On July 17, 1919, Alta Johnson, “a very pretty and young matron”1 visited the beach in Santa Monica, a seaside town in the Los Angeles metropolitan region, for a picnic with her husband, son and a friend. Realizing they were out of bread, she slipped a short bathrobe over her swimsuit and headed along the city’s streets. This story would certainly have been unnewsworthy, had it not ended with Alta Johnson’s arrest by a particularly zealous police officer, Ben Carrillo, on the charge that her knee-length bathrobe revealed her legs. A municipal ordinance stipulated that bathers wear appropriate city clothing, covering their entire bodies, when crossing the unmarked barrier separating sand from pavement. The ordinance had inspired much debate in the years leading up to Johnson’s arrest, with enforcement depending on the inclinations of local police officers. Following legal advice, Alta Johnson threatened the city with a lawsuit. Indeed, as the local newspaper explained, “scores of pretty girls walk[ed] on the promenade and [went] back and forth to the apartment houses without any covering at all over their bathing suits.”2 Since the rules were constantly broken, argued Alta Johnson’s lawyers, they had lost all meaning. The municipality rescinded its decision and apologized to Johnson, thus ending the controversy, and in the years that followed, bathers were, for the most part, left free to wear their bathing suits on the city streets.

Alta Johnson’s story is one in a long list of bather arrests that took place near the beaches of Los Angeles between 1915 and 1919. The prohibition of bathing suits in the city covered Santa Monica and Venice, both independent from the city but integrated in its metropolitan region.3 While some considered these laws excessive, others believed they were essential to preserve proper morals and the decency of women.4 Interestingly, these ordinances provoked far more discussion than the stipulations concerning the proper length and shape of bathing suits. By chronicling what Anne-Marie Sohn termed the “erosion of modesty”5 on Western beaches in the 19th and 20th centuries, historians have retraced the steps from the unrevealing bathing dress with swimming cap and bloomers, worn by women in the late 19th century, to the famous bikini, invented in 1946.6 But this fascination for the progressive shrinking of the female bathing suit has resulted in an overly schematic and teleological narrative, which obscures other developments that, although less spectacular, have had a profound impact on the evolution of public bodily display in the 20th century.7 This article focuses on the hidden history of the ordinances that spatially circumscribed bathing suits to the beach or, even more restrictively, to the ocean. As police archives in Santa Monica and Los Angeles are not accessible – the first was destroyed, the second is not open to the public – this article relies mostly on the local newspapers that almost systematically reported these arrests.8

The controversy over the wearing of bathing suits on city streets is not dissimilar to contemporary debates regarding other items of clothing and the spatial context in which they are appropriate. From municipal orders established in small seaside towns in the south of France to prevent tourists walking around in their bathing suits, to the banning of shorts and naked shoulders in Italian churches, plus of course the heated debates over the public wearing of veils in France, controversies about the presence or absence of a specific piece of clothing abound, especially in spatial contexts considered sacred or secular. As Nicole Pellegrin argues, these garments signify “the social division of time and space.”9 Because they symbolize differing spaces and times of the year or one’s life, the meaning of items of clothing shifts depending on where and when they are worn. A spatial history of the bathing suit must thus take into account the spaces where it is deemed appropriate, and their boundaries, as well as the manner in which female and male bathers, in their daily habits, challenged these conventions. In this article I consider the spatial restrictions imposed on bathers within an urban context. In Los Angeles, a city that witnessed spectacular demographic growth at the start of the 20th century, alongside intensive agriculture development, real estate speculation and the emergence of Hollywood, the beach was literally in the city. Although originally founded inland, Los Angeles had absorbed its shoreline at the beginning of the century, meaning Angelinos could spend their morning working in a busy downtown office and their afternoon sunbathing on one of the metropolis’ vast, sandy beaches, all easily accessible by car or tramway.

The local authorities were well aware that they could not regulate the beaches like any other urban spaces. As the beach allowed semi-nudity and a partial relinquishing of decency, it represented a potentially dangerous place that required monitoring to prevent the relaxed seashore atmosphere from “contaminating” behaviors and moral standards in the city. But rather than imposing strict regulations on the types of bathing wear permissible – which risked scaring bathers away to competing resorts – municipal authorities in Venice and Santa Monica chose to focus their efforts on maintaining a frontier between the beach and the city. However, a distinction between the two spaces proved difficult to impose. Male and female bathers continually challenged the frontier between the city and the beach, eventually influencing what was considered proper city clothing. Unlike existing narratives on the many “beach battles”10 of that era, which almost exclusively focus on women, the East Coast of the United States, and controversies over the proper length and shape of bathing suits, this article takes both male and female bathers into account and highlights the role of Southern California in the emergence of a new seaside etiquette. Above all, by adopting a micro-local scale, I bring the invisible frontiers that crisscross urban space to light and the way city-dwellers, in their daily movements, caused these frontiers to move. Finally, this article contributes to the history of beaches in the 20th century which, in comparison with the well-studied 18th and 19th centuries, has been relatively neglected by historians.11

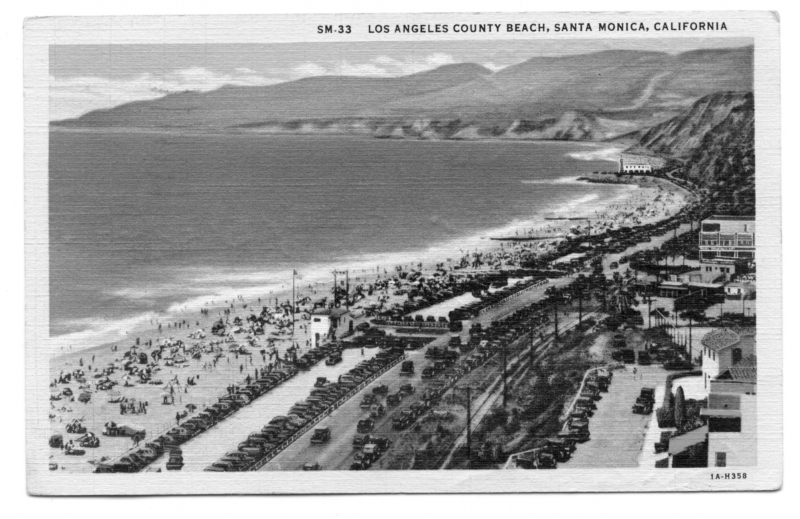

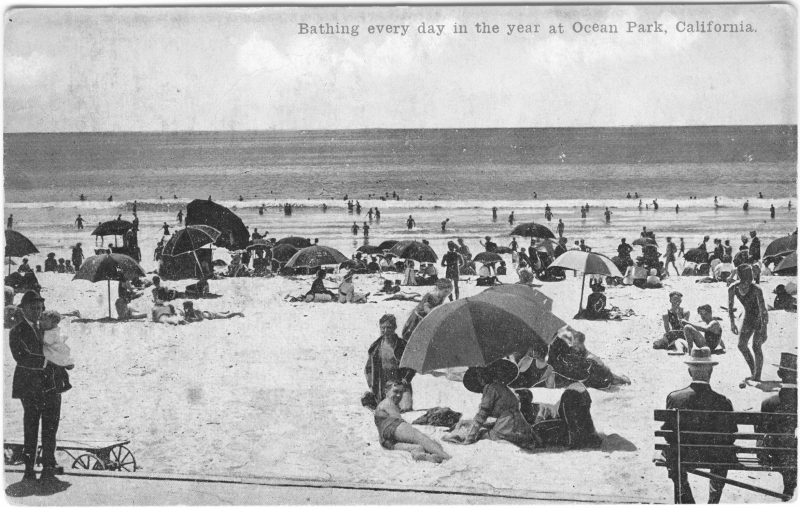

Postcard of Santa Monica beach. In the 1910s and 1920s, beaches in the Los Angeles region were easily accessible by car — as evidenced by the many parking spaces available for visitors — or by tram.

Private collection.

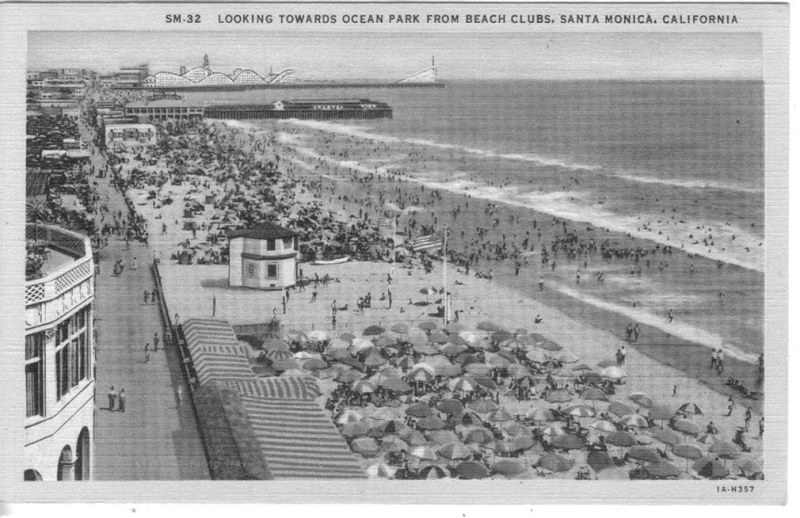

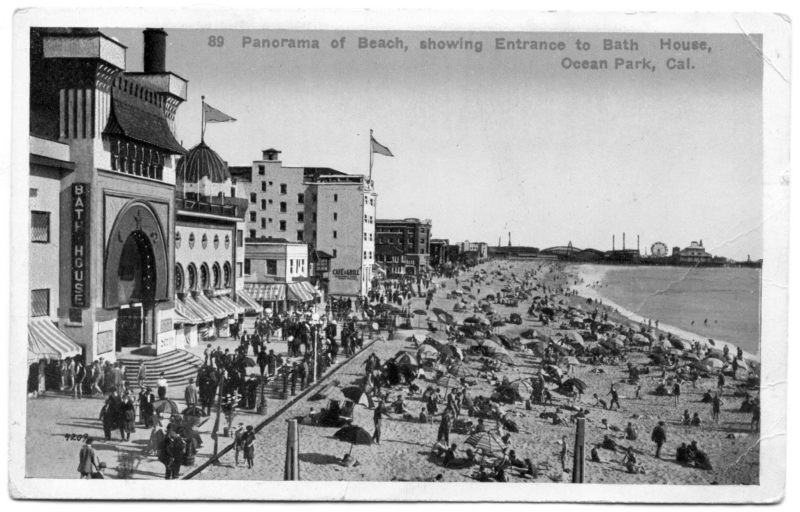

Postcard of Ocean Park beach in Santa Monica. In the background stands one of several amusement park piers that existed along the shore-line.

Private collection

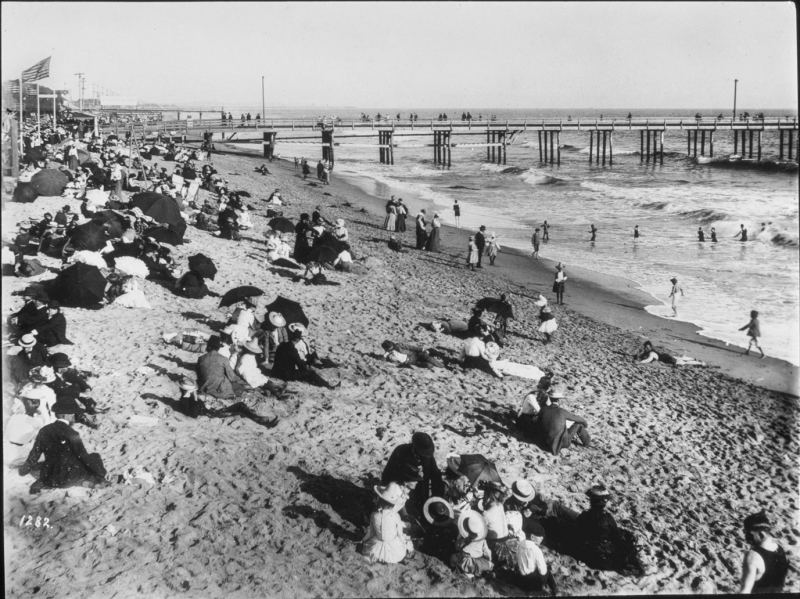

Bathers at Santa Monica beach in 1910. In the early 20th century, women wore large wool dresses and stockings to go swimming; some even wore a swimming cap to cover their hair. Men wore outfits that covered them up from their shoulders down to their knees.

Courtesy of the Santa Monica Public Library Image Archives.

Santa Monica beach in 1908. At the beginning of the 20th century, most visitors remained in their city clothes while on the beach.

Courtesy of the Santa Monica Public Library Image Archives.

The origins of the controversy

At the end of the 19th century, several beach resorts were created along the Los Angeles shoreline complete with boardwalks, indoor pools, hotels, amusements parks and bathhouses. This was a lot later than similar resorts established in Europe or on the East Coast during the 18th and 19th centuries, therefore Los Angeles’s beach towns were developed according to a leisure ethos, devoid of earlier associations with health and hygiene. This meant that in Southern California, for instance, bathing was never a sexually segregated activity. From the very beginning, the Los Angeles shoreline established itself as a mixed-gender leisure space where bathers could enjoy the sensory and visual pleasures typically associated with the seaside. However, like everywhere else in the US, bathing outfits were regulated by modesty laws. In the 1910s, most beach resorts stipulated the precise length and shape of swimsuits. Both women and men were supposed to wear knee-length outfits that also covered their shoulders. In addition, women should wear full-skirted dresses covering their hips and thighs, and on some beaches a swimming cap and stockings were recommended.12 In other cities, however, such as Santa Monica, laws were deemed unnecessary and bathers were left to their own judgment and sense of decency.13 In other words, bathing suit etiquette was enforced either formally or informally through collective pressure. Most importantly, the prescribed outfits were designed exclusively for swimming. In early 20th century photographs of the Los Angeles shoreline, visitors on the beach remain fully dressed. Evidently, as soon as a bather exited the ocean they were expected to head straight to the bathhouse, shower, and change into their city clothes. This expectation was not always met: some bathers would attempt to discreetly change their clothing on the beach, running the risk of being arrested.14 However, the beach, and to a greater extent, its surroundings, remained spaces where city clothing was expected.

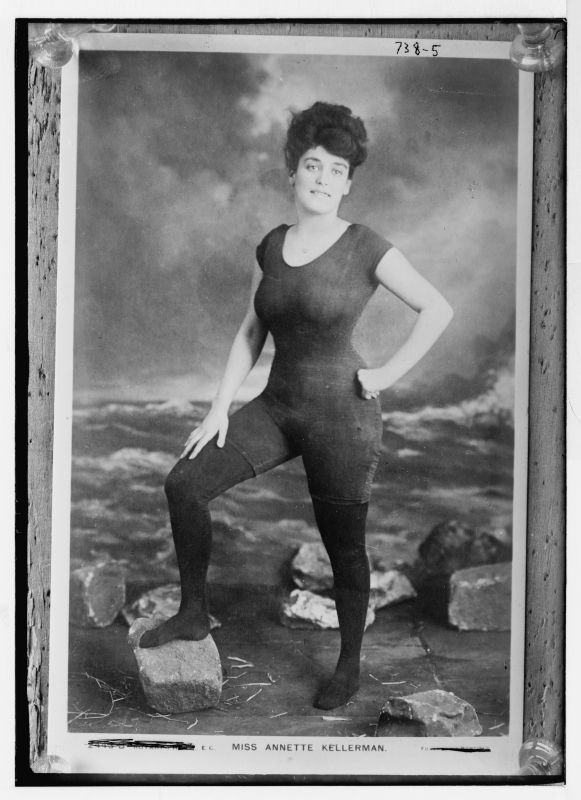

Around the mid-1910s, this situation changed abruptly due to the combination of several factors. Firstly, the one-piece bathing suit for women – a tightly-fitting outfit of dark fabric, which left the legs bare and enabled the bather to swim far more easily than a dress and stockings – made a notable appearance. In 1907, Australian swimmer Annette Kellerman was arrested for indecency in such an outfit on Revere Beach, a resort near Boston.15 Secondly, sunbathing and tanning became popular among the American middle and upper-classes during the 1910s in conjunction with the development of tourism in the tropics and the success of outdoor sports.16 Lounging on the sand after swimming, and presenting one’s body to rays of sunlight, became an increasingly common hobby. Finally, the Los Angeles beach communities experienced rapid growth during that period, transforming from small resorts into full-fledged year-round residential cities. Many Angelinos chose to move to the coast and commute between the ocean and downtown. These newly-arrived residents formed the basis of a small local elite – mainly composed of businessmen involved in tourism and city affairs, and religious leaders – that established itself as guardian of the city’s respectability.

Annette Kellerman in her famous one-piece bathing suit (1919). She was wearing a similar swimsuit when she was arrested for indecency on Revere Beach, a resort located near Boston, in 1907.

George Grantham Bain Collection, Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, [LC-B2-738-5].

The first arrests

It was in this context that the controversy over the wearing of bathing suits on city streets emerged. A growing number of female bathers wearing the above-mentioned one-piece swimsuits could be seen walking along the beach, playing ball or lying on the sand. Worse, some male and female bathers dared to venture out into the adjacent city streets in search of something to eat or drink, or simply to go home, clad in their bathing suits. This behavior, although commonplace today, represented a rupture in a society where the body was never exposed in public. Hostile reactions, particularly from local religious au thorities and upper-class women’s clubs, multiplied, and arrests began in earnest. The public were so confused about the situation that in 1916, Santa Monica’s Police Judge explained himself in the local newspaper: “No one has been arrested or tried or will be because of the kind of bathing suit worn while in the surf or on the ocean front sand.” The only bathing suit ordinance that existed, he continued, concerned the necessity of wearing “an outer garment covering over the bathing suit while going through the streets.”17 What happened on the beach was not important, as long as people respected the law in the city.

Elsa Devienne Controversy in Los Angeles Around the same time, Venice’s elite, especially local religious leaders, were mobilizing to enforce a similar ordinance. The first arrests took place in 1914, and ignited such protests the police were temporarily compelled to stop enforcing the law. By the following year, however, police claimed the general atmosphere had changed, when several East Coast tourists, “unaccustomed to seeing people on the streets clad only in bathing suits or lounging about on the beach,”18 complained to the authorities. Indeed, California beaches had a reputation for tolerating lighter clothing than their East Coast equivalents; in the 1916 Sears, Roebuck & Co catalogue, the most daring women’s swimsuits were advertised as “California Style.”19 Venice authorities believed maintaining the town’s respectability could be an asset, attracting tourists who valued certain levels of decency. The municipality therefore opted to forbid bathing suits not only from the city, but also part of the beach, stipulating that bathers must “neither lounge nor go east of a point 20 feet east of high tide line” in their swimsuits.20 In other words, they had to put their clothes back on or cover themselves with a bathrobe as soon as they had finished swimming. In Venice, as in Santa Monica, the ultimate goal was to create an impermeable barrier between the city, where social conventions must be respected, and the beach, where authorities had to be more flexible if they wished to attract visitors. But by imposing urban attire even on the sand, Venice attempted to distinguish itself from its rival and neighbor, Santa Monica, and thus win the battle of respectability.

A controversial ordinance at the local level

These decisions were not taken lightly; in the multiplying and competing beach resorts, enforcement of these ordinances could have a major economic impact. Satisfying everyone, however, proved difficult. Los Angeles’ public beaches were frequented by a diverse range of people including wealthy tourists from Boston and New York alongside local factory workers. Moreover, while some East Coast tourists frowned upon revealing bathing suits, others had come to California hoping to catch a glimpse of the famous Bathing Beauties: young, slim actresses who appeared in revealing bathing suits in the burlesque comedies of director Mack Sennett between 1915 and 1929.21 Local businessmen were well aware that the seaside imaginary circulated by Hollywood and tourist brochures had a profound impact on visitors’ perceptions of the shores. In Santa Monica, after several arrests took place in 1916, the owner of a local bathhouse remarked that it was not prudent to send young bathers to jail because they were wearing fashionable bathing suits in the street, while the city itself was circulating brochures portraying a young woman wearing a similarly suggestive outfit.22

Many businessmen supported flexibility in bathing suit regulation. For instance, the Ocean Park bathhouse owner in Venice, believed police were interpreting the law too “literally” when arresting his clients buying refreshments in the store across from the beach in their bathing suits.23 Frank E. Bundy, one of Santa Monica’s most prominent businessmen, worried that reports of the arrests in local newspapers would earn the city a bad reputation among tourists.24 In contrast, local religious leaders were in favor of strict enforcement of the law. Reverend C. Sidney Maddox, pastor of the First Baptist church in Santa Monica, fervently supported the campaign of arrests during the summer of 1916 and organized public conferences on the subject.25 The local elite were therefore bitterly divided over the ordinance and whether systematic enforcement was required.

The impossible enforcement of the ordinance

From a practical point of view, the ordinance was also difficult to enforce. Authorities faced multiple conundrums: should the boardwalk and piers be considered part of the beach or the city? What about tramways and cars? The ordinance in Santa Monica did not specify the exact barrier point beyond which bathing suits were banned. Most of the time, these questions were handled on a case-by-case basis when public complaints were made to the police. In July 1916, for instance, a 22-year-old woman was arrested while riding along the beach on an electric tram car, for “causing considerable excitement along the front and greatly shocking those who were out to enjoy a quiet walk along the water.”26 The young woman was released without paying a fine, but did have to undergo a reprimand from “the police matron,” a female police officer. Cars presented a particular problem as it was unclear whether the police should consider them public or private spaces. By the end of the 1910s, driving to the beach in one’s bathing suit to avoid bathhouse fees was becoming increasingly common. Most Angelinos saw their vehicles as an extension of private space. A 1924 car accident apparently resolved the issue: the three young women involved, all wearing bathing suits, were allowed to leave the scene without being fined or taken to jail.27 Despite this incident, police appear to have been more determined to enforce the law when women were involved. In July 1916, a 16-year-old man was reprimanded for having walked into a store in his bathing suit.28 One month later, a young woman from San Francisco was arrested and taken to the police station for buying groceries over half a mile from the beach while wearing only a short coat over “a fetching bathing suit of the latest style and cut.”29

In parallel with these decisions, municipal authorities took measures to create a clear border between beach and city. In 1916, the Santa Monica police erected signs along the shoreline indicating it was forbidden to walk beyond that point while wearing a bathing suit.30 The initiative proved insufficient, however, and the following year a journalist remarked that the boundary, “not indicated by a rope”, was “just as easy to cross as the equator.”31 This statement indicates that many bathers were not conscious of crossing the frontier and that even if they knew of the ordinance, could easily commit the offence by accident. The absence of visual markers that would have clearly demarcated the beach from the city, such as ropes or other barriers, made it difficult for such a law to be enforced. In a similar manner, informal segregation laws on Chicago’s beaches were famously broken in 1919 when a raft built by a group of African-American children drifted into the white section of the shore. The ensuing protests by white bathers and eventual brawl sparked race riots across the city.32 The material circumstances and, in this case, the ecological conditions that governed coastal currents, prevented bathers from obeying the law.

Equipment and staffing issues also compromised enforcement of the ordinance. In early summer in 1917, Venice’s Police Chief claimed there were “not enough police in the city to watch all the bathers.” Moreover, the police were not equipped to go on the beach or even in the water: “What chance would a policeman have with a bather who took to the water after a chase through the streets?” he lamented in the local paper.33 In theory, the police could ask the lifeguards for help, but many of these disliked the bathing ordinance. Interviewed by a local newspaper in 1917, lifeguard Charlie Kirby explained his reluctance to enforce the law: he feared that if he did he “might be told to wear an overcoat when on duty.”34 As law-breakers themselves, since they wore bathing suits on the beach and its surroundings, lifeguards opposed strict enforcement of the law.

The many problems municipalities encountered when enforcing the ordinance reflect the difficult task of policing urban beaches. A lack of uniformity in municipal laws along the coastline, the absence of a police force specifically assigned to the beach, and the elusiveness of the frontier between sand and pavement are just some of the factors that explain why the seashore benefited from a different, slightly more flexible, legal regime than the city. Near-constant debates on the manner in which the ordinance should be enforced also indicate that transgressions were recurrent, possibly even daily, occurrences.

Ocean Park beach in Santa Monica, 1915. While some visitors remain in their city clothes, most people present on the beach now wear bathing suits. It is difficult, however, to locate the exact border between the beach and the city: does the wooden boardwalk (pictured in the foreground) belong to the beach or the city?

Private collection

The transformation of the beach into a space of idleness and body display

Offending bathers were not all treated with the same severity. In 1917, when some wealthy Santa Monica residents complained that wearing a high-quality bathrobe over a dripping bathing suit could damage the material, Police Judge King tried to soothe tensions by prudently replying that only those persons “who loiter[ed] about the streets in their bathing suits and evidently [we]re not either hurrying to their homes or hurrying to the beach should be arrested.”35 Police officers were thus encouraged to take into account the behavior and social standing of bathers before making an arrest. King went even further and clarified that the goal of the ordinance was, above all, to “prevent vulgar display of the persons of bathers on the streets.”36 In particular, he denounced those “girls who like to put on bathing suits and lie around on the sand, but who never go near the water” although he also immediately added that some “men, too” were at fault, and they “ought to be ashamed of themselves to be so immodest.”37 In the eyes of the police, then, the ordinance was less about preventing the wearing of bathing suits in the city than regulating bathers’ intention when they went out in such an outfit. If it was just a matter of local homeowners saving time, the police ought to be understanding, but if the bather deliberately paraded their body in the street an arrest was justified. Evidently, what truly lay at the heart of the controversy was the voluntary and deliberate exhibition of a semi-naked body in public space.

These discourses also signify another major revolution in the history of the beach during the 20th century: its transformation into a space where horizontal immobility and idleness were authorized. This reflected a broader shift in the dominant attitudes of American society to leisure. As historian Cindy Aron explains, upper and middle-class Americans in the 19th century used their vacations and leisure in the pursuit of self-improvement, often at chautauquas, resorts where middle-class men and women attended lectures and meetings on a diverse range of subjects, from religion to the state of prisons.38 At the turn of the 20th century, the emergence and success of new commercial amusements such as movie theaters, dance halls, and amusement parks contributed to the development of a new mass culture, which challenged prevailing notions of leisure as productive time and celebrated the fleeting sensory pleasures experienced when riding a roller coaster or watching a movie.39 The tensions caused by this new mass culture were particularly apparent in discourses on seaside pleasures: for the most zealous partisans of the Victorian order, bathers broke the law not only when wearing bathing suits in the city’s streets but also when they remained in such an outfit despite having no intention of swimming. Religious leaders denounced bathers who paraded along the beach in their bathing suits as “disporter[s], sand lounger[s], and rotten apple[s],”40 who “lack[ed] restraint”41 and belied the hygienic and health justifications of seaside bathing. While the new sensibilities that presided over the “invention of the beach”42 emerged in the 19th century, as Alain Corbin demonstrated in The Lure of Sea, another major transformation in the history of seaside leisure took place in the early 20th century when the beach gained acceptance as a space where immobility, idleness, and bodily display were authorized. The modern beach – where “disporters, sand loungers and rotten apples” may flaunt their semi-naked bodies – has nothing in common with that of the end of the 19th century, when most visitors sat genteelly on the sand in their dark city clothes.

The end of the controversy

By the end of the 1910s, proponents of strict enforcement of the ordinance found themselves in a difficult situation. On the opposing side stood the younger generation – men and women enjoying the new mass culture – as well as the local business elite, lamenting the negative publicity the controversy had created for the region. In 1917, the organization of a bathing suit parade featuring young Hollywood actresses riding in automobiles crystallized the debates. By organizing the event, the Venice Chamber of Commerce hoped to compete with the annual automobile parade in neighboring Santa Monica. Venice had planned to hold such an event the previous year, but after local religious leaders protested the presence of actresses wearing revealing bathing suits in the city’s streets the idea had been abandoned. As Reverend Fenwicke L. Holmes pointed out, a street parade of young women in bathing attire – even seated in cars – would be in contempt of the bathing suit ordinance.43 The city council eventually acceded to the Chamber of Commerce’s wishes and authorized the parade.44 Evidently, the ordinance carried less weight when set against the need to attract tourists to the city.

This decision signaled a major shift in relationships between city council members – primarily businessmen – and local religious authorities. While Reverend Holmes had succeeded in convincing the city council to cancel the parade in 1916, he failed to do so the following year. A few days after the parade, as if to confirm that times had changed, city council members decided to repeal the controversial ordinance and focus policing efforts on male bathers exposing their naked torsos on the beach.45 The city mayor, however, ordered the police to ignore the repeal and continue arresting anyone lounging in their bathing suits 20ft east of the shoreline.46 The dispute between the mayor and the city council continued throughout the August of 1917, each side voicing their point of view in the local press. According to two members of the city council who acted as “bathing suit censors,” the one-piece bathing suit was the only article of clothing appropriate for swimming and, they insisted, did not diminish women’s respectability. Although the city mayor never entirely changed his position, he did suggest police wait till a second violation to make an arrest.47 The debate was eventually resolved by the action – or rather inaction – of the police: not a single arrest was made during August 1917, which the local paper attributed to the unwillingness of police to enforce the law.48 Local police officers were all too familiar with the many practical difficulties preventing strict enforcement of the ordinance and given the council’s concerns regarding arrests, evidently preferred to ignore violations. The ordinance gradually faded into oblivion as over the following years, Venice established its reputation as a resort where young women flaunted their bodies in fashionable bathing suits.

Meanwhile, in 1918 Santa Monica’s mayor published a declaration reminding residents of the exact terms of the bathing suit ordinance in the local paper. Yet there were portents of the law’s inevitable demise. Firstly, in his declaration the mayor also clarified that the city “d[id] not go in for prudish bathing suits” and that there would not be any “foolish restrictions”49 imposed on bathers beyond the bathing suit ban on city streets, revealing fears among city officials that rigid enforcement of the ordinance had scared tourists away and reflecting the city’s resolve to project a modern image. Secondly, to the relief of local authorities, no bather was arrested during the summer of 1918.50 In this context, Alta Johnson’s arrest by Officer Ben Carrillo on July 17, 1919, after a year-long respite, created sensational headlines. The local paper expressed fears the news would reach “uptown papers,” meaning those in the Los Angeles area with a broad readership, and turn Santa Monica into “the laughing stock of liberal minded persons.”51 Given such negative media coverage of the arrest, police felt compelled to drop the case and, at least in practice, abandon the ordinance. On July 23, 1919, Santa Monica’s Police Chief declared that “the innate modesty of the sex render[ed] any drastic enforcement of the bathing suit ordinance unnecessary.” Although he opposed the “unnecessary display of the person or strolls in the business district without proper outer covering,” he believed it was important to allow visitors “as much latitude as consistent with good taste”, and concluded by declaring “this [wa]s not a Puritan age” and the “old blue stocking ideas of some rabid church people [we]re not in vogue nowadays.”52 His statements reflected the widening gap between the attitudes of religious leaders and the business elite. In the end, the city’s need for tourism proved crucial. Moreover, the number of bathers flaunting the ordinance was already too large to stem the tide. In 1919, the one-piece bathing suit “[wa]s omnipresent”53 in the region with many young women wearing it in the city’s streets.54 Faced with daily transgressions of the ordinance and the negative reactions to Alta Johnson’s arrest, the city was forced to relinquish its sartorial control of urban space. It was in Santa Monica that Annette Kellerman famously saved a female bather from drowning the following year. The Olympic swimmer used the event to reiterate her support for the one-piece bathing suit and, implicitly, its use both in and out of the water.55

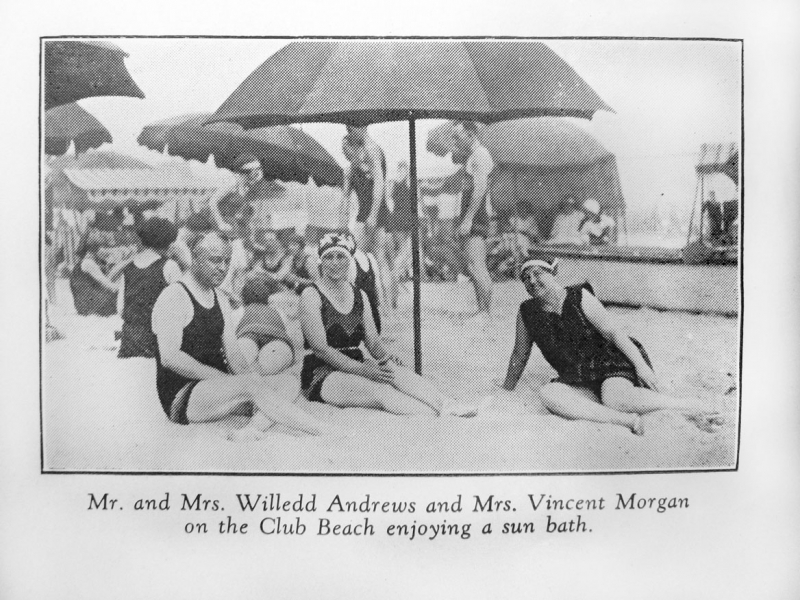

In this photograph published in 1925 in a Los Angeles private beach club’s newsletter, wealthy club members are relaxing in their swimsuits. 1920s bathing suits clung more tightly to the body and revealed the bathers’ shoulders and thighs.

“Casadelmar Topics,” vol. 1, no 6, August 1925, p. 9, box 9, file 16, California Tourism and Promotional Literature Collection, Oviatt Library, California State University Northridge.

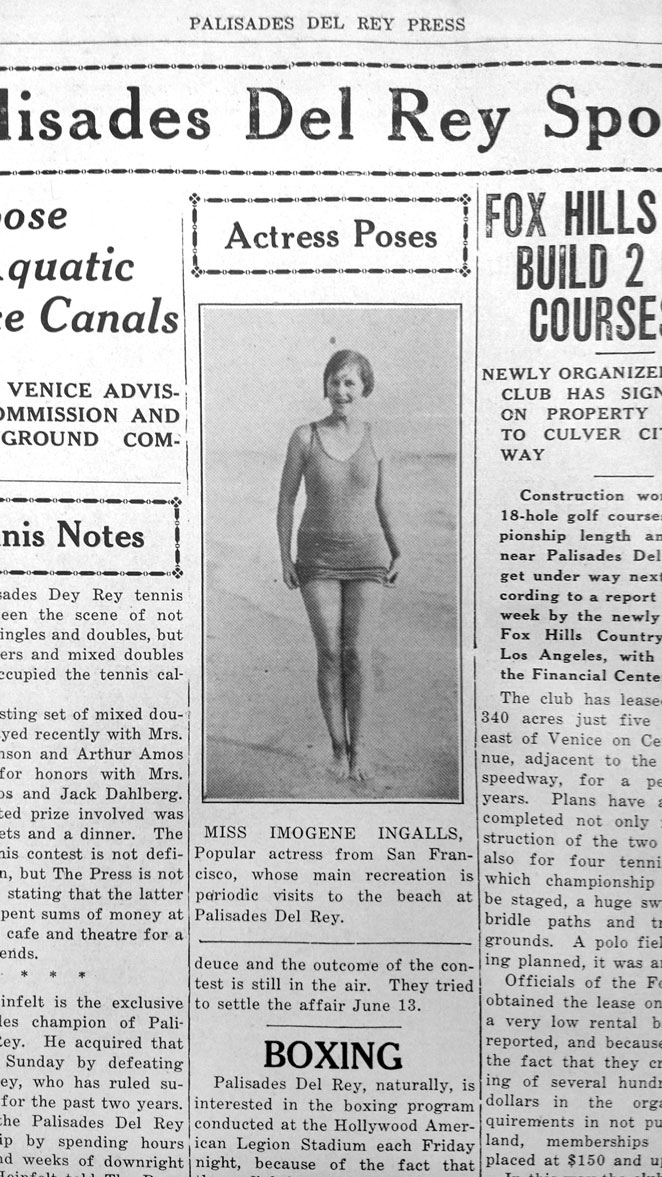

Actress Imogen Ingall on the beach at Playa Del Rey. Palisades.

Del Rey Press, June 15, 1926, p. 7. Fritz Burns Collection, Archives and Special Collections, William H. Hannon Library, Loyola Marymount University.

Over the next few years the ordinance slowly faded into oblivion. The issue did come up again in the 1920s, but this time in seaside resorts farther away from Los Angeles, such as Newport Beach, which attracted increasing numbers of year-round-residents hoping to turn the beach town into a respectable community with high moral standards.56 Aside from a few rare instances, the law was quickly forgotten, and the one-piece bathing suit gained its legitimate place on the beach and nearby areas. Evidence of this transformation was illustrated in the great number of scantily clad actresses photographed on the sands in the early 1920s. One example is a photograph of Imogen Ingalls, a young actress from San Francisco, published on June 15, 1926 in the Palisades Del Rey Press. The young woman is pictured on the beach in a wet bathing suit that clings to her body, highlighting the shape of her hips and breasts. With her bobbed hair, Imogene Ingalls personified the fashionable flapper, a type of young woman who smoked and danced in public in blatant disregard of traditional female behavior.57 In just ten years, attitudes to public displays of the body had been drastically revised. It was now considered acceptable, at least for a young actress, to display her semi-naked body in public. Another example of this revolution occurred in 1921, when the first Miss America pageant was held in Atlantic City, and featured the now notorious bathing suit parade.58

How these conflicts influenced dress codes in the city

The daily transgressions by bathers were part of a larger movement – led by the younger generation, eager to partake in all the pleasures the new mass culture could provide, and a new economic elite – which witnessed the decline of Victorian values in the face of competing goals such as unrestrained fun, extravagance, a quest for youth and beauty, and the public exhibition of the body. These small offences not only changed how people dressed at the seaside, but also what they wore in the city; Los Angeles’ renegade bathers participated in the relaxation of dress codes enforced in urban space far from the beach. In 1941, the Federal Writers Project guidebook on Los Angeles explained that it was not unusual for “beach costumes [to be] seen on urban streets thirty miles from the sea.”59 More broadly, one could make the argument that the casual clothing style so typical of Los Angeles, famously and caustically described by Nathanael West in The Day of the Locust, resulted from the eroding frontier between beach and city. In his famous novel on 1930s Hollywood, West mocked “the great many of the people wore sports clothes which were not really sports clothes […]; the fat lady in the yachting cap [who] was going shopping, not boating […]; and the girl in slacks and sneaks with a bandanna around her head [who] ha[d] just left switchboard, not a tennis court.”60 This athletic and casual style, so characteristic of the city from the 1930s up until today, is indirectly linked to the transgressions of early 20th century bathers. The men and women who, on a daily basis, pushed back the limits of what was considered acceptable in the city, contributed to the relaxation of social norms in public space and, eventually, to the emergence of a unique Southern California sartorial culture.

Conclusion

The influence of seaside fashion on Angelinos’ everyday clothing choices would not have been possible without the relative tolerance of police towards bathers. Although many arrests were made in the summer of 1916, these decreased rapidly over the following years and the ordinance was entirely abandoned in the early 1920s. Strict enforcement of the law, as I have explained, was virtually impossible. Without a dedicated beach police, it proved too difficult to restrict beach activities and fashions to the sand, especially since excessive policing placed the tourism and leisure economy at risk. Ultimately, the ordinance faced constant negotiations between competing interests, including those of bathers, businessmen, religious leaders and local police officers.

While the ordinance was quickly abandoned and eventually forgotten, it provides us with a unique window into the social and cultural evolutions that marked the early 20th century. Firstly, the controversy reveals a major, yet often overlooked, revolution in the history of the seaside: it highlights a transformation from the beach of the 19th century, where one dressed as in the city, to our modern version of the shoreline, where semi-nudity is de rigueur and the body is perpetually on display. Far from being a smooth process, this evolution generated strong tensions, as revealed by the adoption of laws restricting bathing suits to the strict aquatic area of the shoreline. Secondly, the controversy illuminates the emergence of new social norms of public bodily display in a coastal city such as Los Angeles. From the 1920s on, it was acceptable to reveal certain parts of one’s body in the street, on trams and in stores. By making their way into the city, the renegade bathers of Venice and Santa Monica inaugurated a new era in the history of urban public space in Southern California. This evolution was the result of their daily transgressions of the beach/city frontier. By crossing this invisible line, male and female bathers of the early 20th century participated in diluting sartorial expectations and upset the invisible grid organizing urban space. In doing so, they reshaped the city and its laws.

Bibliography

Cindy S. Aron, Working at Play : a History of Vacations in the United States, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1999.

Catherine Cocks, Tropical Whites : The Rise of the Tourist South in the Americas, Philadelphie, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013.

Alain Corbin, Le territoire du vide : l’Occident et le désir du rivage (1750-1840), Paris, Flammarion, 2010.

Christophe Granger, « Batailles de plage. Nudité et pudeur dans l’entre-deux-guerres », Rives méditerranéennes, no 30, 2008, p. 117-133.

John F. Kasson, Amusing the Million : Coney Island at the Turn of the Century, New York, Hill & Wang, 1978.

John K. Walton, The British Seaside : Holidays and Resorts in the Twentieth Century, Manchester, Manchester University Press, 2000.

Jeff Wiltse, Contested Waters : A Social History of Swimming Pools in America, Chapel Hill, The University of North Carolina Press, 2007.

Film

The Beach Club, Mack Sennett Comedies (1928) (on Youtube : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5SQhq6LVNiI)

Book

Nathanael West, The Day of the Locust, New York, Random house, 1939 [French translation : L’incendie de Los Angeles, Paris, Seuil, 1961].

Websites

Photographic collection of the Santa Monica library: http://digital.smpl.org/