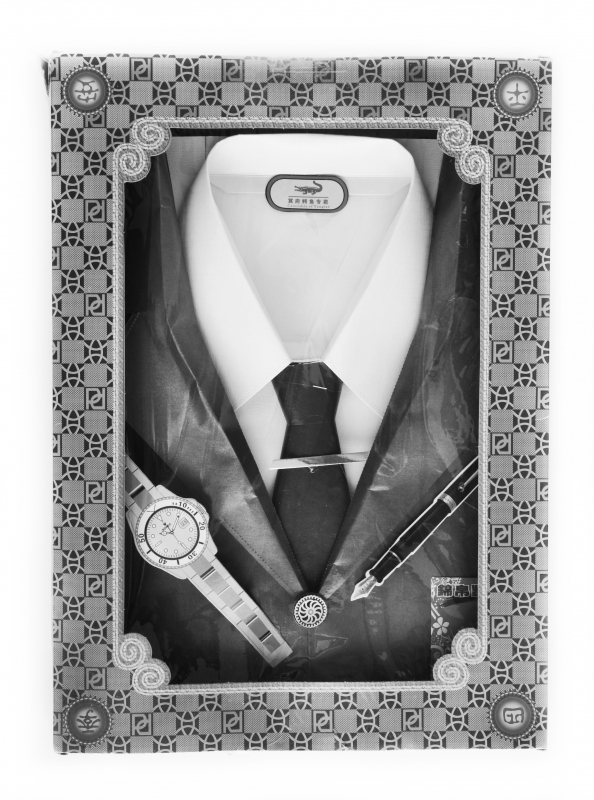

Comprehensive assortment “Lacoste-Rolex-Aurora” in paper, Chinatown, New York, 2013.

© collection Manuel Charpy. Photograph, Manuel Charpy.

In April 2016, the Italian luxury brand Gucci sent a warning letter to shops in Hong Kong that sell paper replicas of their products, asking them to stop selling the items bearing Gucci logos. Found in shop windows on some streets in the city, these luxury paper items are frequently clothes, handbags, and other fashionable articles but also upscale, high-end ipads, miniature cars, or villas. They are all bought to be burned as offerings to deceased parents, to provide for their needs in the spirit world. The demand for these products is especially high during the festival Chingming (tomb-sweeping day) which took place during that period of the year. These warning letters avoided any and all threats of legal action but indicated their concern about the misuse of their brand image – it was an infringement of their trademark – and the “counterfeiting” that commerce in the hereafter could encourage2. Despite the representative of the brand repeatedly expressing respect for these funeral customs, the news went viral and a wave of protests spread through the media and the social networks; the “Gucci Affair” appeared on the horizon. The Italian luxury brand has been made to look petty, to say the least. Disrespect towards filial piety and jokes on the Net concerning Gucci’s hidden intentions to intervene in the invisible market or to open branches in the hereafter to earn “spirit money” and “money from the banks of the deceased” formed the bulk of this slightly surrealistic scandal.3

Paper Catafalques in Chanel Suits

Urbanization and imports of foreign products have played a considerable role in the transformation of Chinese lifestyles in large cities since 1997, when the Chinese market again looked West for whatever was considered trendy and innovative.

The “nouveaux riches” were experimenting with Western lifestyles as leading luxury brands set up shop in all the large cities. Louis Vuitton opened its first shop in Shanghai in 1995; 20 years later the brand has 47 stores in China. Hermes has opened 21 boutiques and Chanel 13. The saga of luxury in China has fused with that of Western designer labels. Thus, each year, not only in China but in Hong Kong, Taiwan, Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, Thailand, and Indonesia, millions of “luxury” jackets, pants, suits, shirts, and shoes, and even passports and planes4, go up in smoke. As a goodwill gesture, occasionally salespersons offered flight attendants – in paper!

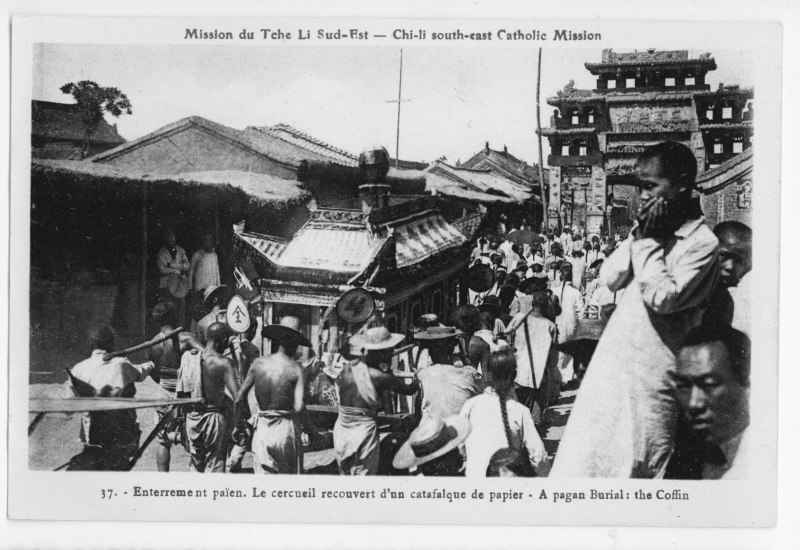

“A pagan burial. The coffin covered by a paper catafalque”, photograph published by the ChiLi south-east Catholic mission, administered by the Jesuits, 1930s.

© private collection.

This traditional ritual has nothing to do with public “autos da fe” aimed at proving that the countries cited are actively fighting counterfeit markets. Burning paper objects as an offering to the deceased, ancestors, or gods, is a time-honored practice that has existed in China since the Imperial Age. This tradition has been transmitted from generation to generation; everyone is involved, nobility to commoner. Texts confirm that paper objects have been burned on important occasions: the burial of a mandarin, the birthday of a deceased, holidays consecrated to gods or spirits and the New Year.

At the end of the nineteenth century, missionaries, filled with their prejudices and misunderstandings, observed what they considered farcical: the pomp, the processions of coffins in the streets, the ostentatious luxury of the assembled paper canopies for the mandarin funerals.5 In 1900, Leroy, compiling letters from Jesuit missionaries gave an exemplary description:

“Father Simon has described the pomp of a mandarin family’s pagan funeral in Nanking. There is nothing more rich, but at the same time nothing more ludicrous. Around eight-thirty in the morning the procession begins; it opens with a cardboard beadle being pulled by a beggar with the help of a rope, followed by six horsemen on gaunt horses with more or less fifteen sordid lads flocking around them. These wretched ones are in all the processions. Their presence is a testimony to the alms spread among them through the generosity of the family either in mourning or celebrating. After these bare-footed urchins come four giants that look to have got lost in China from the kermesses6, those Flemish village fairs. Their clothes are magnificent, including ceremonial hats and boots. Their mission is to defend the dead against evil spirits from the grave and to escort the ancestral tablets. These tablets, superbly decorated and fifty or sixty in number, move forward, balancing in the air the family titles and recalling their important undertakings. The group praying follows the porters, sixty monks reciting and supposed to be saying the Buddhist rosary. If the habit makes the monk, their tonsured scalps do remind us of our Trappists, with their long homespun clothing and their uncovered heads. They precede other moving machines, the names of which we do not know. Can we call them giants, towers, ships? It is difficult to describe these strange contraptions. Among them, a barge ridden by children playing and sparring, with groups of musicians in between the floats and cavalcade. To merge natural elements to these funerals, they pull, always by the same rolling machine, forty of the biggest animals in creation. They remind us of our wooden horses coming from a fairground cart. But here, along with our aristocratic horses, are found steer, bears, lions. The march thus enlivened for a brief moment, resumes its grave demeanor. Very important persons on horseback, men of letters, mandarins of the family, surround a richly decorated palanquin. There is a picture of the deceased, as if sitting on cushions. Other monks in dazzling costumes are followed by priests of reason bringing up the rear of this austere group. The show recommences with four life-sized marionettes. Most of them have only one foot attached to a pivot on a board, easily shaken. At the least shock, all these marionettes collide, tumble over and exchange greetings with silly gestures. These appear to be the servants of the deceased. They have every reason to rejoice because their duties will be neither cumbersome nor difficult.”7

For all practical purposes, of course it is not possible to relate here all the destinies reserved for traditional funeral practices of paper offerings associated with temple or cemeteries. The missionaries were rarely accommodating regarding the practices they defined as “pagan”. The Republic of China’s Central Bureau of Cults itself denounced from 1912 these practices as “superstitions”, reiterating as such, a Western posture.8 The Chinese communist regime interdiction of these “superstitions” or more recently as a source of environmental pollution because of smoke and ashes, has caused a clear breach and has seriously disrupted family customs. Vincent Gossaert and Fang Ling have commented on the anti-religious and anti-superstition laws of the Chinese communist regime at the same time prohibiting the burning of paper offerings, but at the same time imposing cremation since the 1950s.9 Nonetheless, since the years 1980-1990, the liberalizing of cults and the explosion of the market for funeral items has favored the resurrection and growth of paper offerings, including the consumer and fashion market, as illustrated by the Gucci Affair.

Most of the studies dedicated to this market of paper offerings – Janet Scott’s comes to mind – were conducted from Hong Kong and Taiwan where this ritual is neither prohibited nor penalized. But it is not the same thing in the People’s Republic of China. For example, in my hometown of Qingdao signs are posted at the entrances to cemeteries forbidding paper burning to honor the dead, with reasons that have changed with time (hygiene, pollution, etc.). But people indeed have continued to burn these offerings, taking advantage of a certain ambiguity in the law. The prohibitions have been revised and suspended from time to time, which has contributed to uncertainties until even now.10

The practice of assembling and dressing up paper in traditional funerals of Chinese communities has long been the object of studies by historians and anthropologists, notably Dard Hunter, an American author who published as early as 1937 Chinese Ceremonial Paper: A Monograph Relating to the Fabrication of Paper and Tin Foil.11 More recently Ellen Johnston Laing and Helen Hui-Ling published an aesthetic book entitled Up in Flames: the Ephemeral Art of Pasted Paper Sculpture in Taiwan,12 and C. Fred Blake has been monitoring the issue of “paper money” very closely.13 But the most documented study with regard to the collection of objects – including “objects of collection” – and practices observed, is Janet Lee Scott’s, For Gods, Ghosts and Ancestors. The Chinese Tradition of Paper Offerings. This work shows as much interest in the producers, retailers and loyal customers as in the motivations of parents and offspring.14

Paper offerings shop several days before the Têt festival, at the Buoi market, Hanoi, January 2012

© Salomé Gilles.

Têt festival, private household burning clothing for the home’s patron saint, Hanoi, January 22, 2012.

© Salomé Gilles.

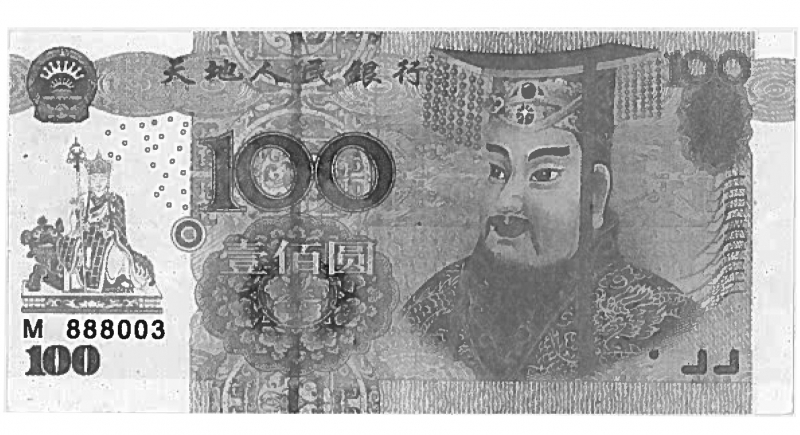

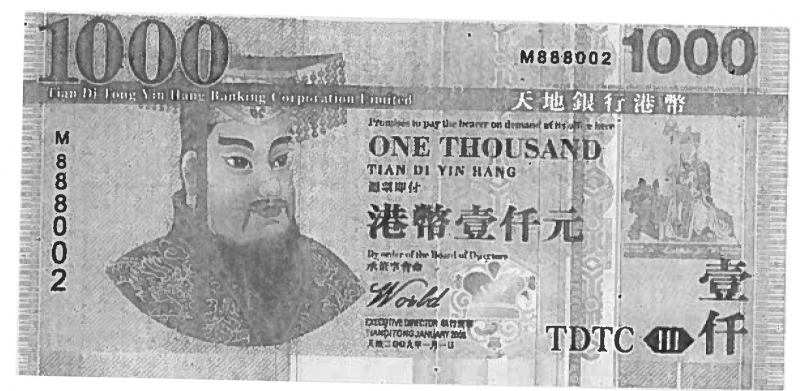

The “Burning” Paper Economy

Shops selling paper objects have always been very profitable in cities and towns nearly all over China. The fate of today’s items is linked to how they are crafted, their sources of inspiration and the types of shops selling them. Their destiny depends on the relationship the customers have built with the shopkeepers. Choice of objects, where and when the objects are used are all important and also the changes in meanings and feelings transferred to these special objects. The variety of offerings reflects the consumer market and the aspirations, or dreams, of the consumers, living or dead. Thus, more and more prestigious technological brands are to be found as well as luxury products embodying the image of “the good life”. Banknotes representing large sums of money hold an important place in this “market” of offerings.

According to Janet Scott’s typology, volume and capacity showcase the shopkeepers’ differences: wholesaler, retailer, licensed stall, seasonal mobile stall. Apart from Taiwanese wholesalers with suppliers in mainland China or in South-East Asia, all other supply chains, from manufacture to sale, are family-owned. Retails shops might be a stall of 3 x 2 meters, perhaps a private 2-story building, perhaps the ground floor of a department store measuring 200 square meters, giving the troubling impression of finding oneself confronted with a big supermarket, albeit in paper! In addition to these permanent stores, hawkers with or without a commercial license, expose their wares on handcarts. They are found most often near large urban cemeteries, particularly during holidays.

Loyal customers can be divided into two groups: those associated with the temples, some “temple-customers” serve as intermediaries, buying paper in bulk to resell to workshops or to private individuals, and an ever larger number of private individuals, as burning paper offerings near temples has become such a widespread practice.

Redevelopment and downtown rental fees have caused the relocation of department stores towards the cities’ outskirts while smaller mom and pop stores have remained in center city. Workshop production and sales are divided among family members, mostly the adults. But occasionally during holiday season, the children come to help their parents, as the number of customers can double or even triple. An old shop that has managed to endure these changes and stay downtown owes its longevity to the trust it has built up among its customers. Of interest, the salesperson himself is also attached to the value of these paper objects, as the respect gained from the deceased is to his benefit as well.

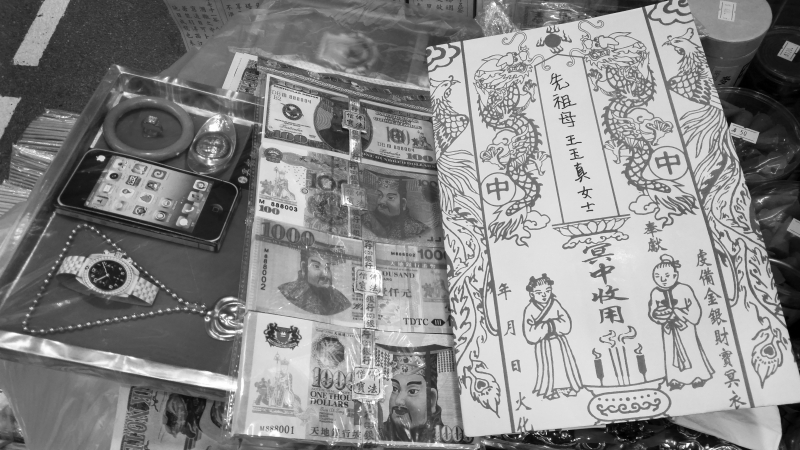

Box for set: Cartier watch, necklace, iphone, bracelet and gold lingot for a woman; Banknotes for Hells; envelope decorated with antique figures in which are placed offerings to burn. Hong Kong, 2016.

© collection and photographs, Jing Wang.

Two very colorful envelopes, one for a man, the other for a woman, filled with “clothing in base paper”. The motifs on the envelopes are permeated with lively colors: green, red, yellow, orange, peonies (the empress’s flower, “no longer fashionable”, according to vendors). Hong Kong, 2016.

© photographs, Jing Wang

Life Cycle of Objects and Brand Value

Whether these objects are sober or flashy, transmutation – their “death” in flames – is their inexorable fate. For believers or practitioners of this “cremation”, it is a transformation of existence or a rite of passage, bound for a new life in the afterworld, the world of the gods, “phantoms” and ancestors. The paradox is that this destruction or disappearance of the paper object implements a transformation of its substantiality, its nature and endows it with a presence that transcends the remaining ashes or smoke rising into the sky. Most of these artificial objects are reproductions of “real objects” from people’s daily lives: clothes, dentures, household appliances. They are to accompany and facilitate the material life of those who are “living” henceforth in another world, at the same time both very far and very near. Each object has a “life”. The buyers appropriate them by personalizing the symbolism of the “objects to burn” in line with their individual emotions. Buyers who have an intimate relationship with the shopkeeper might well express their emotions or their wishes freely in order to find the best article matching their feelings and desires.

If the material is very simple and always the same – since it is essentially paper – these “copies” differentiate themselves in several ways: the quality of the pitch paper, the treatment of the surface, the type of printed drawings as well as by their symbolic meaning. These objects, like “lucky charms”, follow social, cultural, and symbolic conventions. The “wings of a windmill” for example, express the immediate families’ well-being, like the image of wind gently and easily rotating the blades of a windmill. These “lucky charms” are for the gods; their protective objective, to prevent the evil spirits from revealing themselves. Offerings are also made to the divinities. Different levels or degrees exist in the art of imitation: a material is “reproduced”, a woolen sweater for example, and patterns can turn into abstract representations. As for lace and buttons – in plastic.

The relationship between the purchase price of a paper object and the symbolic and emotional value associated with it is very complex. The price of paper objects is a tiny fraction of the monetary worth of the imitated article. The final purchase price is linked to the cost of the pitch paper, but also to the artisan’s skills; production time has a “real” cost, especially if rent or workers’ salaries are taken into consideration. In addition, the price of the “real” article in the consumer goods market, for example, the retail value of a real Rolex watch, is not without influence in evaluating the price of the offering, in such a case, the price of the paper printed with the simple motif “Rolex watch”. The same applies to clothing or shoes with labels like Chanel, Gucci…, roughly respecting the markets’ benchmarks. For paper banknotes, using the term “fake money” is inappropriate since these imitations are sold in proportion to the value of the denominations. Furthermore, the monetary value is set once and for all only upon exchange between customer and vendor. It no longer fluctuates with the market because the circulation of a paper object is limited and almost nil in the world of the living: we cannot use, nor resell, nor exchange it for another item.15 On the contrary, in the spirit world of the gods or the ghosts of the dead, according to the principle of transmutation, monetary value of a paper object is equal to that of the real object represented. Thus a printed paper “Rolex watch” has no monetary value for a living person. Yet, in the world of the departed, in the consumer market of the hereafter, it has the same value as a Rolex!

Clothing in cardboard and paper, Hong Kong, collection Jing Wang, 2016.

© photograph, Manuel Charpy.

Clothing in cardboard and paper, Hong Kong, collection Jing Wang, 2016.

© photograph, Manuel Charpy.

Luxury in the Hereafter: the Double Life

The relatively recent success of luxury brand name items in connection with the opening of the capitalist market has nevertheless influenced market value of paper objects and the social issues of offerings by focusing on the ambiguities of the double life of these objects. It cannot be argued that it is only to ensure that the deceased maintain a material life equal to the one they knew, since most of the deceased in question never had access, neither under the communist regime, nor today, to such a life. The issue then is the idea of “really” offering these objects to the deceased, these objects representing the pinnacle of modern consumers’ desires, symbols of prosperity and well-being.

The stakes are high for “brand” logos and designs, both symbolic and emblematic. Gucci, in its warning over the sale of “counterfeit” items using its “label”, quite rightly raised the question of “brand intellectual property“. In a society where we consume also, if not mainly, appearances or pipe dreams, brand names in both senses define worth. Today, the Western media perceives China as a country in which wealth has become almost the sole reference for judging a person’s worth. Luxury products have become indicators not only of financial success, but also significant factors in establishing interpersonal relations. Some “rich” wear t-shirts and trousers stamped with the Gucci logo from head to toe, and in this way affirm, in a conspicuous manner, their control over this code and their buying power.

The symbolic and emotional value attached to the paper object ultimately exceeds its monetary significance. As “mediator”, the paper object transmits the wishes and tribute of the living to the dead and the gods. This is why it is not a simple conversion of symbolic value. The deliberate purchase of a luxury product testifies to the buyer’s esteem towards the receiver. But the alternative choice of a watch or a piece of clothing without a fancy label can attest to the idea of sentiment being privileged and that affection can manifest itself through the object’s low cost. This is a very personal practice to distance oneself from this custom of paper offering that is more and more related to luxury, encouraged by the consumer society.

Family Piety and Promise of Rebirth

A noteworthy fundamental aspect is that the rite of burning paper objects attests to the persistence of a shared “metaphysical” belief concerning what life after death is. The life of a paper object is surely very short compared to the time to manufacture and then reduce it to ashes, but it is quite long with respect to its evolution in the hereafter; it is supposed to exist forever and last for eternity in the ancestral world, as needed objects to “live”. The ritual in which these objects burn and disappear slowly and progressively is a process of transmutation of their lifeworld calling for the respect of certain attitudes. For example, we are not supposed to take our eyes away from the flames while the objects are burning and decomposing into ashes. It should be stressed that the objects must be completely burned up to be sure the ancestors have “completely received” the items. The objects lose their initial morphology, their material shape, but with the promise of their rebirth16 they acquire a beauty, a function, and a brand-new value.

However, such wishes translate into the expectation of a gift-exchange. They attest to a desire for reciprocity formulated by the living addressed to the gods, ancestors or spirits, the request implicit or the explicit expectation to receive protection in exchange. Readings in terms of gift and gift-exchange regarding this “sacrifice” are not lacking. Objects are destroyed and go up in smoke, though there is a fabrication cost and a purchase price, just as, noted by Mauss, in the Western world we allow flowers to fade away or leave purified foods on tombs of the deceased to rot. These are live and real donations to loved ones in the hereafter. The principle is the same: a gift-exchange is elicited from the ancestors and the gods.

We can also refuse to take into account readings in terms of ritual homage, veneration or formal commemoration to the deceased or to those who seek only return on investment and material benefit. In this case, we must refer to anthropologist Janet Scott, who suggests that these paper offerings will endure by fulfilling another purpose: to create and ensure in a concrete fashion, that the hereafter in which the ancestors have been called to reside, exists.

In short, the hereafter does not exist per se and passage into it is not at all automatic; the dead need the devotion, the attention and the care of the living. “In such exchanges” she writes, “the ideology of filial piety takes an authentically concrete form such that the ancestors are provided for by the offerings (which makes Hell less awful). The hereafter is actively created and Hong Kong practitioners are anything but passive in their cult and determination to shape the world of the hereafter.”17 “Practitioners are solicitous about supplying not only a large quantity but also a large variety of materials and providing the latest in terms of technology and fashion in such a way that the world as it was known by the deceased is reproduced in a credible and up-to-date manner.”18

Sweater in paper labeled冥府服装 “clothing for Hells” and 50 yuan banknotes from Hells. Hong Kong, collection Jing Wang, 2016.

© photograph, Manuel Charpy

Consumption, Revolution, and Redemption

The success of luxury product reproductions has aroused a number of reservations and criticisms in modern China in the name of official Communist egalitarian ideology, even if growth, these last decades, has been based on industry and commerce commensurate with a capitalist regime. Conversely, one could be excused for thinking that the production of paper objects affordable to all strata of a population ideally compensates the current inequalities and affords the promise of a reestablishment of equality between the rich and the poor in the hereafter, as does traditional Christian religion narratives, as does communism. On another religious note, since it is very much a question of comfort brought to the deceased to “shorten the time until rebirth”19, it must be noted that the Buddhisation and even more so the Christianisation of traditional beliefs introducing the themes of reincarnation and redemption, is an additional issue in the renewal of offerings and the cultivation of exchanges with the deceased. As Vincent Gossaert remarks, “Supplementing the Confucianist ancestor cult, Buddhism, from its introduction in China, opened the possibility of an additional cult, due to the monk’s intervention. Thanks to them the deceased saw their posthumous fate improved by the merit brought to them. This Buddhist concession to filial piety further increased the duties of the mourners. It has been justified by the intervention of a rather long-time trial in Purgatory, between death and reincarnation, during which the heirs need to support the deceased.”20

The myth making Chinese otherness exotic in the field of spiritual preoccupations, such as the materiality of the unseen, is to be revisited as imitation paper clothing urges us to reenact contemporary material life.21