Joint interview with Jane Aubaile, Dominique Veillon, historian and director of Research at the CNRS, and Beatrice Behlen, Senior Curator, Fashion and Decorative arts, Museum of London.

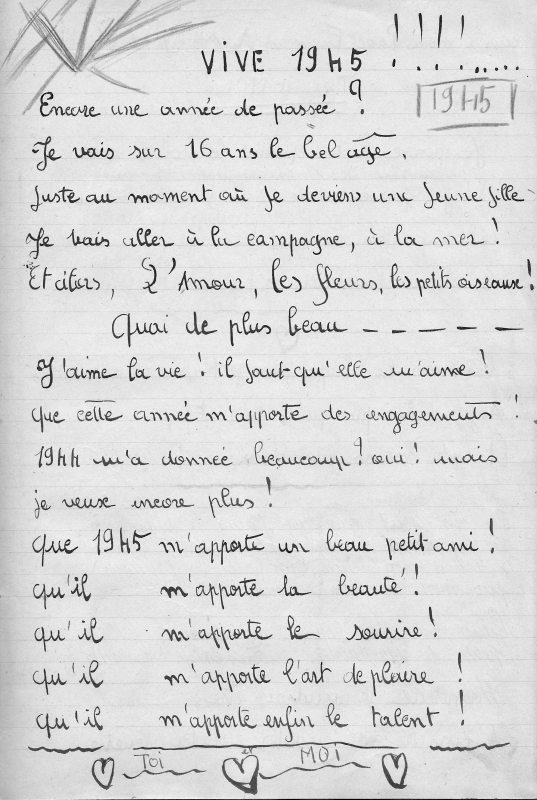

Jane Aubail kept personal diaries during the Second World War and in the early post-war years, between 1944 and 19511. An adolescent during the war, Jane’s testimony offers a singularly youthful perspective on occupied France. Her journals are invaluable for historians, and especially so for fashion historians searching for information on the reception of trends, everyday practices, and patterns of consumption at the time.

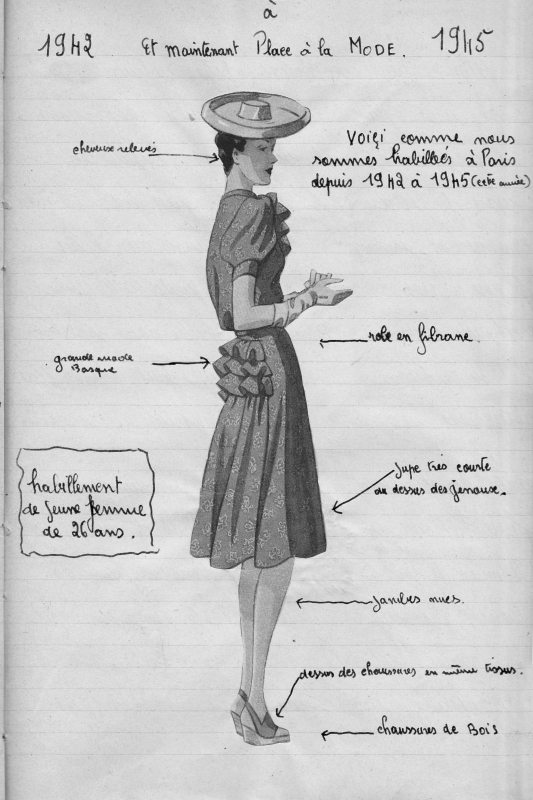

During WWII, fashion became an important economic and ideological issue for Germany, which sought to make Berlin the capital of haute couture, to the detriment of Paris. As historian Dominique Veillon demonstrates in her book La Mode sous L’Occupation, restrictions on textiles and primary materials, strict rules imposed by Nazi Germany on the display and exportation of items, as well as the personal difficulties faced by the couturiers and the highly controlled female press all weighed heavily on the industry. For a population relying on rations tickets for their clothing, renewing one’s wardrobe became practically impossible without significant means. One had to make the old new again. Idioms such as Système D and débrouillardise were popularized to describe the scrappy resourcefulness that became necessary. A collection of near-mythical images testify to the methods: wide brimmed hats made of newspaper (only for the wealthy minority; most wore wraps, berets, and fedoras), shoes with wooden soles, and dyed legs (with a line penciled in behind the calf) standing in for unobtainable stockings. Yet just as indelible are the color photographs of a joyous, light-hearted Parisian quotidien under Occupation, taken by the photographer André Zucca, in service of the Germans.

Confronted with the research of Dominique Veillon, the lived experience of Jane Aubail, and the documentation in her journals, we’re given an opening into the myths and realities of these images. The dialogue between sources allows us to analyse the state of fashion during the war, while also examining the contradictions and congruences between various depictions of the past; with oral history and memory – occasionally errant – meeting up against primary documents, archival research, and sometimes false accounts in the press.

Recollections of wartime life and its aftermath in private diaries

Sophie Kurkdjian When do these diaries start?

Jane Aubaile August 1944, when Paris and its outskirts were liberated. But I started writing earlier, when I saw Belgians fleeing the Nazis at the rally in Luna Park. I was very young then. Seeing them all assembled in mass made a lasting impression on me. That was just before the war in France, in 1940. I started writing frequently, but those journals are lost. And I can’t remember everything from then, I’ve forgotten quite a few dates.

Dominique Veillon That’s the difference between a witness and a historian: I was struck when I was talking to you about this period, because it’s very different from what I wrote about those years… perfectly normal since your diary doesn’t start until 1944. You don’t bring up the status of jews, or rations tickets…

SK Do you remember the moment when you said “I want – or need, even – to keep a diary”?

Jane I felt the need to write when I was very young. Growing up in a blended family, with step siblings, I felt the need to express myself. And, either way, it wasn’t customary to listen to children at the time. I started writing right at the start of the war – we had rented a house near Saint-Malo, at Rothéneuf. That’s where I started writing, when I was still a little girl.

DV Were you there for vacation or in exodus?

Jane My father was a vendor for Desmarais-Freres, the cooking oil company. With what he received for hotel and restaurant expenses, we had enough to rent a house. That was right before the war, 1938-1939, I think, because I remember the day he came back with his conscription order in his brand new Renault, provided by Desmarais-Freres. Everything’s there, more memories keeps coming back as you ask the questions.

SK You started writing then, and all through the war?

Jane Throughout the war, yes, but I didn’t keep anything. the first diaries that I kept are from August 1944.

SK How did you obtain the notebooks, given war-time scarcity? [27 leather bound booklets, tied together with ribbons]

Jane I had a half sister who was 17 years older than me, Andrée. She was brilliant. She was executive secretary for the paper companies of Domainons, in Savoie. And those companies tasked her with opening stationery shops in Paris, right during the occupation. She had German officers as clients. That was on Boulevard de l’Hopital by the Pitié Salpêtrière hospital. One officer, who was a regular client, ordered 30 notebooks for his office, but she only received them in 1944, at the end of the Occupation. Since I scribbled all the time in little exercise books, she told me she’d bring me the notebooks.

DV Paper was reserved for Germans, who forbid its sale in order to prevent the distribution of anti-Nazi tracts.

Jane True, my sister had authorisation to sell paper, for each order, from the Kommandantur. In 1944, she started bringing back the notebooks, little by little. In the end, I got 27, even though I’ve only recovered 25. I started writing… and I stopped writing when my life turned into that of a woman, when I showed up in magazine Miroir du Monde, thanks to Henry Dupuy-Mazuel, who wrote Miracle des Loups and directed Le Monde illustré before he was at Match. I needed to start making my way in life.

Sophie Kurkdjian Beatrice Behlen and Did you reread your journals afterwards? After the war?

Jane No. I wanted to give them to my mother with a wax seal, but even without, she never opened them. Afterwards, I never showed them to my family. We opened them just recently, with my son and my granddaughter Sarah. I haven’t reread them since, I don’t look towards the past.

SK Did you have a regular schedule for writing?

Jane No. We were a family of six in a three room apartment. I didn’t want to write in public, even if no one else paid any mind. Those were my deepest feelings, and I didn’t want to expose that side of myself to my family. When things were going badly, I hid out on the sixth floor, in the tiny maid’s room where Elise stayed, the woman who raised me, and I brought my notebooks. It seems picturesque, now… it wasn’t at all.

SK What role did these personal diaries play for you? How did you use them? As confidants or friends?

Jane No, not as confidants. It needed to get out, however it could.

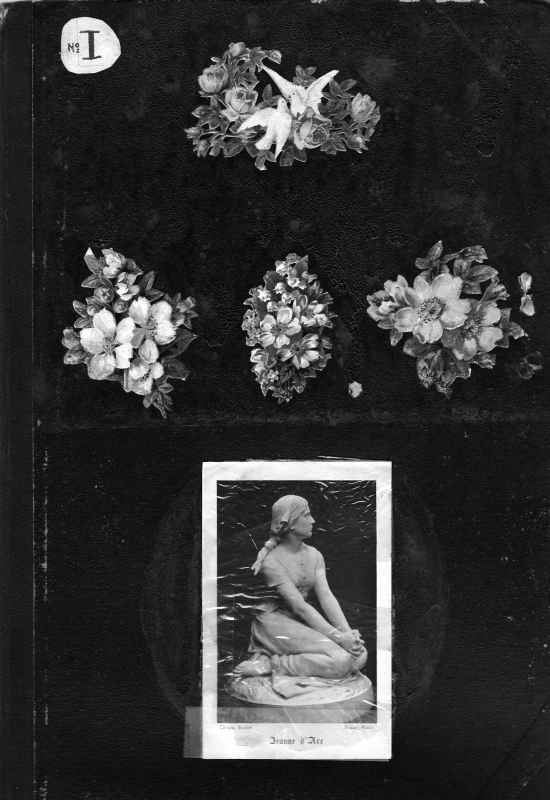

SK There are a number of cuttings and collages in there. Where did you find the images?

Jane At the time, everyone who lived in apartments opening onto the courtyards talked to each other (but not with those in the apartments in the front). [Jane lived on Avenue de Neuilly, now Avenue de Charles de Gaulle, in Neuilly]. Everyone knew each other. The maids were on the 6th floor. And I was the smallest in the building, so things were set aside for me. When the families retired for the evening, the maids would bring me magazines and fashion journals. There was Modes et travaux, travaux pratiques… and some other journals that the Germans allowed, that disappeared afterwards. And then postcards, some very old, that you could buy in the markets. I cut them up, glued them… but nothing was easy. For example, getting the glue was complicated. My half brother, who was nine years older and studied at the Beaux-Arts, made me glue. Everything was missing.

DV In 1944, when these notebooks first appear, everything was still rationed. For a few days after the liberation, some things, notably bread, were allowed to be sold without rations, but rations tickets returned very soon. The last coupons were eliminated in 1949.

Jane I remember rations tickets with the grams allowed for butter or bread… but everything went through the black market. Those without money had nothing. My father, being in the oil business, did fairly well with exchanges on the market, so we ate a bit better.

Maude Bass-Krueger Did those images you glued in your notebooks inspire you?

Jane They related to me, I wanted to be those women.

MBK And where did you meet them? In the streets or in magazines?

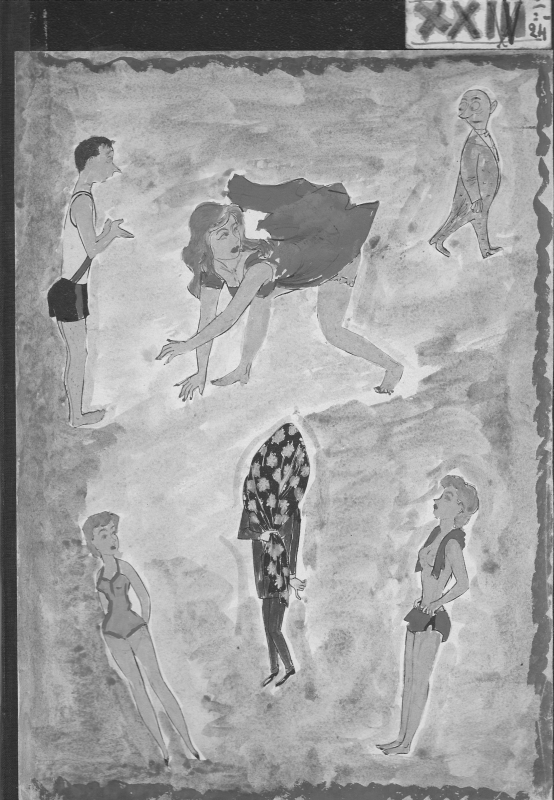

Jane We already had a number of couturiers at the time and there were the few fashion magazines, but mostly windows with pictures of models. The most beautiful windows were at the Palais-Royale. It was an event, you went to the “arcade” to admire the windows of different couturiers. I studied closely, and then, returning home, I would draw sketches. I wanted to be those women. I was fascinated by fashion. Fortunately for me, my mother was adept with costuming. In 1912, she went abroad with the tour for the Comédie-Française. She always loved fabric and dress, but from the perspective of the theatre. She knew how to cheat. With the little fabric there was during the war, she managed to create her pieces. She made her own costumes with a little Singer [sewing machine]. She also brought back an English sewing machine from one of her tours in London.

DV And how did she manage to procure fabric during the war?

Jane At Montmartre, vendors sold under the table. Fabric was much more expensive, often double what it was before the war.

DV Without rations tickets?

Jane Yes, it was all black market. They would discretely hand the cloth to us, inside newspapers. Often, you couldn’t choose the color. I remember getting a dress in teal colored corded fabric; we only discovered the color opening up the newspapers at home.

MBK And where did she get the patterns?

Jane That was easy. You couldn’t buy clothes, so patterns were everywhere. You could get them in magazines, and also at Montmartre, there was a specialized store for it. I still have some relics from Galeries Lafayette, undoubtedly from after the war, the paper almost in shreds.

DV Patterns printed on thin, poor-quality paper were common in women’s magazines, and you can still find some today in journals from the 40s.

SK Were you attracted to specific styles?

Jane I had a set idea. At the time, I had long, beautiful hair and I was very thin. Thin hair and figure; that was the rage then. I remember the guepière waist-cinchers of the girls who were older than me.

DV The trend was launched by Marcel Rochas in 1941, and spread widely after the war.

Jane Guepières tightened around you in marvelous way. I clearly remember walking along the Porte Maillot, where the Palais de Congrès is now, everyone was looking at me in my guepière… I was happy.

DV And all your friends had the same desires?

Jane Yes, I think, but I talked to my magazines more than my friends.

Jane Aubaile's private diaries form 27 volumes and span from the Occupation to a few years after the Liberation.

Jane Aubaile's private diaries form 27 volumes and span from the Occupation to a few years after the Liberation. She writes about “her” war.

Jane Aubaile's private diaries form 27 volumes and span from the Occupation to a few years after the Liberation.

Jane Aubaile's private diaries form 27 volumes and span from the Occupation to a few years after the Liberation.

Hats made of newspaper, wooden soled shoes, dye masquerading as stockings: myths or realities from WWII?

SK Shoes with wooden soles, hats made of paper… do you have any memory of those practices?

DV Paper hats were, above all, made by the big couturiers for a minority of consumers.

Jane Not just! No one went without a hat. I also remember various turbans and wraps. Fishnets with artificial flowers holding the hair were also very fashionable. You could even buy nets made out of hair at the hairdresser, if yours was lacking. My sister wore them, I was too young. Sequins and ribbons were added in the evenings. Only maids went out hatless. But I was too young for all that. My mother made me up bérets, and afterwards I would wear bucket hats like Deanna Durbin. I remember Bettina…

DV But that was just after the war. During the war, the fashion of hairnets made out of hair was very brief. The were soon requisitioned to make slippers.

Jane Yes, it’s true, I remember that they were requisitioned.

MBK Do you have other memories of fashion then?

Jane Yes, the petticoats that were worn under samba style skirts, like the dance. The underskirts were often made with old sheets. I remember that washing was always very complicated, hair washing included. My mother washed my hair with lemons, but those were hard to find. I also remember bandoulière shoulder bags; you know where those came from? From gas masks. We went to the mayor to pick up the gas masks that we were supposed to have on us at all times. One designer, I don’t know which, launched the gas mask toting shoulder bag.

DV This fashion started early in the war due to lack of conventional transportation and the increase in bicycle use. Shoulder straps allowed women to carry their things with them while keeping their hands free.

Beatrice Behlen Did your sister use makeup during the war?

Jane Yes, she was working, and she liked to get dressed up. She would go to Anna Love on the Champs Elysées, a prêt-a-porter boutique. She put on makeup frequently.

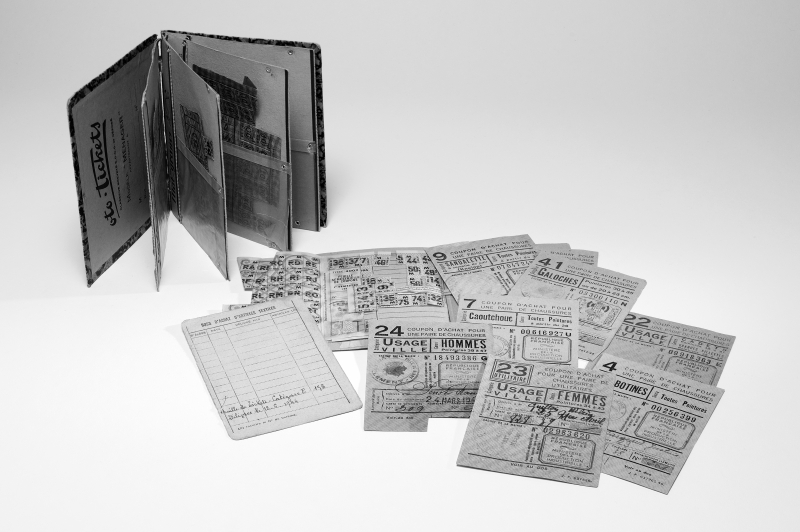

Ration books and tickets for shoes; card for textile purchases delivered by the Ministry of Industrial Production.

© Collection du Musée des Métiers de la Chaussure, Romans.

Handbag of Marie-Émilie Brachet-Veyrier. The contents reveal wartime habits during times of shortage, when even the smallest threads or matches were kept for times of need.

CHDR © Pierre Verrier.

Men’s derby shoe, woven plant fibers, handmade using the technique used to make hats. Worn in Coulonges-sur-l’Autize, Deux-Sèvres.

© Fonds Chauvin, collection du Musée des Métiers de la Chaussure.

Men’s derby shoes with wooden soles; slats cut into the wood intended to help with the flexibility of the sole.

© Collection du Musée des Métiers de la Chaussure.

Storage box for a gas mask and large handbag made from leather scraps (the manufacturing of leather bags was prohibited from 1941 on).

Women’s handbags became larger during the Occupation, as they were used to carry as many things as possible in case of a sudden departure.

© Prêt René Lefort.

Rep ribbon and stacked wooden sole, varnished and cut out.

Nearly everything was rationed except for ribbons, which could be purchased without a ration ticket as long as they were less than 20 cm wide. They came in a variety of colors.

Collection of the Musée international de la chaussure, Romans © Pierre Verrier.

BB There are a number of sketches in your notebooks. Would your mother create pieces from your designs?

Jane In 1942 and 1943, we made a lot of floral dresses. My mother cut out flowers and added them onto a set of organdy puff sleeves – I don’t know where she found them… It was an incredible dress, my sister wore it as well. I would give her an idea of what I wanted, sometimes with pictures, and she would piece it together. I remember, once, I wanted a tartan dress-suit.

DV That was very much in fashion during the war.

Jane At Montmartre, the salesperson found us an orange and green pattern with a black background. We discovered it once we got home, this time really pleased. My mother made me a straight wrap skirt with fringed edges, that closed on the side. That was maybe a little after the war… I can’t remember because I wore it for a while; in that era, we wore clothes for a long time. I really loved that outfit, I wore it on my first date, and leaving the movies, the boy said that he wouldn’t forget me, with the carpet I was wearing! That stuck with me… I never saw him again. On the other hand, I kept the fringed scarf I was wearing then for 40 years, it was quite sturdy.

DV In La mode sous l’Occupation, I tell the story of a young girl who wore a tartan skirt throughout the entire war, and at the end, it was so worn that she made a bag out of it.

Jane Yes, it was really a different time. Back then, we all knew how to knit. I learned early, and could make sweaters. During the war, we were all looking for wool. Many women would knit gloves for the prisoners…

DV Those were parcels for prisoners in Germany. Usually, the packages would arrive at their destination. Fashion journals would give away patterns for those clothes.

JaneWomen were knitting everywhere, even in the subways. It was tough to find needles – we would usually lend them to each other – and the wool was often poor quality, with the threads always breaking.

DV Would you unravel your pieces as well?

Jane Yes, knitting was a huge part of our lives. I would unravel in order to knit something else, and I would also wash skeins of wool. We don’t know how to do that today. That’s also why I kept my notebooks.

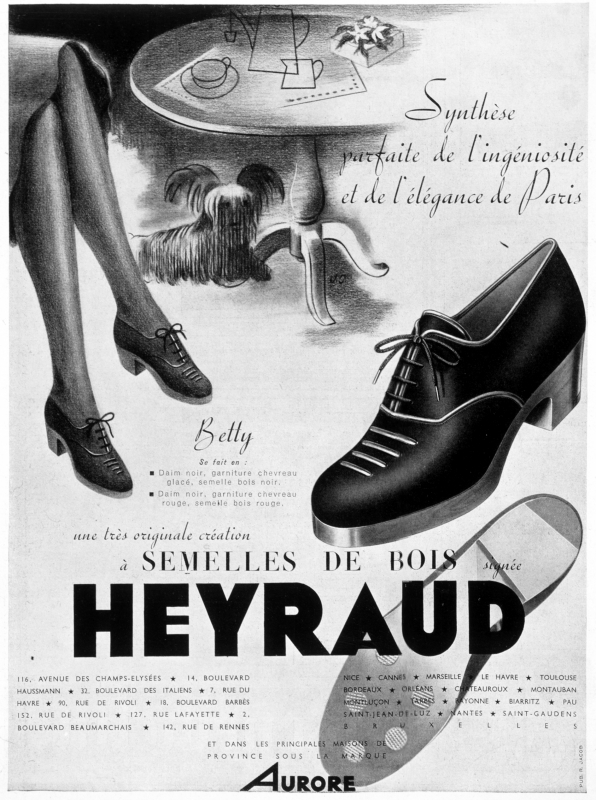

SK Were shoes with wooden soles common in Paris?

Jane Yes, there wasn’t anything else… but I never wore them, since I was too young. My sister did. They were called semelles compensées [platform soles] or semelles articulées. They were very heavy – and loud, before you put on cork. As for me, I wore sandals.

DV With bobby socks, like all the young girls?

Jane Yes, of course, it was unthinkable to have bare feet.

SK And painted on stockings, were those real?

Jane Yes, we had no stockings. We had dye; you had to find the right color and find someone to trace a line on the back of your leg. My brother, who was at the Beaux-Arts, did it for my sister; I remember, once, he drew a horizontal line on one of her calves, and we caught it before she left for work. Afterwards, we had stockings made of rayon.

DV Then, later, with the arrival of the Americans, came nylon stockings.

Jane For the rayon stockings, which were always getting runs in them, we had the ramailleuses [stocking menders]. They were women who often set up shop in the windows of the dry cleaners and dye shops, close to the light. You paid by the length of the thread. Later – after the war, but I can’t remember when – someone had the bright idea to set up that service in train stations and at subway exits.

DV You could still find them in the 70s, I remember.

SK Did one dye one’s clothes then?

Jane Yes, often. Since we wore them all the time, we wanted to give them back some color and freshness.

DV Advertisements for tints and dyes are everywhere in papers from the time. Mourning attire was often dyed as well.

Jane Mourning was given an incredible significance. I remember one woman in our apartment, who lost someone close to her, who wore a crêpe veil that went down to her waist. Those women in mourning frightened me because they reminded me of bats. Afterwards, they would wear the half-mourning dress in mauve for two years. And the men wore brassard armbands for two years. You were tied to those rules. I remember a shop that scared me in Ternes, that specialised in dyes and mourning attire.

DV These customs were also very important from 1914-1918, and were eventually abandoned in the ‘60s. 1968 brought an end to all that.

BB Did one wear black outside of mourning?

Jane During the war, no, black was reserved for mourning. We wore very little black, especially young girls.

DV Was the word “restrictions” familiar to you at the time?

Jane Yes, for example, you couldn’t walk into just any store to buy fabric.

DV Do you remember the rations ticket for clothing?

Jane No, I remember the ticket for butter, 20 grams I think, and those for other foods.

DV It existed starting January 1941, but perhaps it was your mother who kept it, as was the case for most families. And your father was active on the black market, as you say.

SK“System D,” “debrouillardise” [resourcefulness], do these two terms characterize the practices at the time ?

Jane Yes, along with the black market. Everything was done with money. Without it, you died of hunger.

DV It was a sort of “grey market,” or parallel market meant to satisfy familial needs – especially in Paris, where the ration wasn’t sufficient to live on. Family packages were also allowed.

Jane For Christmas, we would get a package from the family in Creuse. We would go to the station to retrieve it, in order to avoid stealing. There was also a lot of black market dealing in restaurants. First of all, you ate when you paid, which was abnormal… and in certain restaurants, the staff would sell the leftovers.

SK Lucien Lelong, Maggy Rouf… do those names mean anything to you? Did you know about the Nazi project to change the fashion capital of the world from Paris to Berlin?

Jane Yes, my brother kept me well informed. He was surrounded by intellectuals at the Beaux-Arts, those who wouldn’t allow themselves to be fooled by propaganda. He paid attention to these things. We would talk about it; it disgusted us. My brother, by the way, was decorated upon liberation, at the Marie de Paris.

DV I think it must have been after the war, because the project was kept secret. It was only after the war that we learned what was menacing haute couture. As for Lelong, he was tried for collaboration, but – defended by his peers – he was exonerated for the majority of it, under the pretext that he was protecting employment under occupation.

SK Do you remember German fashion magazines at the newsstands?

Jane Not in the kiosques. But I had some that I cut images out of. I lived in a bourgeois building and the maids would bring me fashion journals, including some German ones.

SK Did any designers inspire you?

Jane Jacques Fath. All the women around me were in love with him. I thought he was extraordinary… he was married, with kids.

DV And his wife, Genevieve Fath, was his favorite model. Jacques was a collaborator, very pro-German. The archives are unequivocal on that front. He opened his own fashion house in 1939, even if he would claim afterwards that he opened it after the war. The Germans loved him because he was young and handsome… even if he wasn’t quite at the level of Maggie Rouf and Marcel Rochas, who were even more zealous collaborators. They both communicated with the Germans and didn’t hesitate to show their collections in private for them. Marcel Rochas was even ready to open a house in Berlin.

Jane There was also Grès at the time. And Chanel…

DV Yes, but there was only talk of Chanel’s collaboration after 1954. Before, it wasn’t discussed. Arrested at the Liberation, she was freed thanks to an intervention from a high ranking Englishman. In exile, her fashion house was closed down, and would only reopen in 1954.

Jane Yes, we did talk about it after that… but that doesn’t take away from her talent. And Schiapparelli?

SK She was in the United States. For Chanel, did you know that she shared her life with a German?

Jane Yes, we knew. Through the press…

DV Surely not through the press, since it was censored. Maybe after the war, when it was much talked about...

Jane Perhaps I picked it up from the can-can dancers’ gossiping.

BB You said that Madame Grès made costumes that you wore?

Jane Yes, for the theatre. I never had any desire to be onstage, but my mother dreamed that I follow in her footsteps. My brother, who needed money – he was 17 – was hired by the Edward VII theatre to draw and paint the props. He brought in my photo and I was chosen for the role of Peas-Blossom in A Midsummer Night’s Dream… in April 1945. Madame Grès made all the costumes.

DV It’s not surprising that she was chosen, she was a specialist with pleated fabric. The Germans, troubled by her patriotism – she created dresses in blue, white, and red – closed her store in January, 1944. She reopened it in March, but could no longer use pleated fabric, due to a lack of material. [Jane Aubaile leafs through her notebooks]

Jane This was my own collaboration… in 1942. I was 11. I’m at the Grand Palais, it was filled with Germans. I was taking part in a children’s choral ensemble mandated by my school, École de Madame Patornie Casadesus. I remember that everything was controlled. It was very strict, we couldn’t use the restrooms alone, we were always accompanied by a German woman in uniform… I’ll stop there, but I still have a lot of stories to tell on my history with coquetterie and fashion!

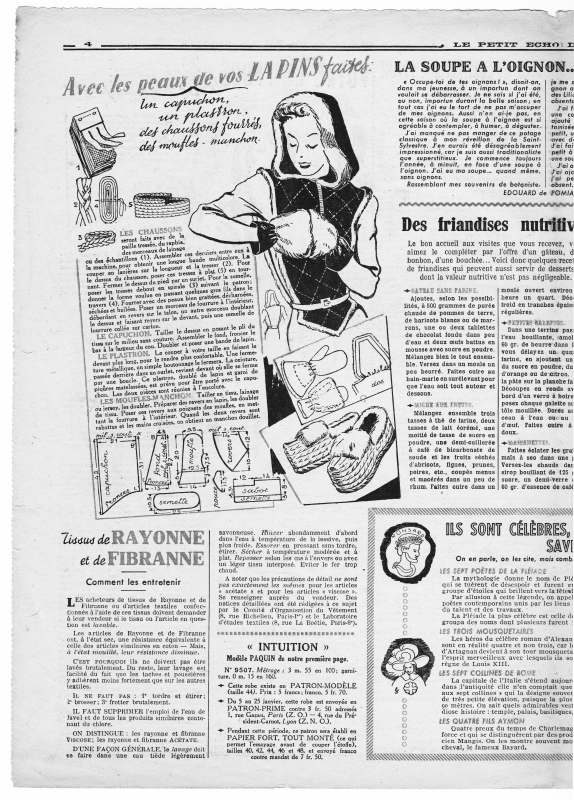

“Avec des peaux de lapins faîtes:…” article published in Le Petit Écho de la Mode, January 17, 1943.

Collection Claude Tiano, Musée des 3M.

Restrictions, la gaine de qualité, Scandale, advertisement from 1941.

© Collection Kharbine-Tapabor.

Advertisement from 1941 for wooden soles from Heyraud: “Perfect mix of ingenuity and Parisian elegance.”

© Collection Kharbine-Tapabor.