In the 19th century, working men were a familiar sight in the streets of Paris, an industrial city prone to riots. Journalists, artists, policemen and statesmen all thought they could recognize workers by their appearance, i.e. by their blouse, a long overgarment of plain-woven cloth that fell to the knees. The memory of the blouse has survived to the present day, albeit vaguely, despite the emergence at the turn of the century of “bleus de travail”, a very different type of French work-wear, consisting at the time of a pair of trousers and a fitted jacket. The identifi-ation of working folk by their blouse followed the practice – so common in the past and the present as well – of designating a social category other than one’s own by means of a vestimentary attribute and assigning a particular term to it.

But the blouse’s reputation as a norm in its day must be compared with the actual vestimentary practices of workers, and that is our main intention. Yes, workers wore blouses, but did all workers wear them? Did they wear them every day? What did they wear while working? These are formidable questions, because while our sources shed a bright light on some aspects of this vestimentary history, they leave many others in the dark. For this reason, our discussion will bear exclusively on the working man: there is no garment equivalent to the man’s blouse that is automatically associated with the working woman and could guide us. Nevertheless, the case seems clear: it would appear that, over the course of the century, the suit, whether for everyday or dress wear, progressively replaced the blouse among Parisian working men, with the “Sunday best” suit figuring as the earliest manifestation of this shift1. We will not be challenging the accuracy of these facts, but would like to highlight the nonlinear nature, the contradictions and the complexity of this decades-long shift. In particular, we aim to prove that the vestimentary norms in use among workers, although conditioned by occupational practices and limited by material resources, were not imposed by externalities, but dictated by values specific to workers themselves.

The blouse, from barricade to metaphor

We are not aware of any representation or written allusion to the working man’s blouse antedating the year 1830 and, more specifically, the barricades of the July Revolution in Paris. It’s as if it took an uprising for the blouse to win recognition among its contemporaries, as if the struggle had opened their eyes. A few blouses figure in heroic accounts published after these events, including the “intrepid fellow wearing a blue blouse and holding a pistol,” whose boldness supposedly prompted the insurgents to take the Louvre2. One eye-witness reported having seen, early in the rebellion, troops emerge onto Place de la Bourse led by “a man whose trousers and blouse of white, plain-woven cloth […] marked him as a mason”3. But the most striking revelation of the blouse is a figure in the painting Liberty Leading the People by Delacroix, executed shortly after these events. It shows a man lying on the ground, the only protagonist in the painting to contemplate the apparition of a woman warrior brandishing the tricolor flag, whose hues are repeated in his clothing: a blue blouse, riding up to reveal a white shirt, and a red waistband. The artist painted him in the clothes of a real working man, a foot soldier of Liberty4.

After 1830, the blouse became a social marker. From then on, people noticed it and called it by name. According to the archeologist Charles Lenormant, wearing the blouse was none other than a remote Gallic custom that had been perpetuated in Auvergne and, in the space of one generation, had made its way, village by village, to the capital:

“First, it became the outfit worn universally by cart drivers. From the roads, it reached the farms. From the fields, it invaded cities, and many industrial occupations have already re-adopted it under our very eyes.”5

The police and the courts, busy repressing civil disorder and attacks during the July Monarchy, never failed to mention it when an accused wrongdoer wore a blouse, wishing to stress that they were dealing with a worker, a dangerous character. During the big strikes of the summer of 1840, the Préfet de Police became alarmed over the groups of “men in blouses” and “juveniles” hanging around at night at Porte Saint-Denis and Porte Saint-Martin6. The “invention” of the blouse as a social marker was followed by an extraordinary inflation in the use of the word in 1848. During the tumultuous months following the popular victory in February, “blouses” were everywhere... in the press, in speeches, on posters, on stage and so forth. More than a style trend, it served to bow at the altar of suffering fellow men, i.e. workers. Louis Reybaud, an economist and social satirist, made fun of these ostentatious and largely hypocritical professions of faith proclaiming an undying love of the working man. “Others went even further,” he added. “They donned the blouse, convinced that they were of the people, because they wore the same clothes. Singular times! Strange ways!”7 As a matter of fact, Baudelaire took to the streets “wearing a worker’s smock” to sell Le Salut public, the newspaper that he had founded in February8.

Of course, there were plenty of real blouse-wearing workers to be found in Paris. In early June, Victor Delente, a veteran of republican struggles, wrote in his newspaper Le Tocsin des travailleurs9, that reaction was threatening to take over the Republic. He noted that, at the legislative assembly, “the blouse is so rare that it seems to stand out like a sore thumb,” whereas in February it had been “the uniform on the barricades”. The desire to be in unison with workers inspired the Montagnards – an improvised company of guards set up by Marc Caussidière, a democrat who served briefly as Préfet de Police – to wear “a blue work shirt and red waistband”10. But donning this “uniform” would eventually backfire for its wearers. During the “June Days” uprising of 1848, the blouse ceased being “the most stylish, decent and wearable of clothes” to become “the mark of Cain” eliciting “a sentiment of horror and hate”11. And this wasn’t simply a manner of speaking. For the custodians of the bourgeois order, every blouse-wearer was a worker and every worker was an insurgent. These misassociations led to a number of summary arrests and executions, such as that reported by an eyewitness, Louis Ménard:

“On Quai des Tuileries, soldiers from national guard units from outside Paris spotted a man wearing a blouse, arrested him and wanted to shoot him. A member of the lower house snatched the man away and tried to explain that some men in Paris wore blouses but were not insurgents, but no sooner had he left than the man was seized again and shot.”12

Whether adulated or abhorred, the blouse had become not only a sign understood by all, but an entity, a way of referring to class antagonism. The expression “les blouses” took on its full force when coupled with another term, “les habits”, referring to well-dressed bourgeois in their frock coats of fine wool13. On a day in May 1848, several hundred actors, artists, bank employees and shop clerks demanded admittance to the national workshops that had been opened by the government to occupy the unemployed. They claimed that they had previously been turned away “because we wore suits and it went sorely against our habits to don the blouse,” but that they, “like the workers,” were worthy of the Republic’s consideration.14 Amid street fighters, “les habits” designated the democratic or socialist-minded bourgeois that had espoused the workers’ cause and were pulling up paving stones alongside “les blouses.” De Maupas, the Préfet de Police at the time of the coup on December 2, 1851, wrote that, on December 3, he had had hostile groups dispersed on Place de la Bourse, subsequent to which “the black suits headed for other points along the boulevards […] to start new demonstrations and the blouse-wearers made for the Saint-Martin area, where they knew they would meet the bulk of their friends”15. At that same moment, a student named Chassin, encountering the barricades erected in rue du Temple, felt full of hope: “Fine wool suits are still dominant, but mingled with them are the blouses of real workers”16. The barricades would be either be mingled or they would not exist at all.

The labels “les habits” and “les blouses” would continue to be used to designate bourgeois and workers, thought to oppose each other in every way, engaged in a class war. Journalist and author Jules Vallès constantly dwelled on the opposition between “men in frock coats” and “men in blouses”17.

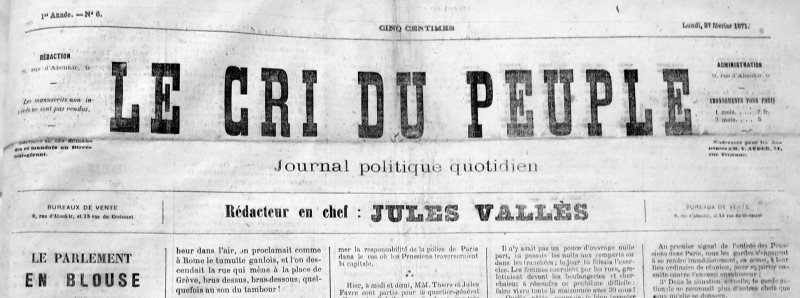

Jules Vallès wrote this well-known article, Le Parlement en blouse, about 6 de la place de la Corderie-du-Temple, where the International Association of Workers and the Federation of Trade Unions had their headquarters on the fourth floor. Vallès wrote: "The Revolution is sitting on the benches, standing back to the wall, hands gripping the podium! The Revolution in workers' garb! […] All hail the new Parliament!"

Le Cri du Peuple (p. 150 éd. française) A news headline dated February 27, 1871.

We could cite many other examples of political and militant texts using this vestimentary metaphor into the 1880s. However, this figure of speech failed to account for the diversity of workers’ vestimentary practices and their own feel-ings about their mode of dress.

The duality of vestimentary practices

The identification of working people with the blouse, in terms of language and imagery, clearly indicates that the blouse was a frequent sight in crowds of passersby and rioters. But where did the blouse come from? Which workers wore it – or did not wear it – and for what purposes?

The origin of the blouse in Paris is not known. What we do know is that it came into use at the turn of the century. Neither the workers shown in the plates of L’Encyclopédie, the last edition of which was published in 1772, nor street vendors18, wore blouses. One pedestrian in Paris, the writer Louis-Sébastien Mercier, mentioned the “people’s motley garb,” but that doesn’t get us very far19. Daniel Roche, in his long chapter on what the people of Paris wore during the 18th century, says nothing about the blouse. This item of clothing was simply unknown at the time20. One obvious supposition is that the blouse worn in Paris derived from the country peasant’s blouse. The latter supposedly originated in the application of “bleu populaire”, a cheap dye made from indigo, to plain cotton or mixed fabrics, long used in many French regions to make garments for work or long wear, such as the blouse21. Was the worker’s blouse the urban version of the peasant’s work blouse, which was usually blue22? At any rate, in the 19th century, the word “blouse” would retain a certain ambiguity due to the bastard origins of the garment itself. The first known representations of the blouse in Paris, whether on stage or in writing – prior to its revelation in 1830 – were of the peasant’s blouse23. In 1880, Jules Vallès wrote Les blouses, a serialized novel inspired by a dramatic 1847 uprising in the town of Buzançais: in this case, the insurgents were country folk24. Mention might be made, too, of the blouse-wearing MP Christophe Thivrier, who became the talk of the town when he took his seat in the lower house – having been elected as a socialist at Commentry in 1889 – wearing a fine blue blouse, like a “rustic”25. With the blouse, had the country come to Paris?

The answer is no. Blouse-wearers in Paris were not always country folk having migrated to Paris for the building season to ply their trowels on construction sites, far from it. The well-known masons from Limousin are the first to come to mind26. Granted, masons wore blouses, white blouses, as one can see in the drawing by Henry Monnier. This was also the outfit worn by house painters, according the following allusion to a crowd of workers standing around the Paris City Hall in hopes of being hired: the workers were “dressed in white trousers and blouses of the same color”27. They wore white... unless they wore blue, as Pierre Vinçard, a dependable guide to the world of the Parisian working man, asserted in 1849 in describing the typical outfit worn by the house painter:

“There’s nothing so picturesque, yet nothing simpler: his work garments consist of trousers of whitish cloth that he dons at the workshop to protect the pants that he wears underneath, a blue work shirt and a large cap of striped cotton.”28

It should be noted, however, that house painters were not seasonal workers, nor was their blouse an item of rustic garb. Furthermore, not all construction workers wore the blouse. Vinçard reported that many carpenters habitually wore “a corduroy jacket and trousers, earrings, a compass in the right-hand pocket and a wide-brimmed hat”29. Throughout this century of major projects in Paris, where works were underway on a nearly continuous basis, the mason’s or painter’s blouse and the carpenter’s corduroys were a common sight in the street. But we have yet to mention an essential fact: the blouse was also a work garment worn in ateliers and factories. While very little is known about this particular aspect of the history of labor, there can be no doubt that certain workers wore the blouse to work. This might seem surprising, given the presence of machines and the unsafe working conditions of the day. Adolphe Boyer, a worker and thinker, denounced the hazards represented by the crowded work spaces at industrial establishments, especially those that were mechanized:

“Step carefully in walking these narrow aisles! Make sure not to get dizzy! For if you trip and your clothes are caught in the gears, you will infallibly be dragged between them and ground or crushed by huge cylinders! This happens all too often to workers or apprentices, caught by their work blouse.”30

The Mason

Alain Faure Taken from Les industriels, métiers et professions en France, avec cent dessins par Henry Monnier by Émile de La Bédollierre (Paris, Veuve Louis Janet, 1842, 231 p.). In the chapter on masons, one reads: “Go out very early, at six o'clock in summer and eight o'clock in winter. Head for a house under construction which – thank God! – is not a rare sight in Paris. You'll see a regiment of workers arriving from every direction, wearing a blue or white blouse for some; a coarse canvas jacket for others; with one pocket bulging with a packet of tobacco, a well-seasoned pipe (usually clay) and a red-checked cotton handkerchief; trousers of blue plain-woven cloth or cottonnade; enormous, sturdy shoes into which not even the lowly stocking is admitted. The outfit is topped off with a wool cap or an item of headgear that one suspects to be a hat beneath all the flecks of diluted plaster or yellow mud left by stone-cutting. This item is also deformed by taps on the head given in friendship or anger.”

Engraving by Chevauchet after a drawing by Henry Monnier.

So why did workers choose to wear the blouse? For the sake of convenience, in spite of the hazard? Because it was cheap? Was it a matter of imitation? Did working class spirit have its own dress code?

Whatever the reason, the “mason from Limousin” phenomenon falls short as an explanation, because not all construction workers wore the blouse and not all blouse-wearers worked in the construction sector. The working man painted by Delacroix was an “ordinary” worker. How is it that the blouse was flaunted by some and ignored by others? To make progress on this point, we need to ask ourselves what workers wore outside working hours, what clothes they wore to go out or for Sundays and holidays... There can only be two reasons for donning the blouse at all times, whether on the job or out on the town: poverty or pride.

Poverty. Over and over again, workers said: “It’s all I’ve got to wear.” The only wardrobe that a worker could ever hope to own consisted of “a very poor hat, two blouses, two pairs of cotton trousers, two shirts and one poor pair of shoes”31. Poverty was so severe that, according to tailors in 1848, some workers made do with a plain blouse when they went out and “went barefoot”32. Leather workers in 1867 observed that renewing their wardrobe was out of the question: “[owning] a single item of clothing is the only way to balance [our] low budget”... and it is not hard to guess what that item would be33. And poverty was attended by all sorts of humiliations. Norbert Truquin, a worker visiting in Paris in 1848, wrote that he could only visit the city’s museums and monuments when dressed in a frock coat “because people wearing blouses were not permitted to enter”34. Proper attire was required. And then there was pride: “I am a worker and wear working man’s clothes.”

Reports attesting this sentiment came later and were indirect. English worker delegates to the 1867 international exposition in Paris often expressed astonishment at the sight of their Parisian brothers wearing the blouse in the street or at an open-air concert at Les Tuileries:

“Our London workman (myself included) would feel ashamed to go into society unless he could wear a suit similar in appearance to his employer [...], but the Parisian I met with everywhere would be attired in a good pair of black trousers and vest, with a watch in his pocket, over this a clean blouse, and a cap, evidently proud to own himself one of the wage class.”35

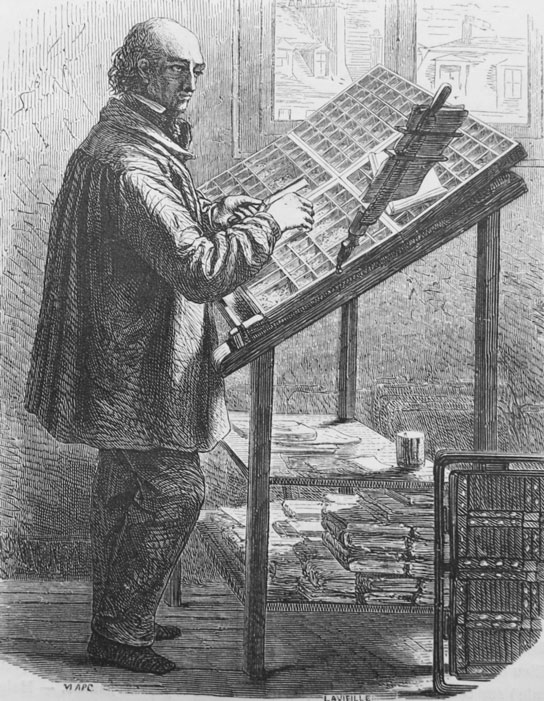

The typography worker

Engraving taken from Théotiste Lefevre’s book Guide pratique du compositeur d’imprimerie, Paris, Firmin Didot, 1872-1873, vol. 1, p. 3 (first edition in 1855).

Living in exile in London, Jules Vallès was surprised to see that “artisans” did not wear blouses, attributing this to misplaced pride. “They don’t wear blues. When they pass you in the street, you’d never know that they are workers.” On a different note, we might quote Denis Poulot, an employer observing worker mores, who denounced certain workers that “flaunted the blouse,” proof of what he called “Sublimism”, i.e. arrogance and class hatred.

“In an omnibus, wagon or public vehicle, if you see a character who thinks he’s entitled to be rude and answers your timid observations by retorting: ’It’s because I’m wearing a blouse or not wearing gloves!’[then you are dealing with a] sublime worker!”36

But pride could take other forms as well. A worker could have a mixed wardrobe, i.e. a blouse for everyday wear and a special outfit for dress occasions. Some workers even had a reputation for being real dandies, such as the qualified tailor, who never went out without their white vest and black suit37! For initiation ceremonies, the master artisans belonging to “Devoirs du Tour de France” guilds all wore dress coats or frock coats38. The joiner Agricol Perdiguier, a joiner and public figure of the day, recommended that workers avoid wearing the blouse for it was always “dark” and “dirty”, placing workers in “a separate class” and “subalterizing” them39. He encouraged them to wear “dress clothes”, an expression used by the activist bookbinder Victor Wynants40 in discussing the admission fee to the 1855 international exposition in Paris, initially lowered to 20 centimes on Sundays to attract workers41:

“Workers attended in dress clothes. It was only their right to do so. Didn’t this event celebrate products that they manufactured? But no doubt too many workers came, or perhaps the organizers responsible for assessing the effect of this measure did not see enough blouses. A new order soon shifted the lower rate from Sunday to Monday on the pretext that workers had not taken advantage of this so-called “favor”. To do so, they’d have had to take a day off from work in order to visit on Monday!”

In other words, the organizers were convinced that any visitor not wearing a blouse had to be a bourgeois, whereas a great many workers had made a point of wearing their Sunday best to the exposition. This vestimentary misunderstanding was rooted in disdain.

From this time on, many workers owned two sets of clothing. A carpenter in 1846 drew up a detailed budget for a married friend that owned “work objects” (work pants and work shirts, but no jacket) and “dress objects” (including a frock coat and an elegant hat)42. Ten years later, one of the first monographs by the economist Le Play, focusing specifically on a carpenter, mentioned his “work garments” (consisting mainly of three work shirts) and his “Sunday best” (a winter coat of fine black wool, fine wool pants and a black silk hat as well as a “blue suit,” worn only rarely)43. The inventories drawn up by local magistrates listing the possessions of those who died in May or June of 1871 (probably victims of “the Bloody Week"), as well as the claims for compensation submitted by those who suffered losses due to the Siege of Paris and civil war, reflected a variety of situations. One marble worker had owned nothing but a blouse, a carpenter’s outfit and a work jacket, but a cold glazer in rue de la Folie-Méricourt claimed losses worth 420 francs for his “work clothing” (three pairs of overalls and three work shirts) as well as a frock coat in fine black wool and three pairs of trousers, including two made of fine wool, and two dress vests44.

This type of smart wardrobe would have been owned by the more well-to-do workers. Since their strike in 1845, carpenters were paid five francs a day45, a very handsome wage at the time. As for the carpenter in Le Play’s monograph, he was a gâcheur de levage or worksite foreman. The point is that these workers elected to wear their work garments only when on the job. Other workers for whom financial resources were not an issue continued to prefer wearing the blouse during off-hours. This explains why, at meetings of the editorial board of L’Atelier, a well-known working-class newspaper of the 1840s, some editors would be “wearing blouses, the others frock coats”46 and why, in a court case in 1855, bronze foundry workers accused of violating the strike ban appeared in attire “ranging from blouse to black suit, worker’s cap to felt hat.”47

For any self-respecting worker, there was a choice to be made: wear the blouse or wear a suit.

The end of the blouse

In the next part of our chronicle, we will be focusing on the disappearance of the working man’s blouse in the public space, whether for Sunday or work-a-day wear. How and why did this trend towards the social uniformization of self-presentation emerge?

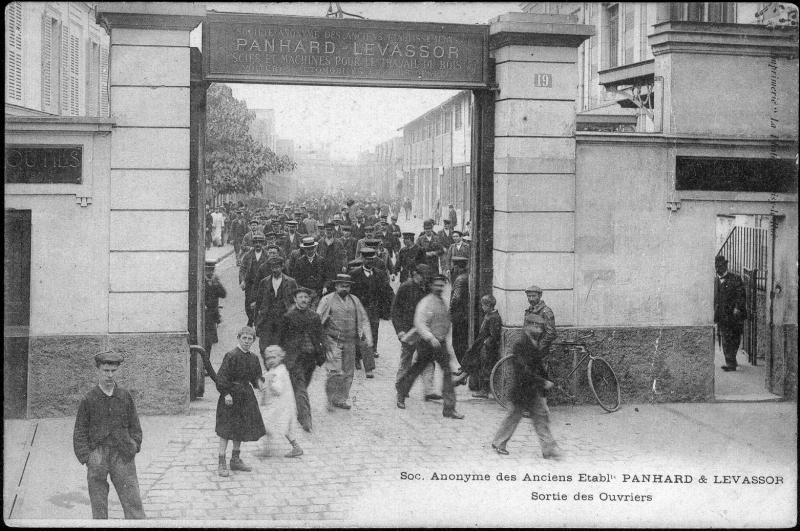

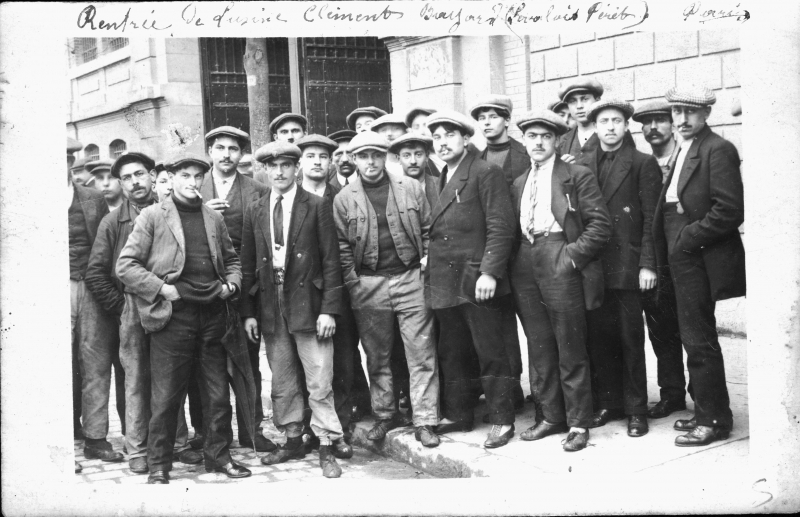

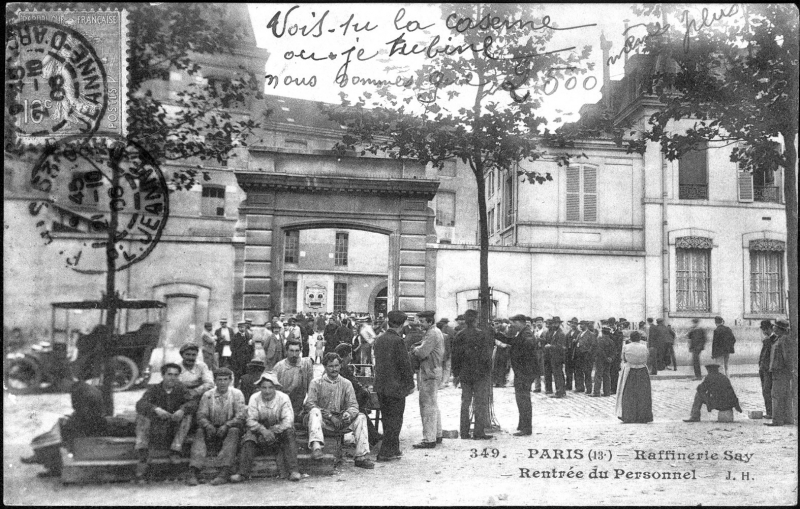

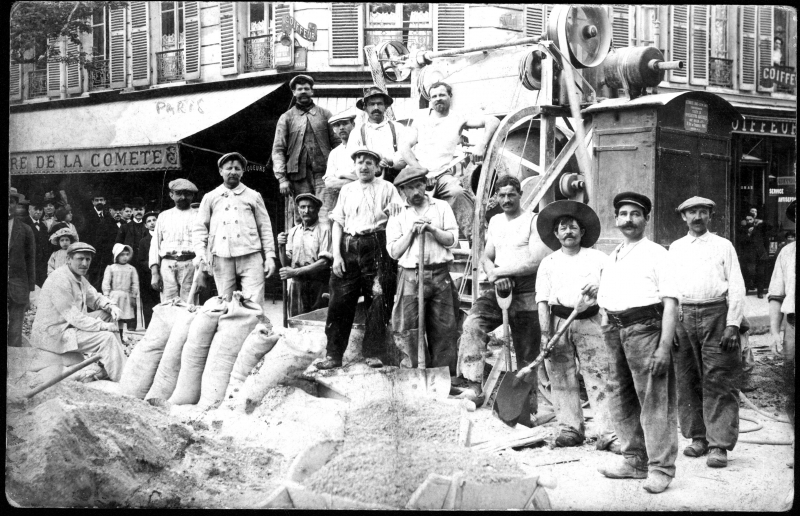

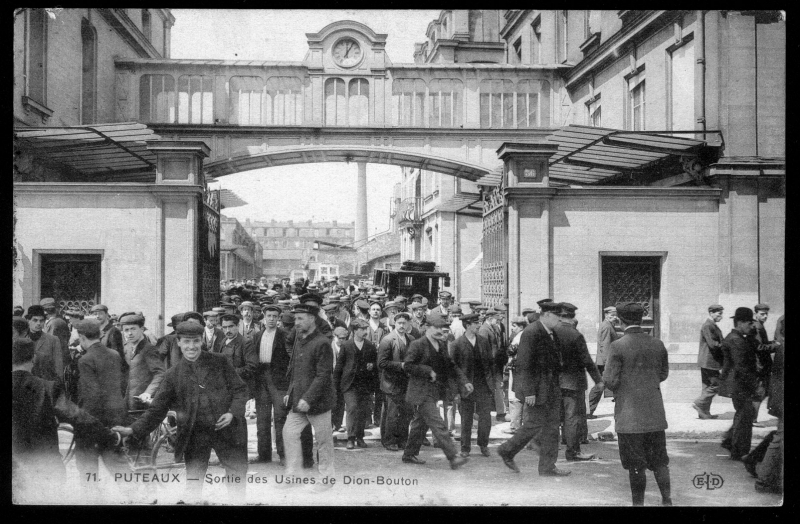

That workers stopped wearing the blouse is indisputable. At the turn of the 20th century, dozens and dozens of picture postcards of workers leaving (or entering) factories in and near Paris show that the days of the blouse were over48. While a few blouses might be spotted here and there – looking more like long aprons – the great majority of workers wore a disparate outfit of jacket, vest and trousers, more or less the worse for wear, topped by a cap. A straw Panama hat or a watch-chain emerging from a vest pocket might add a touch of elegance. What indicated the wearer’s social class, more than the garments themselves, was their poor quality and the degree of wear and tear. This trend had already struck many outside observers. In 1887, Denis Poulot deemed that workers had gained in dignity over the past twenty years. By way of proof, he remarked that, at a conscription lottery held at the city hall of the eleventh arrondissement of Paris, only “five or six, at most” of the 1,400 conscripts wore blouses.49 Another observer of the public space felt that “progress” in “worker attire” had been attested by the simple fact that, on February 17, 1905, only three out of 105 workers were wearing blouses on Place Saint-Gervais, where masons gathered in hopes of being hired50. In 1907, a policeman on duty at Place de la République on May 1 (International Workers’ Day), witnessed the arrival of many demonstrators dressed “fairly coarsely” albeit “properly”51. The “blouse-wearers” – to borrow the term used by the Préfet de Police, de Maupas – had changed their ways.

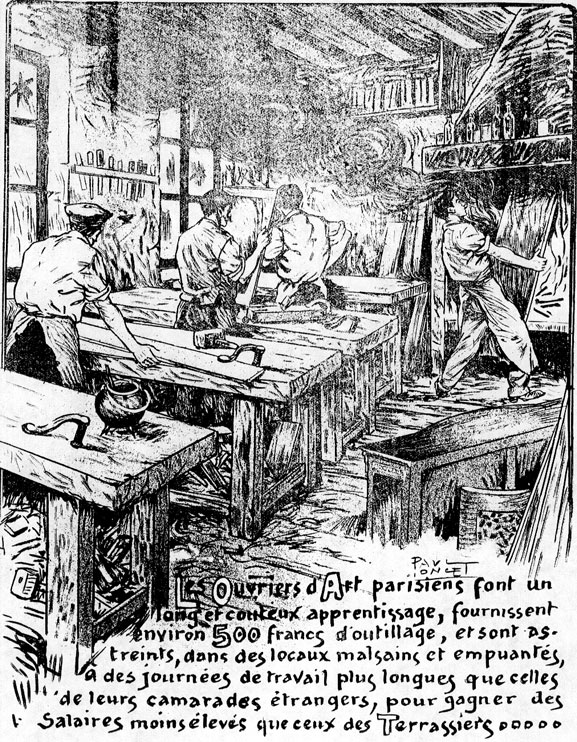

Front page of L’Ouvrier en meuble, May 1, 1912, a publication put out by the National Furnishings Federation.

Drawing by Paul Poncet.

Naturally, it became even more de rigueur for many workers to dress well on Sundays and holidays. On this score, we could cite nearly all of the monographs of the day, especially those written by Le Play’s disciple, the economist Pierre Du Maroussem52. By this time, bowler hats, top hats, cravats and patent leather shoes were being added to fine wool frock coats and suits to complete the look. Writing about their childhood before World War I, many equated fine Sundays with fine attire:

“There were also marvelous days on which we all set off for Suresnes in an excursion boat. I can still see my father in his alpaca jacket and boater hat, my mother in a white bodice with leg-of-mutton sleeves and a bell skirt.”53

The father of the woman speaking here was a house painter and her mother a factory worker.

Many authors pointed out that working-class budgets had seen an increase in spending on clothes. One went so far as to declare that “it costs more to buy clothes than to rent lodgings”.54 It is doubtful whether this claim could be made for Paris. The amount spent on clothes by a working-class couple appears to have been lower than the annual rent for a more or less decent place to live (about 400 francs circa 1900). While proletarian clothes imitated the wardrobe of real bourgeois, they could not compare in terms of quantity, quality or value. Nor should we forget the mass of those whose finances prohibited them from donning finery once a week. The family of a tanner on the Bièvre River, who had become a ragpicker due to a shortage of work, never went out on Sundays. The reason, we are told, was “a lack of money and clothes clean enough to make an honorable appearance amidst a popula tion in their Sunday best.”55 In “This Misery of Boots”, published in 1912, H. G. Wells pointed out that those without wearable shoes were cut off from the rest of the world56. Some parents used this reason – in good faith or not – to justify their child’s absences from the communal school: “The father did not have the heart to inflict this humiliation on his child before more well-to-do schoolmates”57. There was a school fund to provide shoes for the poorest pupils, but there was no “Sunday best” fund to help poor families take the excursion boat to Suresnes without shame.

The fact remains that workers were spending more on clothing, contradicting one of Engel’s “laws” of consumption whereby this expense item would remain constant in a working-class family budget58. Above all, the effect was to “standardize” the appearance of workers. For Sunday wear, the bourgeois dress code was gaining devotees. On other days of the week, workers were increasingly donning cheap ready-made garments, which is what really killed off the blouse.

The manufacture of ready-made clothing was one of the silent revolutions of the 19th century. What counted wasn’t machines, but the idea of attracting a new clientele by setting fixed, low prices and calling on the endless supply of cheap laborers working at home59. A new clientele? Vendors of secondhand clothing rapidly gave way to “merchant-manufacturers of new clothes”. At first, they specialized in cheap new garments that copied bourgeois attire. One of the pioneers in this sector, Pierre Parissot, started out in 1824 by manufacturing “work outfits” – blouses, work shirts and overalls – but very quickly switched to “full suits at low prices” so that customers could “afford to wear new clothes.” As a result, his business, La Belle Jardinière, prospered and others followed suit60. The blouse market was not sufficient in itself, but blouse-wearers seeking distinction belonged to the new clientele.

At the end of the 19th century, the vulgarization of “Sunday best” dress and the purchase of low-quality jackets and trousers for everyday wear marked a victory for the industrial garment industry. Early in the century, the “good clothes” that many workers liked to wear still probably came from traditional secondhand channels61, but there can be no doubt that, after 1860 or 1870, the merchant-manufacturer had become the clothier of choice for the poor classes, to the point where they abandoned the blouse for everyday wear. This would have to be confirmed by a detailed analysis of the quantities produced and prices62, but clearly the business of supplying garments to the working classes was booming. One factory worker named Lebrun was able to change his Sunday suit every year for 25 francs.63 An advertisement for the blue-collar co-operative store La Bellevilleoise claimed that, in the “new products” section, madeup “suits” started at 20 francs and trousers for 5.75 francs. If a co-op member wished to have garments made to measure, he would have to pay at least twice as much64. A 1907 survey on undergarments reported that wearing an undershirt, whose price had dropped from 5 francs to 1.95 francs apiece, had become commonplace among workers65. The fact that the poor could own a change of clothes and dress like everyone else was hailed by Liberal economists as the biggest benefit of the garment industry:

“Most assuredly, a manufactured garment cannot compete with a fine bespoke suit supplied by a tailor […] It replaces the rags or those almost ridiculous clothes that a great many peasants and workers were wearing twenty years ago. Today, one cannot go to an school for adults or a large gathering of workers without being struck by this happy transformation of their manner of dress, due in part to the garment manufacturing industry.”66

Furthermore, this “happy transformation” was also thought to reflect a change in attitude. According to a major garment manufacturer:

“Workers that used to be clothed in coarse, plain-woven cloth or mended rags are now able to wear a suit. This manner of dress has become familiar to him, elevates him and obliges him to respect himself.”67

The days of “Sublimism” were over.

Buying on the installment plan, which suited the working man’s budget, contributed the most to the rise and triumph of garment manufacturing in the second half of the century. Initially used experimentally and on a small scale by clever merchants, the purchase of clothes on credit68 made the fortune of specialized businesses, the most famous of which was the one started by Crespin. The customer paid a portion of the value of the desired object, went to pick it up at the store, then paid off the balance in small installments, recorded in a credit notebook69. In 1872, Crespin established a store on Boulevard Barbès that was subsequently rechristened Magasins Dufayel, whose catalogues tempted low-income families by making it easier for them to present well in terms of their personal appearance and their home. Today, it is hard to conceive of why this scheme was such a tremendous success. According to the Bonneff brothers, who were Socialist journalists, everyone was buying on credit in certain working-class buildings. In order to pay for exceptional or current expense items, an entire generation was willing to turn over, not without risks,70 a portion of its savings to the powers behind the scenes of the garment industry.

The success of stores offering installment plans was often attributed by contemporaries to their highly aggressive sales tactics. It was thought that they would do anything to land new customers.71 At the same time, customers let them get away with it. The garment business offered a solution to all those that had previously had to “make do” with wearing the blouse, to their great humiliation. For workers advocating the suit, the resulting uniformization of dress was not a disadvantage, on the contrary. In 1872, a former director of L’Atelier, a typographer named Leneveux, wrote that dress should not serve to categorize citizens and further commented that:

“No doubt, wealth will always be recognizable in a close examination of apparel, due to the fineness of the fabrics and clothing. However, regarding the overall effect of the first impression, it will injure none if, for all and sundry, the same broad principles apply to the entire outfit.”72

It suffices to read certain reports by Parisian workers-delegates to world fairs in the United States to observe how greatly they were struck with the dignified attire of the American worker:

“It must be admitted that the American worker presents better […] When the work day is over, he dons his greatcoat and hat; in the street, there is nothing to distinguish him from the richest of bankers […]. This increases the dignity of the individual worker in the eyes of all onlookers. It is therefore our most sincere hope that the regrettable tendency to dress negligently, unfortunately so widespread among the French working class, will give way to the simple but proper dress of American citizens, convinced as we are that decent attire elevates a man and conveys his intrinsic value more effectively.”73

This perspective makes it easier to understand the success of a man like Dufayel.The idea of donning “proper” attire at the end of the work day is especially noteworthy in that it implied changing clothes at the workplace. Many workers yearned to be able to wash the dirt from their hands and face and change out of their work clothes before leaving their atelier74. In 1867, the workers in charge of melting used type expressed the view that all print shops should have a changing room in which personnel could leave their clothes75. Others spoke of the need to “bathe” and “change clothes” in order to “present themselves to the world,” but did not know how they could manage “on such a low wage”76. A few establishments did possess such installations. Since the Second Empire, the big gasworks in Paris had provided a wash room where workers could wash and leave their clothes.77 In another instance, according to the workshop floor plan, an upper-floor jewelry business on rue Jean-Jacques Rousseau even featured a changing room for men, another for women and a third one, separate, for employees78. Each group had its own space.

The turning point was probably the law of 1893 on occupational hygiene and safety, which required employers to “provide their personnel with the means of ensuring individual cleanliness, changing rooms with washbasins as well as water of good quality for drinking purposes”79. One can imagine the resistance among employers, especially in the matter of providing space-consuming changing rooms. Some simply refused and others got around the law. In the cabinet-making shops of Faubourg Saint Antoine, no precautions were taken to protect workers’ belongings. One labor representative protested as follows:

“...unprotected, hanging from a nail in any corner that happens to be clear of workshop clutter, [workers’ clothes] end up soiled, worn and scorched by all these particles. That’s why, despite their good will, few workers manage to have clean clothes.”80

In 1913, the workers at a mechanized carpentry shop on avenue de Suffren denounced the hazardous nature of the machines to the labor inspection department, adding the following:

“As for hygiene, I have not mentioned it because there are no washbasins or changing rooms of any kind. We are obliged to go home in an absolutely disgusting state.”81

In many sectors of industry, the separation between work and street continued to be unknown, due to employer recalcitrance, worker timidity and/or a lack of real power on the part of the labor inspection department82. But more and more workers were demanding “the right to be clean”83. Changing into street clothes required not only a place in which to change, but also a change of clothes. And what better way to obtain an affordable change of clothes than to purchase cheap ready-made garments? The workers posing or appearing in picture postcards of factories at closing time look fairly presentable thanks to Dufayel and industrial garment industry.

Going counter to the norm

But the chronicle of this norm is much less linear than one might think. There were various forms of worker reticence or resistance, whether conscious or unconscious, and there was even a strong, albeit purely symbolic, backlash.

First of all, the industry had many dissatisfied customers and paid its workers poorly. The mason Martin Nadaud described a disappointing experience. For his first trip home in 1833, he had bought a wool suit, but it turned out to be “rubbishy”84 and the pants split the first time he wore them:

“Fortunately, I had bought a fine blouse with a blue and red collar and a tricolor belt, which was very fashionable at the time. Like the proverb says, my blouse hid everything and I could still feel proud and look fine.”85

As we might recall, the low prices of industrial garments were made possible by lowering the wages. Even hands working for good tailors were so badly paid that they had to buy inferior, machine-made goods:

“Industrial fabrics are entirely lacking in robustness. When a man who works from morning till night to make luxury clothing for others is reduced to wearing mediocre fabrics that fall to pieces, he deplores the contrast!”86

In addition, many voices rose up against buying on the installment plan. One of them was a labor representative named Auguste Keufer:

“Buying on credit is risky, for it encourages useless expenses. Workers must be made to give up their illusion – firmly entrenched – that they are getting a bargain when they buy on credit. This is not true and it’s important to keep telling them, to keep crying out that the more they pay cash, the less they will spend and the more they will safeguard their independence and peace of mind”87.

Perhaps more effective than these warnings was the vague feeling among workers that to appear dressed like a bourgeois was to betray themselves and their class. Not all of the French worker-delegates to world fairs were impressed with the fine appearance of the foreign proletarians that they encountered. In 1873 in Vienna, they reported that the Viennese workers liked to dress up:

“They don a hat – few wear a cap – and rarely go out in work clothes. Their cleanliness is proverbial and their clothing bears this out.” But they also pointed out that workplace discipline was harsh and the local workers had no trade association.88 They thought Viennese workers should tackle these issues rather than care for “frivolous externals” such as “having fine clothes or dining at brasseries patronized by high society”...89

Early in the 20th century, labor representatives leveled sharp criticism at workers, such as upholsterers or electricians, whose employers required them to dress properly before presenting themselves to customers. It was thought that these workers believed themselves to be superior, like “aristocrats of the proletariat,” because they dressed well and rubbed elbows with members of upper-class society:

“They say that clothes don’t make the man. But clothes – a work shirt versus a jacket, a bowler hat versus a worker’s cap – are all that it takes to create a ridiculous gap between two equally exploited workers, a gap that seems to create a sort of ’aristocracy of the proletariat’, to the great delight of our masters.”90

The truth was that smoking cigars, following horse racing and wearing “detachable collars with fine ties” did not prevent a worker from being paid a lower wage than an earth-moving worker with “less freedom in terms of language, appearance and even thought”91. For these purists in matters of dress, an elegant suit on a working man was very likely to conceal a spineless soul, and an obsession with external appearances led straight to egotism.

Of course, this point of view – which would have justified the arguments put forward by garment manufacturers – was contradicted by many examples. Du Maroussem spoke of a worker engaged in “high luxury” cabinet-making who was not afraid to wear his Sunday best every day, but was not at all bourgeois in outlook. A former supporter of the Paris Commune, the man was an influential member of his trade association and read the Socialist press. He liked to say that “a good revolutionary is one with a full stomach”92... and, one is tempted to add, a full wardrobe. This being said, the argument of class betrayal could not be a matter of indifference to activists. What should they do, then? Dress well, but “without excess”, like Lebrun, the worker mentioned previously who, having become an anarchist, stopped wearing a top hat and frock coat: “I was getting too bourgeois […]. My clothes were not plain enough.”93 Others, no doubt only a handful, remained true to the blouse and work shirt in public, at risk of drawing even stronger abuse than in the past. One labor representative in the printing industry, Ferdinand Castanié, left an edifying account of a visit to the national library on rue de Richelieu in 1903:

“Although the clock had already struck nine some time previously, the door to the sanctuary containing the famous books was still closed. I read a newspaper to pass the time... Finally, a guard slowly opened the door. He seemed to be squinting hard at the title of my newspaper and, as I prepared to enter, blocked my way.

“Have you read the new regulations?”

I mildly pointed out to this obliging civil servant that I had come to the library to read something else entirely and had no time to waste. During this brief exchange, he had stepped aside several times to let several people pass, without making any observations.

“Well then,” he said, insolently. “Read them!”

I was forced to give my full attention to the famous regulations, which were not at all new and stated that “all readers must provide proof of their identity and place of residence.”

“Very well, “ I said. “I have everything you require.” In a hurry to get the business over with, I showed him my papers.

“Those are no good,” he said, disdainfully. […]

Then, walking towards me and eyeing me with an air of supreme disgust, he suddenly pushed me outside, saying:

“Nobody goes in wearing a work shirt and blue trousers!” And he muttered vague insults.”94

Finally, just before World War I, the popularity of certain “non-standard” types of dress sprang from a symbolic resistance to uniformity. In the construction industry, some workers remained loyal to their former modes of dress, both for work and everyday life. While house painters had stopped wearing the blouse during off-hours, carpenters had retained their corduroy jacket, baggy trousers and red or blue flannel belt. The outfit worn by earth-moving workers was very similar: corduroy pants, red belt, overalls and felt hat. They all had their regular suppliers for both tools and clothing:

“On work days, carpenters dress like carpenters […]. They buy their work clothes at specialized stores, the two largest of which are on rue du Faubourg Saint-Martin, facing each other. One of them had a sign bearing Saint Joseph on it, which is definitely in keeping with local color. This store is reputed to supply clothes to the bulk of workers in that profession.”95

Similarly, a single dealer in Paris supplied earth-moving workers, familiarly referred to as “members of the guild for moles”96.

The members of these professions wore distinctive outfits and had their own suppliers. They weren’t afraid to stand out in public, even when they were off the job. Robert Debré, the prominent pediatrician, recalled seeing certain workers when he was attending the Université Populaire in the 15th arrondissement of Paris: “In particular, I remember a carpenter, a big, sturdy fellow who was always wearing a wide belt of red flannel wrapped several times around his waist and a pair of slightly baggy, brown corduroy pants.”97

One account of childhood memories described an old earth-moving worker who lived on rue Clission in the 13th arrondissement. He lived quietly and liked to take a Sunday walk around the neighborhood. What did he wear?

“On Sundays, he would put on a clean shirt, his least soiled felt hat and his least grimy overcoat, trading his dirty old pants for a pair of brand new, black corduroy trousers, and his red flannel belt for a blue one. With one hand behind his back, he would set off, always at the same slow pace, to stroll through the streets.”98

For him, Sunday was a day set aside for cleanliness. “Earth-movers today are really concerned about their physical appearance,” noted a labor representative in 191499. Perhaps so, but this did not necessarily mean that they had to own two types of clothing.

The construction worker’s outfit enjoyed substantial prestige in the early 20th century. It figured prominently in drawings and posters, a key element of period socialist and labor imagery. “The people” – organized, engaged in the class struggle – were always depicted wearing the outfit of the carpenter or earth-mover. Corduroy pants and wool belts studded the pages of the socialist newspaper L’Humanité and La Bataille syndicaliste, the daily put out by the Confédération générale du travail (CGT). Like the blouse in 1848, baggy work trousers had become emblematic of the proletariat. It came as no surprise when, at festive gatherings organized by activists, the singer Montéhus appeared “dressed in blue corduroy pants and a red shirt”100. It would be interesting to delve deeper into this trend, very striking but out of proportion with the space in the social landscape actually occupied by these suit-less workers.

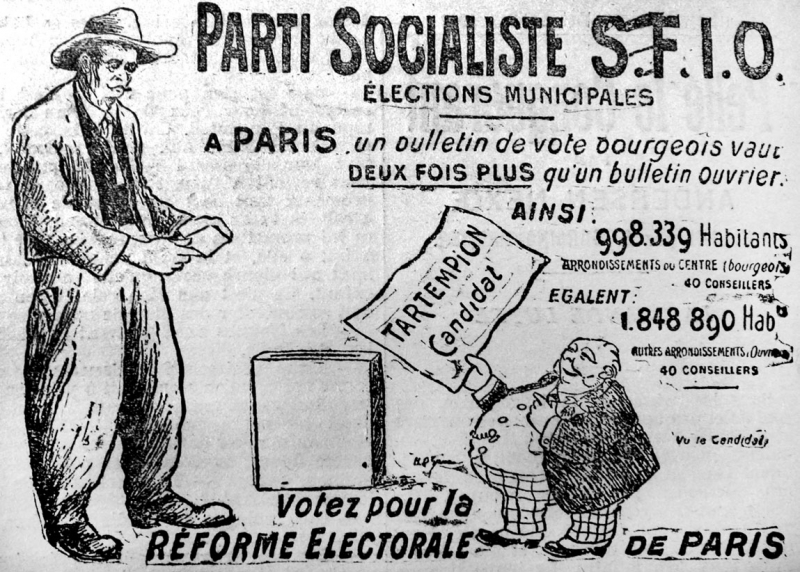

Election campaign poster, 1912 Reproduced in the May 3, 1912 issue of the Socialist newspaper L’Humanité.

The poster denounced the unfairness of Paris municipal elections: each district was entitled to a seat on the city council, irrespective of population. One notes, however, that the portly bourgeois in the poster cannot compete sizewise with the carpenter in his carpenter's pants... Similarly inspired drawings appeared in the February 21, 1914 issue of L’Humanité as well as the May 9 and 17, 1911 issues of La Bataille syndicaliste and trade union propaganda leaflets.

L’Humanité, May 3 1912.

Why did this mode of dress enjoy such prestige? At the time, construction workers were spearheading the Parisian labor movement. The earth-moving workers had led major strikes, often successful, during the construction of the Paris metro101. In 1907, the carpenters had obtained wages of 1 franc per hour, double what was paid in 1845. Their unions were rich and powerful. One CGT leader, Georges Yvetot, declared that the earth-movers “were the brave aristocracy of labor”102, which was, addressed to heavy manual laborers, a fine compliment. But there was something else behind the return of this vestimentary particularism: the need for a convenient social representation that could be understood by all and inspire the working class. It had to be out of the ordinary: a victorious striker could not appear in a suit.

Here, we have confirmation that the story of the working man’s appearance was not about dispossession, loss or social leveling. As we have seen, it was consistently marked with the stamp of pride and dignity, which explains the popularity of the blouse or the suit, depending on the period and the individuals involved. The norm was shaped by the aspirations and values of the working class.

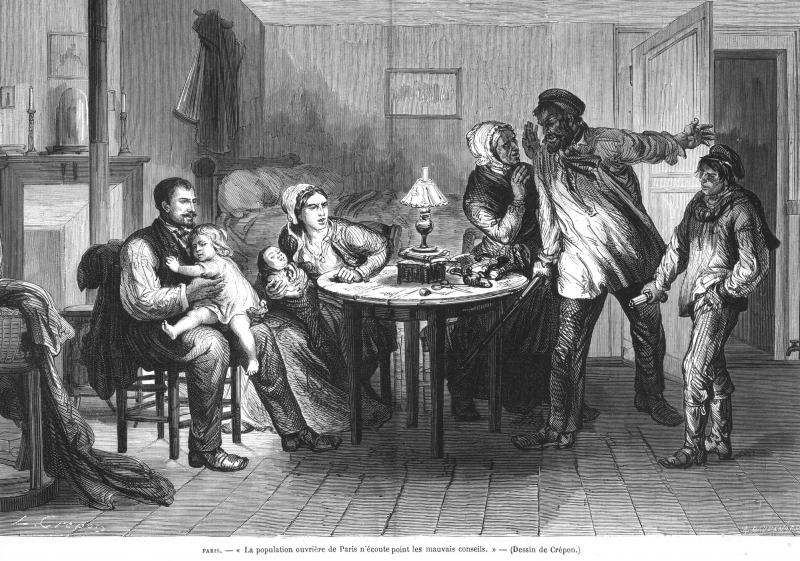

“The working population pays no attention to bad advice.”

On February 7, 1870, shortly after the funeral of journalist Victor Noir, Henri Rochefort, MP, was arrested at the Salle de la Marseillaise meeting room at the La Villette, rue de Flandre. This triggered three days of rioting in Paris, with the beginnings of barricades. There were many arrests and convictions for seditious speech or unlawful gatherings. The demonstrators – workers without official leaders – had called upon the population of the faubourgs (working-class neighborhoods) to follow their lead in hopes of inflaming public opinion in Paris and bringing down the Empire. The scene shown here is supposed to represent an attempt at recruitment. A rioter in a blouse, accompanied by a young clone, is exhorting a peaceable worker to take to the streets and fight the Empire. Clearly, he’s wasting his time. The illustration is a bit tricky to interpret. One might be tempted to see a “blouse versus suit” contrast between the intruders' clothes and those of the man of the house, assuming that the garment hanging over the back of the chair is an overcoat or frock coat and not a blouse. In other words, the blouse would suggest rioting, the suit law and order. A worker dressed properly is a right-thinking worker. Actually, this illustration refers to something else occurring at the time. During the riots of May-June 1869, February 1870 and also in June 1870, when Parisians once again took to the streets, the moderate Republican opposition party declared repeatedly that all of these disturbances were caused by policemen in disguise, the “white blouses”. The garments were white either to make the provocateurs look like construction workers or because, never having been worn, they were too clean to be real. The memory of the “white blouses” of the Empire period remained vivid: they were still being mentioned around 1900, proof that many believed the accusation to be true. Readers of Le Monde illustré would inevitably think that sketches of individuals hanging around barricades represented police agents. The newspaper did not say actually so and even quoted from Amédée Achard's virulent article in the very official Le Moniteur universel calling demonstrators good-for-nothings and cowards. Nevertheless, a degree of ambiguity remains. At any rate, the blouse – white or not – did not get good press. See the clemency petitions for some of the rioters of February 1870 (Archives nationales, BB 24 722) and A. Dalotel, A. Faure, J.-C. Freiermuth, Aux origines de la Commune: le mouvement des réunions publiques à Paris, 1868-1870, Paris, F. Maspero, 1980, pp. 348-354.

Engraving published in the February 19, 1870 issue of Le Monde illustré, pp. 209-210.

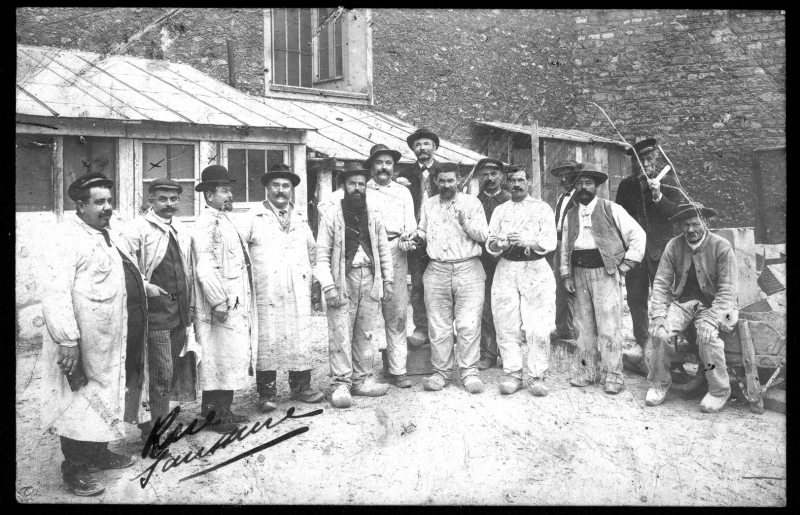

Real-photo postcard sent in 1906. It shows workers at a construction site on rue de Saussure in Paris (17th arrondissement).

Collection AF

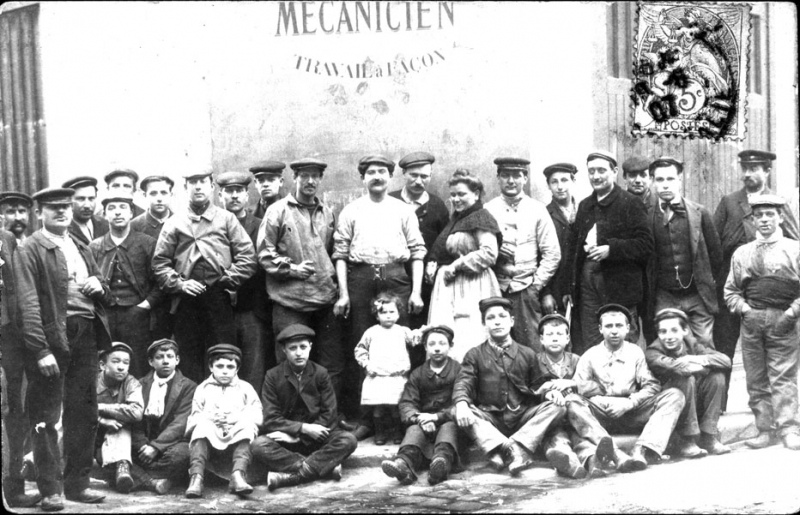

Real-photo postcard, sent in 1907, showing a group of workers, and perhaps neighbors, in front of a mechanic's workshop in Paris. The man smoking (on the reader's far right) could very well be a construction worker paying a friendly visit.

Collection AF

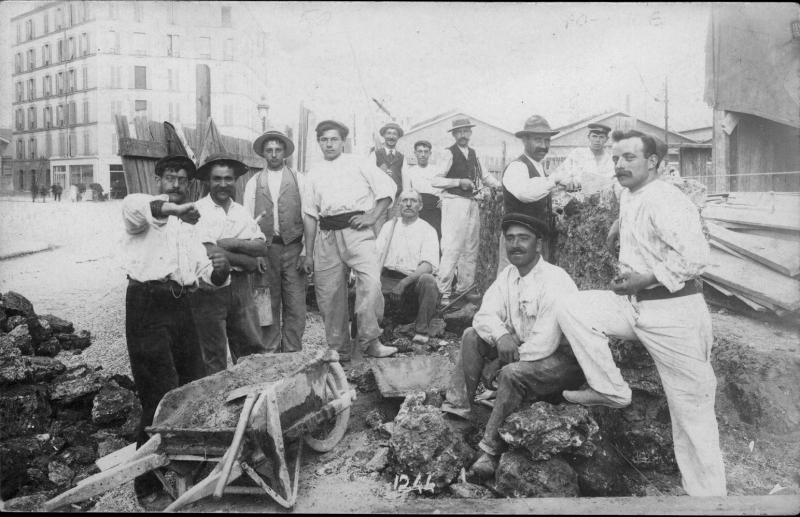

Undated real-photo postcard of workers at an earth-moving worksite in Paris, possibly in the 17th arrondissement.

Collection AF

Undated postcard of workers getting off work at the Panhard Levassor automobile factory on avenue d'Ivry in Paris (13th arrondissement).

Collection AF

Real-photo postcard of a group of workers arriving for work at the Clément Bayard factory, a big automobile plant in Levallois-Perret near Paris. The card is dated March 15, 1906.

Collection AF

This postcard says “Personnel arriving for work at the Say sugar refinery”, but more likely shows workers in work clothes on their lunch break in front of the refinery on Boulevard de la Gare in Paris (13t arrondissement). The card is dated October 19, 1906, the day of the sender’s 27th birthday

Collection AF

Undated real-photo postcard of workers at a public works site on avenue de La Bourdonnais in Paris (7th arrondissement).

Collection AF

Undated real-photo postcard of personnel from the APRA jewelry atelier in the 3rd arrondissement of Paris, posing in front of the entrance to the building. The person in the middle is very probably a young apprentice.

Collection AF

Detail of workers getting off work at the De Dion Bouton automobile factory in Puteaux, near Paris. The postmark is from 1911.

Collection AF

A crowd of workers from the Compagnie des Lampes in Ivry, near Paris, posing after work. The postcard bears a handwritten date: March 15, 1907.

Collection AF

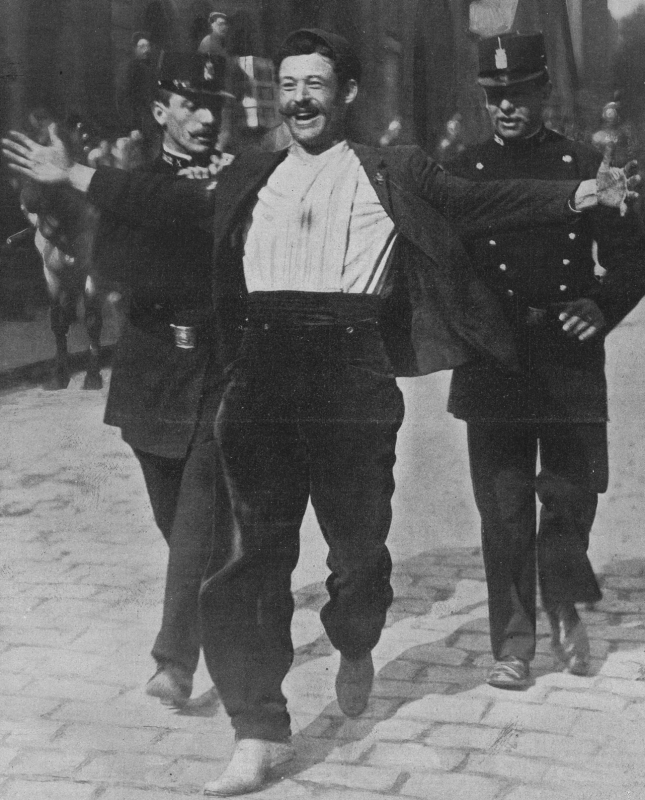

« Le bon gréviste »

This photograph, sometimes reproduced in works by militant activists, was published in L’Illustration of May 29, 1909 with the caption Le bon gréviste (“The jovial striker”). According to the newspaper, the photo was taken as construction workers left a union meeting held in a large meeting room at Le Tivoli Vauxhall, rue de la Douane. There’s nothing improbable about this arrest: 1908 and 1909 were years of rolling strikes at public work sites in Paris, especially during the construction of the metro, resulting in clashes with members of “yellow” unions and the police. Why does this earth-mover, dressed in good clothes, look so jubilant? His arms, open wide, seem to be pushing back the policemen clutching his jacket. Is he rejoicing at the prospect of victory or simply happy to be alive?

L’Illustration, May 29, 1909 (p. 377)

Bibliography, museum and movies

This article would like to create the desire to see or see again at the Louver Museum La Liberté guidant le peuple of Eugène Delacroix – for us, the first representation of the worker’s blouse –, and to read and read again the work of Jules Vallès who wore formal dress but wrote on blouse in several places (See La Pléiade/Gallimard or Éditeurs Français Réunis).

Two movies recreate, as much as possible with cinema, the popular blouse of the 19th century. Moi, Pierre Rivière, ayant égorgé ma mère, ma sœur et mon frère… directed by René Allio (1976) and made from the story of the Norman parricide, show the peasant blouse; La Commune (Paris, 1871), made by Peter Watkins (2000), showed the worker’s blouse with an amazing precision.