Yvette Roudy was the first Minister of Women’s Rights (1981-1986) in France. During her ministry, she sponsored several fundamental laws on subjects from access to abortion (the 1982 “loi Roudy” on reimbursement) to gender equality (the 1983 “loi Roudy” on professional equality). She also fought for parity and for the feminization of occupation names (starting a committee presided over by the feminist writer and activist Benoîte Groult in 1984). She worked as a translator, notably for Betty Friedan (The Feminine Mystique, 1964). She also wrote several of her own works, including La femme en marge (1975) and Mais de quo ont-ils peur? (1995).

In an obituary for Benoîte Groult in Le Monde, a journalist wrote that “since adolescence, not only did Benoîte lose interest in her clothing but she actually took initiative to become ugly. As she recalls in Ainsi soit-elle (Grasset, 1975), where she affirms her feminism: “The idea that my future reputation, my success as a human being, depended on the obligation to get a good husband sufficed to transform the pretty little girl that I see in childhood photos into a dour and stubborn adolescent, riddled with acne, pigeon toed, hunchbacked, and with eyes darting away as soon as a man came into view.” What do you think of this? Of the idea of emancipation through “becoming ugly” and rejecting fashion?

I was a friend of Benoîte and I admire her for everything she did, and for her book, Ainsi soit-elle, which had a remarkable popularizing influence. To me, this book is her most important work. She found the words to take something not easily accessible and render it so. Exposing herself in that way was daring, because Benoîte was someone very modest. And in exposing herself she managed to convey very complex concepts. She found the words to transmit them to everyone. So… as to what she said in Ainsi Soit-Elle… I don’t know if the confrontation she talked about was really a preoccupation of feminism, but it’s clear that the act of wearing pants – that I can wear pants and feel good about myself – is a major liberation. I remember the first pants that I wore, when I was very young, during the war. My friends and I at school made a bet that the next day we’d come wearing pants. I came wearing them and the others didn’t – they had skirts on… And I remember that one of our teachers asked me very critically, “you don’t have a skirt?” This to say how much wearing pants was still considered taboo. And even in the wake of the war, it was seldom seen. Pants were a veritable victory. Now some women of my age only feel good in pants and young people wear them a lot.

Is fashion a question for feminists?

Not really. I never saw that subject before me. Or I wanted to ignore it. I thought it was a secondary question. In any case, I only saw clothes as a question of comfort, not a question of ideology. But now it’s becoming a subject – as Christine Bard showed. Even if I think that feminists should act only how they want, without worrying what others think of them. George Sand found the need to dress as a man, and so did Louise Michel – because it was ultimately more practical for them. But fashion, for awhile, was governed by men. And often I find it profoundly ridiculous. Men who dress women that way don’t like them! When you consider fashion runways, no one would leave the house in an outfit like that to take the bus. So in a way we’re prisoners of clothes. In that sense, it’s a real question that feminists must address. Women were for a long time constrained and encumbered by clothes thought up by men… In that sense, again, pants were a formidable victory.

Are there clothes that are forbidden/unthinkable for political battles or on the other hand clothes that are endorsed?

In reality we have a practical relation to clothes: when we go protest in the streets, we need to be able to run. So flat shoes and flexible clothes that don’t hinder running… But that goes for militantes which doesn’t apply to all feminists – some fight with their writing.

Is the question of colors relevant?

No, really, I don’t remember. When we went to protest we didn’t think about that. But today, still, if I need to give a baby shower gift, I’ll be careful to avoid pink if it’s a girl and blue if it’s a boy. To avoid submitting to stereotypes.

Does it make sense to you to say that couturiers liberated women?

There are couturiers who liberated women, but one or two, not more. Most couturiers don’t pay attention to that. Poiret, who contributed to freeing women from the corset, is important. When I was very little, in the 30’s, I was tied up in a corset… But they were dispensed of quickly. Chanel admittedly contributed to liberating women. But otherwise, most designer don’t. They even impede women, though sometimes without doing it explicitly. In the end, much of fashion represents the crushing power men have over women. I’ll even say that the biggest transformational force was history – and particularly the Great War. If you look at styles before 1914 and after the war, they’ve completely changed… Women understood that if they wanted to work and practice “masculine” trades, they needed adaptive clothes that didn’t get in the way. The war liberated women. Also, there was a trend of masculine clothes following the war, like with Madeleine Pelletier, the doctor and psychiatrist… condemned because she performed abortions. She was incarcerated, tormented, and locked up in an asylum. It’s a travesty how she was treated. And she finally died in 1939. This doesn’t go to say that feminists necessarily need to adopt men’s clothes, which I find very severe… And besides, why all that severity in men’s clothes?

Can you tell us about your own history with fashion and the evolution of your wardrobe?

I only changed my approach to colors since I got white hair. I realized that black didn’t fit me that badly after all! So I don’t avoid it anymore, whereas before I wore mostly colors.

Do you have a memory regarding clothes – political and/or personal – that influences the way you dress? Or a dress code against which you built yourself as a feminist?

I lost my mother when I was 12 so… I was a tomboy and very independent… In reality, it’s mostly ideas that led to my political activity. I became a feminist thanks my father, who was unapologetically macho. I was in constant rebellion against him: “why can’t I do what my brother does?” And the response “because he’s a boy” always struck me as lacking… I didn’t accept it and that’s how my feminism was born – intuitively. Afterwards I discovered feminist theory and analysis with Colette Audry. So I can’t say I thought much about clothing. Even if I think that the way we dress is essential. It’s a question of respect for oneself and for others. We must be polished and not renounce a certain elegance. Beauty is important in everything…

Did you have different ways of dressing according to your positions?

What’s sure is that as minister, one could and had to change outfits every day… Which is admittedly satisfying. But you’ve got bad luck with me, I don’t vary my outfits much. I’m very classic!

Have you ever in certain circumstances forbidden yourself certain clothes or outfits?

No, I don’t have examples… As I said, what’s important for me is being polished without shocking; to be at ease in my clothes for what I have to do. And inversely, I never forbid myself pants. But that caused some problems at the Assemblée Nationale because the law forbid pants and I dared to ignore it. That happened often… But all that’s from thirty years ago. Now women are liberated in that regard. That being said, the episode with Cécile Duflot’s dress shows the persistence of certain masculine behaviors that to me are unacceptable. And the way that Édith Cresson was ridiculed and insulted… Today something like would be called defamation. There are laws now that permit women to defend themselves, even if sometime, despite everything, women don’t take advantage of them.

What clothes do you like to wear?

Pants still… And today I don’t like the vest I have on. I would’ve preferred a brighter color [it’s a very pale sky blue]. I have a vest that’s exactly the same but in red and it suits me better! But ultimately what’s important to me is comfort. Comfort transmits through clothing and you must feel at ease in your clothes. I observe a lot of women and the way that they dress these days. There’s the temptation to be “recherché.” This morning I saw the women who went to vote [at the right wing primary]; Nathalie Kosciusko-Morizet came in a skirt and blouse. She was very nice to look at but generally she wears pants because she campaigns. When I used to campaign – which I did a lot; political campaigns, municipal, legislative etc… I had to walk, climb, come and go… You have to be at ease then, to feel good, and that’s only possible in pants or very supple clothes. Like with men, in a way, who never think about those things and take clothes that they feel good in. But to come back to Nathalie Kosciusko-Morizet, I think that she plays with clothes freely. And she’s right to! But I don’t seek the “recherché”… I don’t look for the detail that makes me stand out. I don’t try to distinguish myself with this or that. For me, that’s secondary. But I like refinement in the cut of an outfit for example. And an outfit that’s missing a button or that’s stained in the wrong place can ruin my mood! Since I’m always representing myself in way, I need to feel good about myself.

Can you choose a photo of you for our review and comment on it?

…I don’t know… There are two satiny jackets that I’m particularly fond of, that I wear when I go somewhere (notably a lilac one). I’ll show them to you. I like wearing them with black pants and a white shirt. I like that outfit because, simply, it makes me feel good.

The historian and writer Michelle Perrot’s research extends to topics as diverse as labor and the working class, delinquency and prisons, private life, and women’s history. Her books include Histoire de Chambres (2009), Mélancolie ouvrière (2013) and Des femmes rebelles (2013). She also edited (with George Duby) Histoire des Femmes en Occident: de l’Antiquité à nos jours (1991-1992). She coproduced Lundis de l’Histoire on France Culture radio (1990-2014) and in 2014, she received the Prix Simone de Beauvoir for her work.

What do you think of Benoîte Groult and of the idea of liberation through “becoming ugly” and through disinterest in clothing?

I understand Benoîte Groult’s reaction and her desire to escape the imperative of beauty. “Be pretty and shut up” – we know that old command. A lot of women shared her sentiment. George Sand freed herself from that dictum in her writing and her life. In her autobiography, Story of My Life, she wrote of her old identity as having shriveled up and declared that she wouldn’t return to it. She dressed as a man to run around more freely in Paris, to voyage or to ride on horseback. But she kept a taste for crafts – she dressed puppets at the théâtre de Nohant – and for beautiful fabrics. Also, the philosopher Simone Weil said that she cut off all seduction as a matter of ethics and convenience. There are a lot of other examples. But on the other hand, many women (even feminists!) love ornaments, pretty textiles, beautiful dresses, clothes that transform, that permit one to be another. The taste for dressing-up as an escape, an alternate self. Fashion, as long as it doesn’t constrain – which it did much more in the past – permits these escapes.

Is fashion a question for feminists?

Fashion is surely a question for feminists, in the sense in that it’s part of a system of domination over women’s bodies, their appearance, but also their shape, their movements, their daily schedule. Think of the tyranny imposed on the bourgeoisie of the past. But there are positions besides rejection; one can adapt or invent new fashions. The women’s liberation movement changed fashion and now women don’t tolerate the same constraints.

Is clothing a political weapon?

Clothes – and more broadly, appearance – were forms of political expression many times throughout history. The French Revolution was also a revolution of fashion, with the sans-culottes. For women, we can think of the rejection of the intolerable cage crinoline; of the corset around 1900; of cyclists wearing bloomers as a prelude to shortened skirts during the Belle Époque; of short hair during the “années folles” which were also the years of the pant suits that characterized Garçonnes (cf. Christine Bard and her two books on the subject). Some women shaved their heads after the Liberation of Paris to protest the same being done to women accused of fraternizing with the enemy. Jeans were also a form of emancipation. But liberation can also come through reaffirming femininity, for example with the long gypsy skirts of hippies. Cécile Duflot’s flower dress in the Assenblée Nationale in 2012 was also a way of affirming a feminine style too often reduced to the famous pant suit.

Are there clothes that are forbidden/unthinkable for political battles or on the other hand clothes that are endorsed?

Forbidden clothes? Not really. But there are demands tied to ordinary sexism. The first female politicians felt scrutinized, judged, and obliged to wear neutral clothes that covered their body and even obscured its shape. We have to make people forget that we’re women and not wear anything sexy. Hail the pantsuit and neutral colors that don’t draw attention. Of course that changes with time. Rosine Bachelot’s flashy tailors broke with that drab image. Preferred clothes for political battles on the street or in collectives, surely: the popularization of jeans responds to the desire for liberty and for a practical neutrality. But women are ingenious at bringing a touch of fantasy to them. You can see this throughout the 70’s.

Does it make sense to you to say that couturiers liberated women?

Some designers sensed the needs of women and contributed to liberating them. Poiret, Coco Chanel, Saint-Laurent, Sonia Rykiel… fall into that camp. But there are others, especially since so many female designers have entered the fray of prêt-à-porter in recent years. Beyond politics, it’s undoubtably driven by economics – adapting to the “new woman” who works, drives, travels, plays sports etc…

Are there favored colors for feminist battles or, inversely, forbidden colors?

“Baby colors,” blue and pink were banned for a while. Red and black were preferred. It seems to me that the neutral and somber palette of the first feminists got considerably brighter and richer.

Can you tell us about your own history with fashion and the evolution of your wardrobe?

I have memories regarding clothes that are both domestic and political and that I realize thread through my live. Sometimes in small, incongruent details: the ribbon that I wore in my hair during the exodus of 1940, a certain red blouse that I was told suited me, a big orange coat that I had during my first loves… All this is assuredly more biographical than political.

Do you have a memory regarding clothes – political and/or personal – that influences the way you dress? Or a dress code against which you built yourself as a feminist?

In my childhood and my adolescence, I was caught between contradictory influences. My mother (1895-1995) was a very elegant women, conscious of fashion in a way that raised it to an almost ethical level, in the same category as hygiene. My dad – very 30’s sportsman, of the Great Gatsby type, obsessed with convertibles and horses – loved giving her gifts and went to the best couturiers to buy her chic outfits. This was before the time of mass production. My mom had a couturier who bragged about being the première at Lanvin. Each season had its new trends and we spend a lot of time choosing shapes, colors, and fabrics. I was part of the drama since my mother cared as much about what I wore as what she did. During my adolescence, I wasn’t happy about it. There was the agony of finding the perfect fit. How do I look in this dress? Does it fit me right? I felt a growing remove between the gaze of others on me and my self-image. A desire to escape constraints. But on the other hand, there was religious school – “le Cours” as we called – where I spent the entirety of my schooling. Austerity, for clothing and elsewhere, was reinforced by the war. We sinned through frivolity. Order and sobriety had to be restored. Nuns, who until then had been secularized – in little black dresses with white collars – were thanks to Pétain (!) returned to religious habits with their folds and cornettes. They wanted to put us in marine blue uniforms that revolted my mother. Under the pretext of not finding the right cloth, she chose a slightly different shade of violet blue that caused my torment. I was very conformist and hated standing out. I suffered a lot because one summer I had to wear a striped pastel skirt; it was very pretty but I hated it and found it improper! The war made me a Jansenist, hostile to all frivolity. I started hating visits to the couturier and the drudgery of fittings. I refused a sheath dress that my mother thought necessary: silhouettes were an obsession and I always thought I was too fat. Basically these clothing troubles ruined my life and I dreamed of escaping them. Coincidently Benoîte Groult was giving classes – in Latin or English, I can’t remember – in my girl’s school. I admired her sporty outfits and her felt hats like our idol Danielle Darieux’s. She never knew that she contributed to my fashion liberation (among other liberations), she who wanted to be ugly!

Do you have different outfits according to different circumstances? Have you ever forbidden yourself certain outfits?

I do, in fact, wear different clothes according to circumstances and occasions. I “change” often. At least I used to. Because age blurs things and gives more liberty while loosening social constraints. I don’t have the same obligations. Not the same desires either. I wear the same clothes more often. I’m more indifferent. But have I forbidden myself certain clothes? Yes. I used to be extremely modest and a conformist. I didn’t rebel against the ban on pants in high schools which lasted until the 1970’s. I wore dresses, skirts, stockings – that were always laddered – and tights… All kinds of things that I practically forgot about

What clothes do you like to wear?

Comfortable clothes, jackets, raincoats, pants, all kinds of sweaters. I like mesh, leather, summer linen, scarves to vary colors. I prefer an elegant sporty look. And I appreciate masculine style, which I find more and more elegant. I have few outfits that are really formal and that sometimes causes problems at this or that reception which I sometimes don’t attend because of my ad hoc wardrobe!

Do you like to go shopping?

For a long time I didn’t like to shop. I had a boutique of refined clothes where the owner, Marie Brunon, was very knowledgable, especially about Italian fashion. I always enjoyed choosing my clothes in her intimate and charming store. I appreciated the informed eye of the saleswomen who knew me well and had good advice. And trying on clothes didn’t bother me. It was a nice moment, reassuring despite the long fittings, because of the owner’s indulgence. A nice moment “between women” that I miss now that the boutique has closed. So now again I’m trying out different boutiques in my quarter (the left bank) or in the Marais (magnificent clothes) without displeasure and even with the feeling of discovery. But I’m forming new habits without realizing it. I am decidedly lazy… I also go to Le Bon Marché, especially to the men’s section which I find superb, guided by men in my famille, who get along very well when I’m a bit lost. I like small businesses with already well curated stocks. The abundance of brands and clothes bewilders me. It often happens that I don’t by anything because between different models, I can’t decide. Between designers: Angès b, Ralph Lauren, Prada, Pôles for knitting, Repetto for shoes… But I’m not really focused brands.

Fashion, Clothes, and Feminism Can you choose a photo of yourself for our review and comment on it?

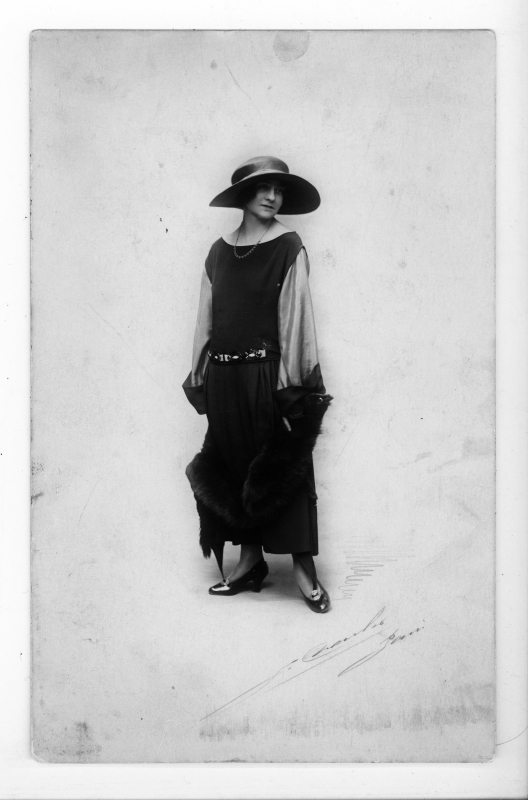

I hate how I look and therefore photos of myself. I have nothing pleasing or pertinent to give you. So instead, a photo of my mother, so pretty in her 1925 outfit.

Interview with Gwladys Bernard, Elody Croullebois, Ophélie Latil, and Aurélie Louchart; all activists in the Gergeotte Sand feminist collective. They define its sociological characteristics as follows: “The typical profile, even if we want it to change, is white middle class women, 25-35, heterosexual, and with a higher education.

What do you think of Benoîte Groult and of the idea of liberation through “becoming ugly” and through disinterest in clothing?

Elody Croullebois: We talked about it the other day. We agreed that it was reductive because, in the end, in acting that we she still inscribed herself in relation to the male gaze. And two pages later, Benoîte Groult synthesizes it very well herself: “When I became a feminist? I didn’t even realize. It happened much later, and undoubtedly because I had a lot of trouble in becoming feminine. All the paralyzing fears of my youth – of not fitting into imposed definitions and not finding a man – came back to me when I saw my three young girls and their liberty. Life hasn’t become easier for them, of course. Liberty is not easy for oneself and even less for others. But at least the problems they face aren’t tied to that exasperating definition of a “real woman” outside which one is ostracized and that enacts its ravages still today.” Emancipation is in doing what we really want to do.

Aurélie Louchart: I would add a counterpoint though. It’s difficult as a woman to renounce the conditioning of wanting to be desirable. There’s always an imperative to be pretty, or at least, to make an effort to be. There’s also pressure to find a partner. To not be desirable is to risk being alone. We can’t dress exactly how we want or we risk paying a heavy price. What’s essential to me is to be conscious of what’s in play. One can be very liberated in a mini-skirt or, on the other hand, very alienated; the same with the veil.

Ophélie Latil: The idea that Benoîte Groult evokes of making oneself uglier is not the solution. But it also comes from another generation of feminism. My mother, who was very coquette while simultaneously going to lesbian squats where she burned bras, told me that when she came well dressed to feminist meetings, she was asked “you’re feminist while dressing well like that?” I got similar reactions ten years ago when I started being politically active and arrived in high heels at a protest or a squat. But real emancipation comes rather with a relation to oneself and to the complexes that we all internalize. I have the impression that before, the complex was to not have found a man. Now it’s to not have a size 34 waist.

AL: Before what was forbidden was to use one’s body; now it’s to not do everything to have a perfect appearance. But to not put on lipstick or not wear heels because it wouldn’t be feminist is still to place oneself in relation to men.

OL: The notion of pleasure is important too. There’s a pleasure, a sensuality, in putting on pretty lipstick or heels. And an aspect of Proust’s madeleine: to put on makeup, blush, the touch of the brush on my cheeks sends me back to watching my grandmother in front of her mirror.

Gwladys Bernard: I had a phase of making myself uglier, at least in the manifest disinterest in appearances, between ages 15 and 23. It wasn’t based on the male gaze, it was more about wanting to do well in my studies, and I had the feeling that shopping and trying to make myself look pretty was a waste of time. I considered fashion as futile and image as a trap. It was a kind of reaction to what my mother lived through; she stopped her studies very early and lived the high life with stylish socialites. I had badly dressed women has role models. My model was Martine Aubry, not Sharon Stone. I wanted to be neutral. The only leeway that I allowed myself was with costumes, which I wore (with pleasure) for dance and theater. The change came when I realized that fashion was a relation with oneself and not a social straightjacket.

Is fashion a question for feminists?

All together: Yes!

GB: In one sentence: fashion is political, feminism is political.

EC: I won’t say that it’s an “official” question at Georgette Sand, which has a more cross-sectional approach, notably on economic rights and stereotypes. It is more in other movements, like of course Femen who often use nudity as a tool in their protests. But at Georgette we talk about it a lot, and we don’t always agree on the answers, leading to debates like the infamous “thong or panties?” which became a joke between us (is wearing a thong a form of alienation?)

OL: Or on the hypersexualization of certain stars like Beyoncé, Rihanna, or Miley Cyrus. Unlike the other two, Beyoncé’s hypersexualization seems to come from a form of empowerment, because she accompanies it with feminist discourse; she’s an ambassador of feminism; she controls her image and built a business. That’s not the case with Rihanna or Miley Cyrus where you can feel a real fragility. But we’re always debating this!

AL: Basically we argue about these questions but we don’t want to publicly communicate them because we don’t want to put ourself in situations of forwarding the right or wrong answers. At the end of it all, we really stand for personal liberty. Still, the work feminists need to do against the tyranny of beauty seems to me essential, if only for the question of the objectification of women. A number of studies show the link between that and nutrition problems or depression.

GB: I looked at the Institut Émilie du Châtelet where the average age is higher, around 50. None of their conferences or meetings were dedicated to that theme. It’s another generation, for which fashion is not a serious subject.

Are clothes a political weapon?

AL: Yes, they can be a real tool in the struggle. Appearances and clothes are stakes in the “culture wars”; they’re symbols that can be manipulated.

OL: You only have to look at the Manif pour tous with their Phrygien caps (also taken up by Melanchon by the way!) or the adoptive uniform of feminine antifeminist movements like Les Cariatides or Antigone, with their white dresses. At Georgette we have a symbol, or rather a sign of recognition: a little green or violet bow. We chose it when we started the collective because our goal was to deconstruct gender stereotypes. We went off the idea that certain attitudes and objects are synonymous with power when associated with men but their connotations are inverted when associated with women. That’s true with bows: a bowtie on a man is elegant, serious, a social marking. Bows on women, especially in their hair, are signs of frivolity and superficiality; they read “little girl.” In adopting it, we wanted to convey the differences in representation between men and women. The men of our collective often wear it in their hair!

Are there clothes that are forbidden/unthinkable for political battles or on the other hand clothes that are endorsed?

EC: No, and there shouldn’t be. Clothes that work for the fight are ones that make us feel good.

OL: I make it a point of honor to be well dressed for protests. Precisely because I know it’s not the stereotype of us. We know now that feminists have a sexuality, that they’re not all bitter and humorless, but there’s still the image that they’re badly dressed, whereas I love to dress well.

AL: In the past I censored myself a lot, especially for protests. I told myself that I couldn’t wear this or that, that I would lose credibility. Now I’ve confronted that fear. I’ve told myself that we must do what’s not expected of us. To wear pink – why not? We can reverse the negative connotation of what’s “girly.” It’s about breaking through constraints to open the field of possibilities; to refuse to be shut in.

OL: In any case, it’s the fact of being a women that makes it that we’re not taken seriously, not dressing in such and such a way. What’s “problematic” is simply having a vagina! Not wearing pink, dressing in black, being disagreeable – that’s the old method, of our mothers. I maintain that if I’m dressed in pink with unicorns on my shoes and if my speech proves competent, I must be heard.

AL: In any case, clothes don’t protect against sexism, or racism! However we dress, a sexist man will consider us inferior simply because we’re women.

OL: That’s for sure. I have a memory of walking down the street behind an American in short shorts; I was wearing a long, flowing skirt with a somewhat tight-fitting top and next to me was a girl in a veil. Well we all got whistled at and catcalled with the same remarks. It wasn’t our clothes but our status as women that was in play.

Are there favored colors for feminist battles, or inversely, forbidden colors?

All together: No, no color is forbidden.

OL: The green and violet of our bows are the colors of the suffragettes. We really situated ourselves in a tradition when making that choice. And pink is still an issue. We did in fact do a lot of work on gendered marketing with the Georgettes. But we didn’t want to categorically reject the color’s girly side and all that it implies in terms of “cuteness.” I didn’t have the right to wear pink when I was young; my mom wouldn’t let me. I finally earned the right to have a pink pen in 5th grade, after five years of negotiations.

AL: Do you think that we’ll be like that too?

Does it make sense to you to say that designers liberated women’s bodies?

GB: Don’t liberate us, we’ll take care if it! I already have a hard time with the idea of male designers liberating women. As for women, I think immediately of Chanel and Madeleine Vionnet regarding the corset. I’ll say that there are certain liberating aesthetic choices, but afterwards it’s women who liberate themselves. You can have women dressed in Chanel who are the incarnation of misogyny!

OL: And after all, Chanel created corsetless dresses that necessitated being very skinny. That’s another form of constraint on the body. Was it feminist then? For her, yes, but for others? On the other hand, Gaultier had a runway with models who weren’t skinny.

GB: But despite everything, that’s an exception. When you read the autobiographies of models, it makes you scared. Feminists ask questions about fashion but feminism doesn’t seem to be a question in the fashion world or with costumers. The major costumers are mostly men. I’ve heard remarks that show a complete lack or respect for the body, like “your breasts, I don’t care, put them where you want” as the guy crushes you into a XVIth century style corset where you can’t breathe. It’s completely ruthless; a world of seamstresses who are often mistreated.

OL: One of the rare times that I worked with high-fashion costumes, was at the Aix-en-Provence festival d’art lyrique. Costumes by Issey Miyake if I remember; very classy. Men had big, gauzy pants that were very fluid; magnificent. We had shoes that compressed our feet – we had bloody feet every night – and wrap-around skirts that didn’t stay up. Everything was thought up around the men, not the girls, who were in a state of incredible discomfort, especially in the July heat. It didn’t correspond to female bodies or to the weather. You really saw that it was a man who thought up the costumes.

AL: Yes, and indeed fashion is still largely determined by men. It’s mostly créateurs and not créatrices.

EC: There’s starting to be a recognition of the diversity of bodies in runways (let’s hope that it’s not in the end just a matter of what’s in vogue!) But there’s still a lot to do, especially when we see ad campaigns like American Apparel’s which put 15 year old girls in suggestive poses that I find scandalous.

AL: This all reverts to the problem of the tyranny of beauty in our occidental societies in the XXIst century that the novelist Nelly Arcan called “the burka of skin” (an echo to Eliette Abecassis’ “invisible corset”). The fashion world has a responsibility, especially regarding the choice of models, and even more concerning Photoshop retouching. A study was carried out with adolescents in England that showed that a large majority of girls knew that fashion photos were retouched but that didn’t stop them from having painful complexes. This remains then a subject for feminists.

Can you tell us about your own history with fashion and the evolution of your wardrobe? Do you have a memory regarding clothes – personal and/or political – that influences the way you dress?

GB: My history with fashion doesn’t correspond to fashion trends. I don’t know them. I don’t know which colors are in this season and I don’t read women’s magazines. The evolution of my style is more linked with my personal trajectory. I started dressing differently since I became an activist. Now I have an emancipated wardrobe. I let myself wear things that I would have only worn on stage: a lot of velvet (which I love), a bit of fur despite the protests of my vegan friends, colors, clothes that are “outdated,” clothes of all different forms. In the “La Barbe!” collective that I’m also active in, I was more careful at first because the movement (mostly lesbian) has a more “queer” style. But now I dress how I want. La Barbe’s dress code for its protests has changed too: at the beginning the idea was to take the codes of men of the IIIrd Republic, but then the activists saw that it was just as forceful, if not more so, to wear more current clothes and even dresses and skirts.

EC: Until I was about 15, I was more of a tomboy, with big sweatpants and sneakers. I dressed with clothes from the men’s sports section. Around 15, I had a complete reversal and took the look of a 40-year-old woman, with pointed heels and a short haircut that made me look older. It wasn’t sexualized, it was just had nothing to do with current fashions. There were influences from 1920s styles, notably the flapper scarfs that I wore on my head. In photos from this time, I really stick out from my friends like a sore thumb. Then around 17-18, I started dressing more my age. Since 3 or 4 years ago, I often wear skirts. I also put on very high heels, even though I’m already pretty tall (1.7 m). They make me even taller and give me confidence since I see people raise their heads to talk to me. Also – and this is my grandmother’s influence since she had a lingerie boutique – I love pretty underwear. In my family – which is really a family of women – we give each other pretty lingerie, without it being sexualized. It really is my guilty pleasure.

AL: As for me, it’s the fact of having grown up in Seine-Saint-Denis that influenced my wardrobe. I didn’t at all feel free to wear what I wanted. Of course, there was the awkwardness of adolescence, but also some remarks from friends with a clear definition of what a “good girl” was. The predominant fear was that something would happen if I came home late wearing certain clothes. From that point of view, coming to Paris was very liberating. I could put on micro-skirts if I wanted! But I always have ambivalent feelings regarding the imperative to fit into the “feminine ideal.” I felt a need to always be desirable. Until I was 30, I was persuaded that if I put on flannel pajamas instead of a nighty, my man would run away… It took time to rid myself of that integrated alienation. Today I can wear whatever type of clothes I choose, according to my wants.

OL: I have very strong memories of my childhood. My brother asked my mom for those sweatpants with metal buttons on the side of the leg, which my mom refused to buy. She even pulled out an article by Jean-Paul Gaultier explaining that you shouldn’t embarrass yourself in front of the judgment of others. Since that didn’t managed to convince him, one day at the market she put the wicker basket on his head and went stand to stand explaining the situation to alarmed vendors. She got a lot of approval; they congratulated her. My brother was red with embarrassment but from afar I admit a lot of admiration for her having dared that. If we stopped judging people on appearances, it would be a big feminist victory.

EC: Or at least if we aimed for understanding people beyond our first judgements.

GB: Basically our evolutions happened based on our activism or our romantic life, seldom in accordance to fashions. Even if this of course happened in tune with the times, if not based on storefront displays.

Do you have different outfits according to circumstances? Have you ever forbidden yourself certain outfits?

OL: ISometimes I’ll censor myself. Today I had a professional meeting and I put on darker clothes, heels, and a sweater over my somewhat see-through lace shirt. The professional world has its own codes; it’s hard to navigate. And when I was at Science Po, I’d sometimes change my outfit between two oral exams – a more Marie-Chantal style outfit for the civil law orals, and a little bio cotton sweater and a coral belt for the sociology orals.

GB: When I was practicing for my college interviews, one of my mentors told me, “you don’t get it, you’re coming across too competitive. Be ugly and nice.” So I made myself uglier – black pants, black jacket, tight bun, glasses (which I don’t usually wear) and even a shawl. In the evening, on the station platform, my mom didn’t even recognize me. I disguised myself and it gave me confidence. I told myself that it was the outfit speaking.

EC: It’s been more than four years that I’m at the same company, and the ambiance is very nice. Until recently I permitted myself pretty much anything in terms of wardrobe. I had the same kinds of clothes for work as for the weekend. One day I was having drinks after work with friends, one of whom was also a colleague. Someone was surprised at the sexy aspect of my work clothes and asked me if it didn’t have negative effects. I responded no, but I saw my colleague frown. He told me that he’d already witnessed a few shocked looks from management. Since then I’m more careful with what I wear, to not hinder my career. On a more personal level, for Tindr style blind dates I avoid high heels for the first date because I know if the guy’s not very tall, it can make him nervous. It’s a concession for someone who’s fighting against gender stereotypes, I know!

What clothes do you like to wear?

AL: Whatever makes me feel most myself. It depends on the moment and on the mood.

OL: Lingerie, high heels, skirts (I almost never wear pants and skirts correspond more to my body shape and are more practical in my daily life). I don’t hesitate to wear low necklines. We show our breasts at home after all! And I love the boots [black velvet, with fringes, and a small heel] that I’m wearing today – they go well with so many things, adapt to every context, and are super comfortable – they’re like my security blanket! I also have a particular affection for my grandfather’s bowties, which I wear on occasion. Also, the clothes that I wear for activism – like when I did “Super-Précaire” at the European Parliament – help me take command of my body via transgression. Inversely, for awhile I’ve struggled with the kimono that I wear for aikido. It’s ugly. But I’m starting to ignore that, and in the end it allows me a sort of liberation.

GB: For awhile it was costumes. Around 8-9 I had my period of revolutionary costumes and Les Misérables. And dance tutus and leotards. My grandmother often made my costumes. She was trained as a costumer even if she didn’t practice it. I also gladly wore crinolines and wigs. Today in my daily life I’ve kept a few unusual pieces that I have a lot of affection for – a red velvet martial frock-coat, a hat.

Do you like to go shopping?

EC: It’s not one of my passions, and depends on my mood. Most often it depresses me, because I have the impression that nothing fits me or that I’m fat and ugly. On the other hand I love to get clothes from friend. I like the idea of wearing something that belongs to someone dear to me. But yesterday I fell after coming two inches from being run over and tore a hole in my friend’s pants. I was so sad that I still haven’t told her.

OL: Me too, it depends on the days. I have a hard time with how some brands sizes their clothes, like Abercrombie which doesn’t go over size 38 to attract a young, skinny, rich clientele. Also, having worked in the NGO world, I avoid buying clothes made by underpaid women in Bangladesh. That’s why I like buying used clothes.

GB: I’ve mostly hated it and even today it’s not my favorite. Mostly, clothes come to me, through the internet or because something catches my eye while buying my bread or something. I rarely buy clothes. I get them from my mom, my cousins, my aunts. I often ask for clothes as presents.

Are there designers whose work you particularly like?

EC, OL and AL: Yes, there are designers and brands whose clothes we like, but we don’t want to publicly valorize their work while they often offer nothing in regards to ethics or feminism!

Are there women who you admire for their allure, appearance, or style?

EC: In my family, from a body shape point of view, the model was more Marilyn than Audrey Hepburn. But today I have a hard time answering that question since that’s not how I judge my role models. One of the most inspiring models that I’ve met, ideology aside, at an internship in Areva, was Anne Lauvergeon. She has a lot of charisma and confidence; she confronts men and succeeds. She really is incredible.

OL: I love the transgressive use of clothes and appearances with women like George Sand or Alexandra David-Néel (who stole her mother’s wedding ring to be able to voyage alone!) As a kid, I had very few external female role models. I would more often gravitate towards masculine ones (musketeers for instance) without any problems connecting for that matter. But the women of my family were models – very strong, beautiful, in charge of their lives, jobs, and marriages.

AL: Chimandanda Ngozi Adiche. She’s a sublime novelist. And she puts on really pretty clothes, shoes, and lipstick, and owns it. We shouldn’t have to conceal that we like “feminine” things to maintain credibility; as if interest in fashion was synonymous with the absence of a brain… Her speech on the subject helped me and made me think.

GB: I had trouble thinking of an example, but I’d say Colette whose works I’d read and enjoyed before I saw photos of her. I find that she has such an allure, at all ages. And I’d also note that we’ve all talked about our mothers and grandmothers, as models or as foils. They’re our main references in terms of femininity and thus clothes and appearances. And it’s even more complex when you’ve had a feminist and activist mother rejecting what she considered feminine!