Le Mercure de France praised the beauty of the “sports park” crossed by a brook, the quality of the equipment, including “changing cabins”, and especially the freedom offered by recreational nudism. Therein she saw a rebirth of the Spartan ideal where “completely naked young men and girls assembled to engage in open air games and gymnastics without good morals having to suffer”. In 1913, the Freya-Bund again relocated and changed names. It became the Monboddo-Bund, taking its name from an 18th century Scottish judge who also engaged in philosophical enquiry and… the promotion of air bathing.89 The new location was Mahlsdorf, another village close to Berlin, where a park was at disposal, pleasantly named “Come see” (Kiekmal).90 The association didn’t get closer to the center of Berlin but had the advantage of owning its nudist park instead of being merely a tenant. After the First World War, a former collaborator of Kästner, named Fedor Fuchs, promoted the most “open” type of “Free Body Culture” (FKK) which was to be observed on the nudist scene of Berlin under the Weimar Republic.91

In the evolution towards recreational nudism – “weekend nudism” one could call it – traces of the prophets of permanent nudism are tenuous. But some still remain. It was Pudor who pulled the symbolic figurehead Monboddo from obscurity.92 Kästner then adopted the name for his second association (1913) and edited a small text about him.93 He didn’t reference Pudor – who admittedly had taken an anti-Semitic turn since 1912 – but the tailor was evidently influenced.94 Fedor Fuchs, too, honored the prophets of permanent nudism by proposing that nudity should not be designated by the usual term (Nacktheit) but by the term “natural clothing” (Naturkleid).95 This recommendation was not motivated by Victorian style lexical prudishness but by the idea that man should “ideally” live naked, with only his skin as clothing, considering all other costumes as foreign. This term was not widely embraced, but the phrase “clothing of light” – of the same philosophical tenor, with an added whiff of mysticism – gained widespread usage.96 Finally, according to Giraudoux, who explored the Berlin nudist scene in 1930, the attitudes of Weimar nudists still reverberated with the paradisiacal inspiration dear to the prophets of permanent nudism:

Each race naturally reshapes one of the idyllic images of humanity. […] In Germany, and especially amidst [the] lively lakes and forests [of Berlin], it’s the tale of Adam and Eve. They’re both there in all their forms, in all their real forms – there’s not one fold of skin, pad of hair, whether loose, frizzy, or curly, peach colored knee, or callused elbow drawn on the primitive couple by Cranach, Dürer, or Böcklin which you wouldn’t find a hundred times over on these beaches.97

Josef Bayer, No title.

Photography published under the rubrique “From the FKK movement” in the biweekly Figaro. Halbmonatsschrift für Geist- und Körperkultur, vol. 6 [1929], p. 186 [no. 5].

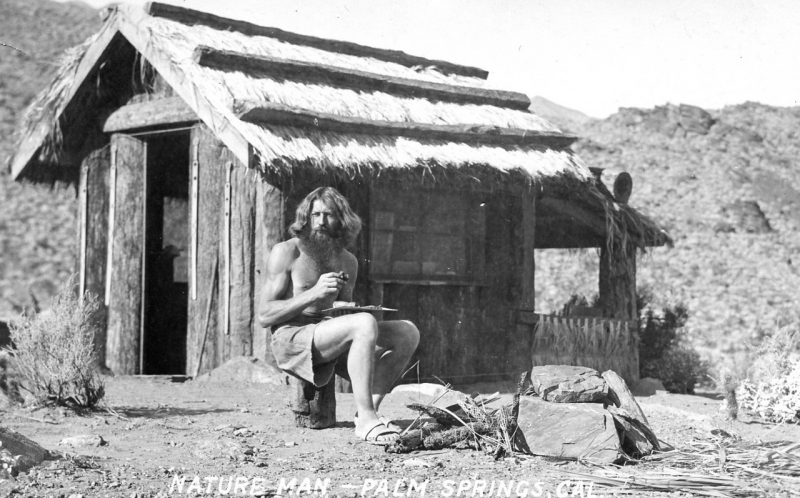

“Nature Man”, William Pester before his cabin, Palm Canyon, California, 1917.

William Pester, known as “the Hermit of Palm Springs”, left the German Empire in 1906 in order to avoid military service. He settled in Palm Canyon, ca. 200 km east of Los Angeles. He used to sell self-designed postcards by the road, featuring Lebensreform topics as vegetarianism and nudism. He inspired George Alexander Aberle a.k.a. eden ahbez to his song “Nature Boy”, which helped to spread this type of counter-culture in the USA from the 1940s.

© Stephen H. Willard.