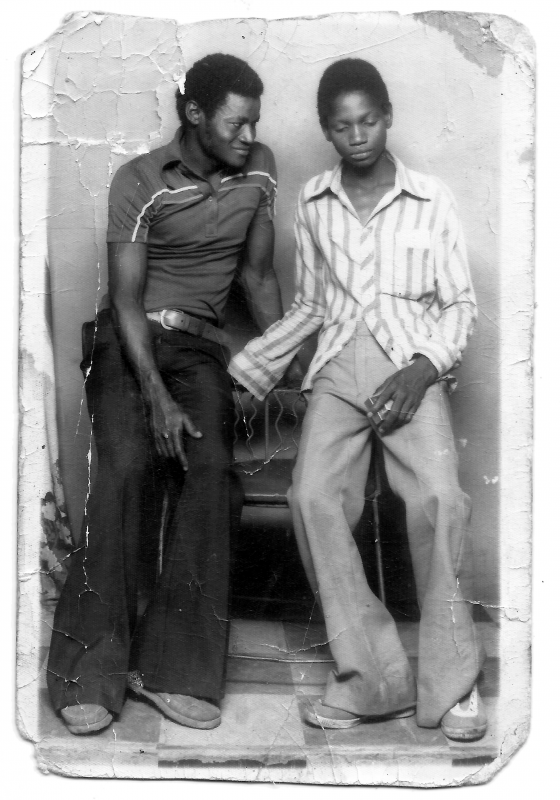

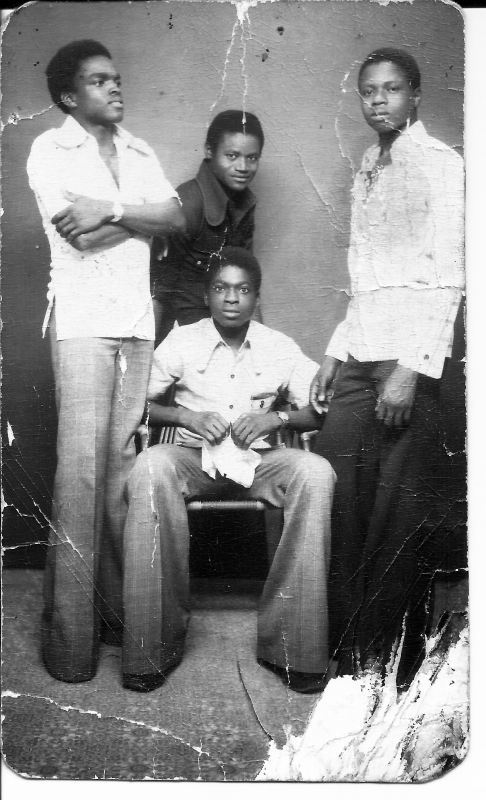

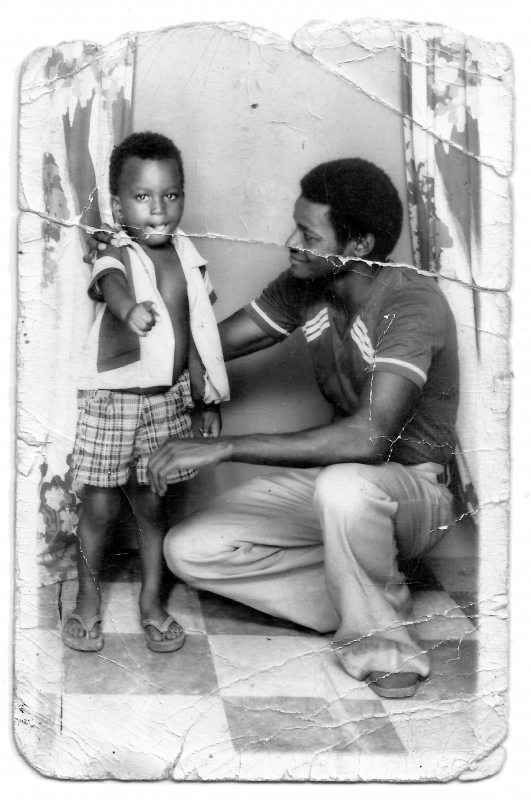

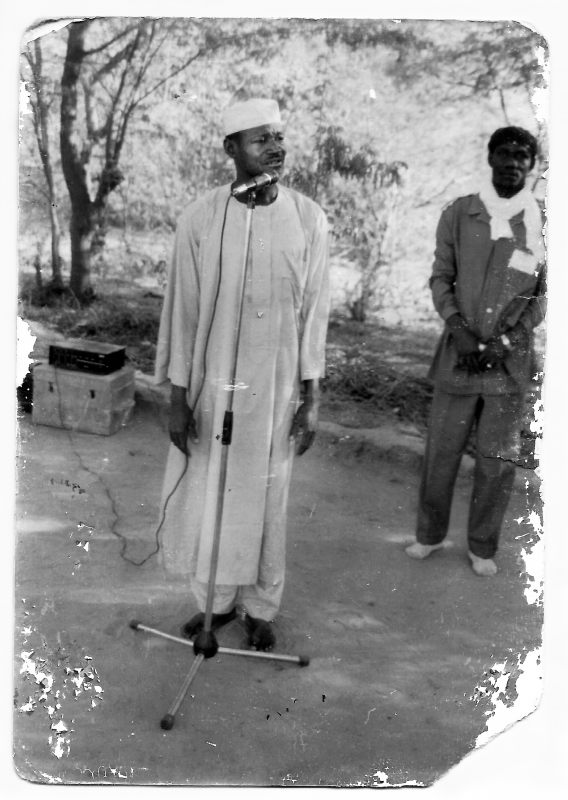

The pictures that illustrate this account were collected by Tarno's friends. This one along with the two others were taken in a photography studio in Tahoua, Nigeria, at the end of the 1970s.

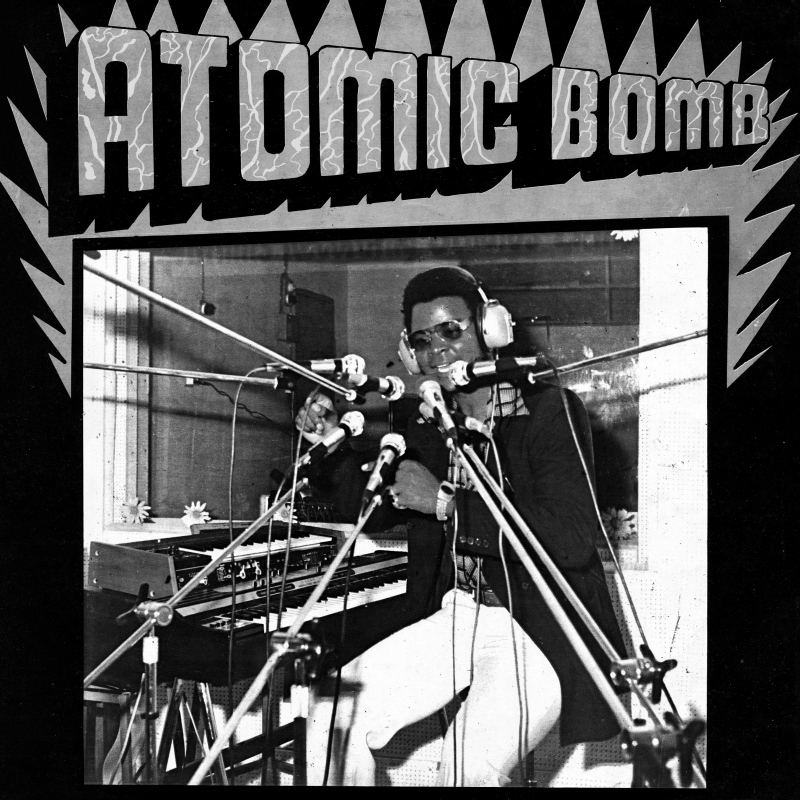

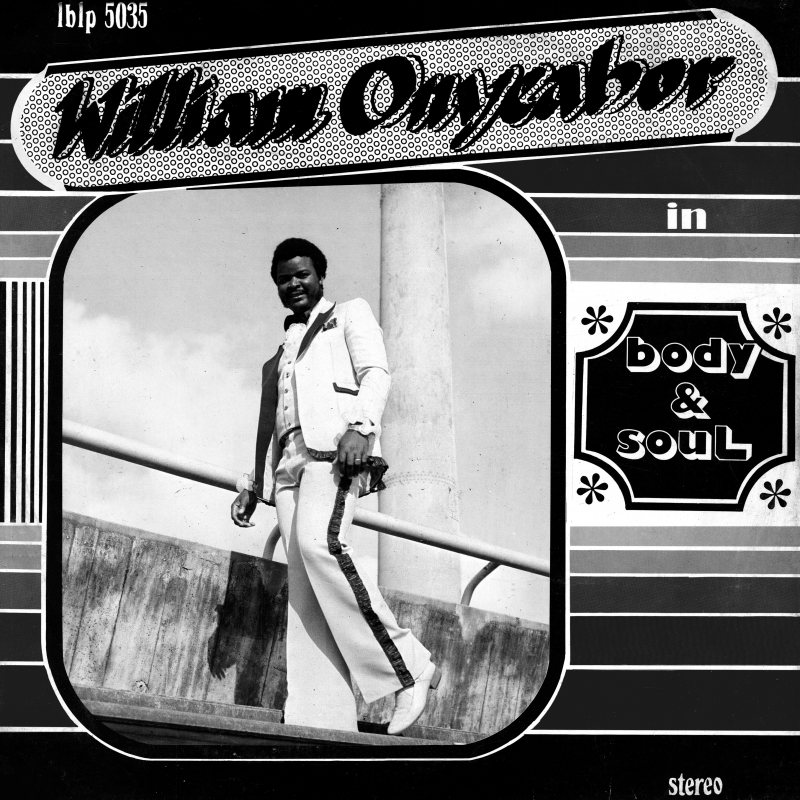

The first memories of Tarno, a nickname we called Mohamed, and who would today be a little over 60, come back to me from 1978-1982, my elementary school years. Mohamed Tarno was born in Keita, my village in the department of Tahoua in Niger. He would, as did much of the youth of my village, migrate back and forth from Nigeria, and he was settled in the town we call Jos1. He had the peculiarity of being passionate about fashion. He didn’t just shop for clothes: he wore the most beautiful, the most sophisticated clothing. I must say that at the time, my classmates and I alike, did not know what fashion was, we were not capable of grasping this abstraction and name these clothes as being “fashion”. But we could see that his clothes were different, adjusted, and that they looked like those worn by singers and movie stars that we could spot in magazines or on posters. He particularly liked jeans, and we were fascinated by his most variable pieces, each prettier than the other, of which he had an incredible collection. We would call him today – and as soon as the 1970s in Congo – a dandy, but at the time, in Keita, in our language [Houssa], we had the term “gaye” that can be translated as “he who dresses up”. He himself would say that his profession – besides his day “job” – was to be a “gaye”. There was a small congregation of “gaye” in the region, but he was the only one in Keita. He had the habit each time he was back from emigration – when we would set up the norias – in the summer and sometimes he stayed until September, October, before going back to Jos, of staging his outfits in what was not unlike small shows. Every night we were treated to somewhat of a catwalk on the one and only artery that crosses the village and leads to the train station. He wore a different pair of jeans every day and always carried various accessories, particularly vinyls. I especially remember the William Onyeabor discs and his album Atomic bomb [1978]2. These vinyls were very expensive. The covers always showed sophisticated poses of characters in jackets, bell-bottom jeans as we called them, or incredible hats. Tarno looked a lot like these singers who to us were “Americans”, blacks from the other shore. We did not understand what these bands were all singing about, but they sounded modern to us. Tarno crossed the village with these vinyls in hand. He never walked around with dropped arms, gesture was very important and therefore all accessories counted. He also had very well kept shoes, in particular shoes we strangely called “Negro heads”, very beautiful black leather high-tops. They made the difference in the village. To us elementary students, he was a first class personality that belonged to another world, that of the few magazines we managed to find. He gave another value to clothing, he stood for the fact that clothing could grant another status, beyond the village’s codes. By his presence, he greatly influenced us. Mohamed Tarno was always joyful, gay, took his time before getting married, there was no doubt he had other lives. He was at once very simple and very dandy, always well dressed, always very clean. When one works, he would say, and one is sane, fashion is part of body and soul hygiene. I think we knew what he meant. The only man of his generation in whose home I saw a series of creams, of perfumes... He used to say that beautiful clothing was never to be worn on a neglected body. Tarno was a determining figure to us elementary students.

Nous Deux, Amitabh Bachchan and Tarno’s albums

Along with his attributed studio photographer in Nigeria, he tried to reproduce fashion magazine poses. He would have his picture taken for each new outfit and thus had thousands of photographs of himself, mounted in albums. Very beautiful and very joyful albums to our eyes, as to those of our elders who knew him in the 1970s. His albums brought back by photography the “truths” about emigration and the “truths” about fashion in the village. He brought to light a dream life in Jos – It must be said that the village was calm and ecumenical. When he was back in the village, it was always along with his albums and photographs. If he trusted you, you could consult them, at his house. I went there often. I would offer to go get water at the pump and in exchange he let me look through his albums. I would feast my eyes on the cuts of his clothing, the accessories, his poses taken in the studios, with a telephone or a flower pot in hand, in front of flowery or urban painted landscapes, sometimes on a giant motorcycle, an Indian Roadmaster. He would always invent an element of specific detail and each scene was put together like a scene of life. He would gladly pose with his successive conquests.

He not only imitated vinyl covers but also Indian movies – he admired Amitabh Bachchan. He was a melomaniac, he used to sing sequences from Indian musicals to us, in Hindi. We did not understand anything he articulated, but we adored the melodies, the gestures, and the expressions. He covered the song “Mile Jo Kadi Kadi”3 for example. He didn’t manage to seduce the young girls with these romantico-Indian songs, but he sure seduced the elementary school children. We were intimately convinced that he was our cultural horizon. Our dream was to be able to dress and act like him. To us, he came from the future... In the village, there was neither library nor bookstore. Nevertheless, I remember the excitement of discovering reading and the difficulty of finding something to read. I would go rummage through the garbage of the rare expatriates or I would go to the west of the village where the wind brought in pieces of magazines and newspapers. This is how I remember reading Nous Deux, Paris-Match, women’s magazines... We would devour these little bits of text and images. We would reinvent the meaning around these snippets. We caught a glimpse of fashion in women’s magazines such as Marie-Claire. I remember both photographs and text, notably on sentimental issues, answers to their readers’ questions... I didn’t always understand the meaning of the stories and suggestions, but I thought it was all very well written. To me these magazines evoked a world where people seemed to have a lot of problems. We would also observe fashion on the expatriates, or, so to speak, on the urbanites and whites passing through. As elementary school children, we scrutinized any stranger that would arrive in the village, we pored over him to see how he walked, how he pronounced words, how he dressed, what were the colors of his clothes, the patterns...At the time, we had very little contact with the rest of the world.

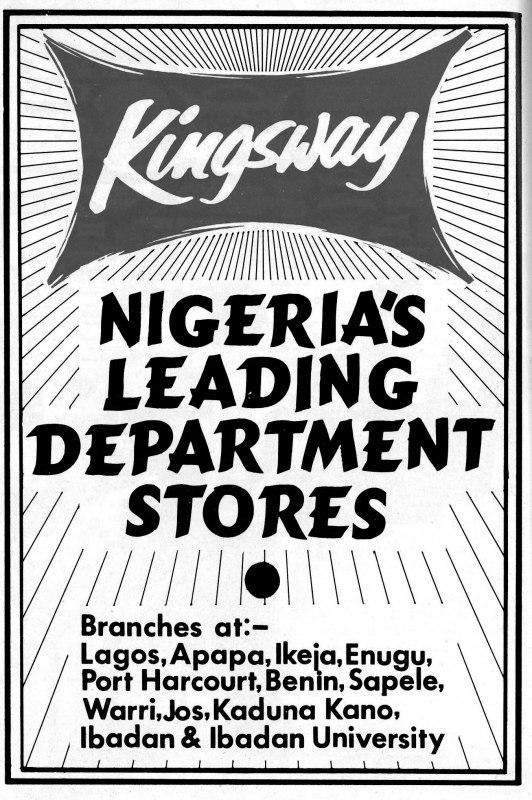

Kingsway department store commercial, one of which was active in Kano, Nigiria, the city Tarno emigrated to, 1970s

Private collection

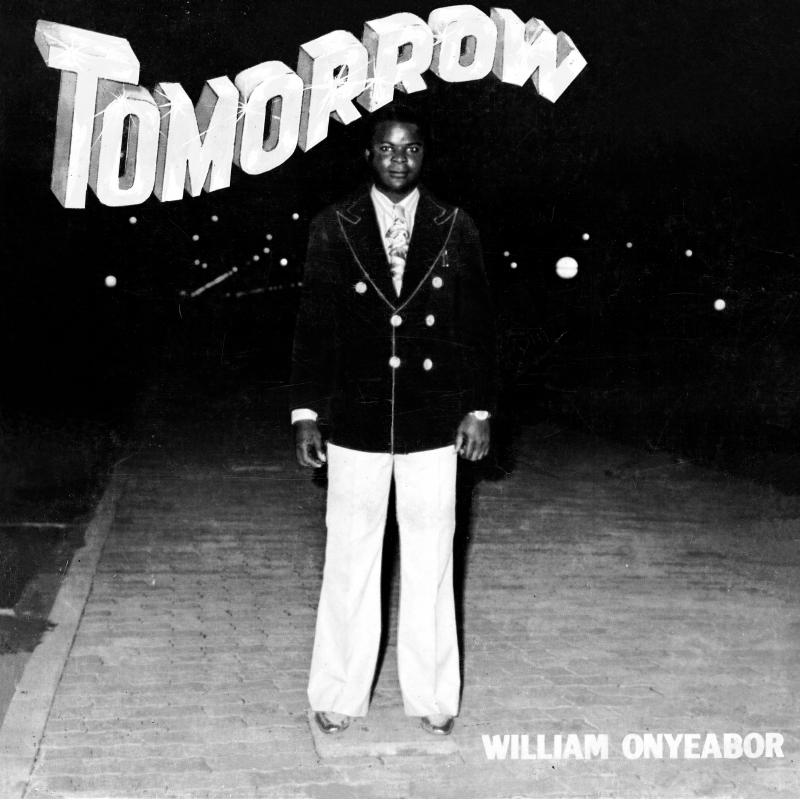

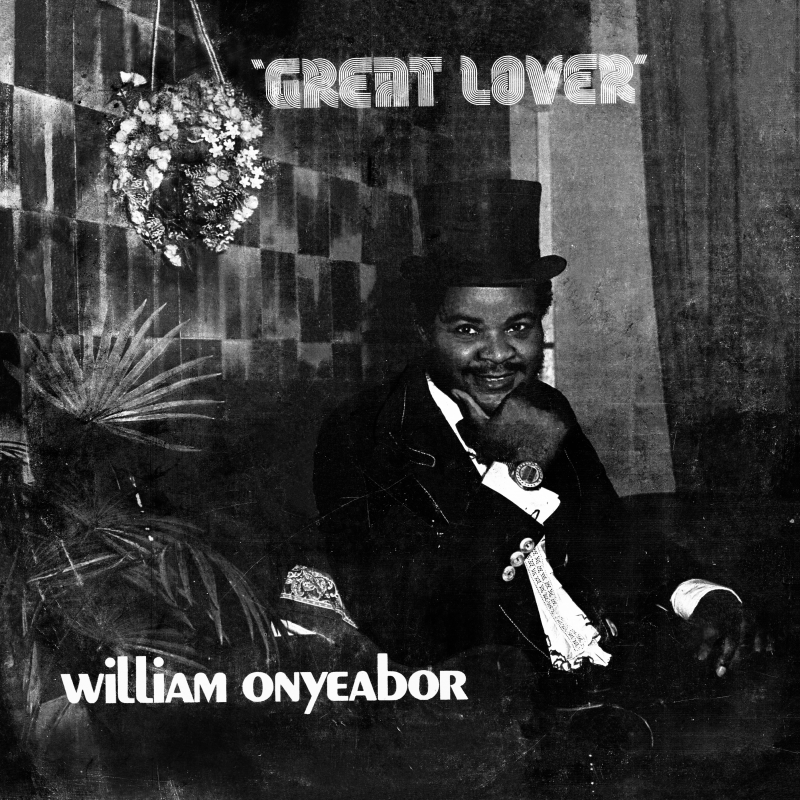

William Onyeabor's LP cover, a Nigerian musician who was active in the 1970s, let out eight funk albums from 1977 to 1985, then left show business.

William Onyeabor's LP cover, a Nigerian musician who was active in the 1970s, let out eight funk albums from 1977 to 1985, then left show business.

William Onyeabor's LP cover, a Nigerian musician who was active in the 1970s, let out eight funk albums from 1977 to 1985, then left show business.

William Onyeabor's LP cover, a Nigerian musician who was active in the 1970s, let out eight funk albums from 1977 to 1985, then left show business.

At the village

In general, we carefully scrutinized fashion, even in the village. I remember how we tried to see if we could decode the teachers’ clothing and that we had deduced that when she wore her key patterned clothing, she was mad, and when she wore white, everything was better... We had an empirical lecture of symbols and expressions notably gestural... Upon Tarno’s arrival, we became his spectators. In our village, our parents all had what you call here “African boubous”, and djellabas. It was a world of ampleness where clothing was not meant to embrace the body’s shape. Tarno opposed this: his clothing was not only occidental but had particular cuts, his jean vests had tall collars and were waisted, sometimes sleeveless to bring his athletic muscles to sight, and his bell-bottom pants were always skin-tight. Our generation, the elementary students, dressed occidental, in shirts and pants, we were already closer to Tarno than to our parents. He basically dressed like us, but at the same time, so differently: we were in the ordinary, he was in the extraordinary. For the most part our shirts and pants came from the market’s thrift shop arrivals – I don’t believe I ever bought anything else, tailored clothing, even from small-time tailors, was more expensive. Without a doubt Tarno ordered for his part his clothes from tailors because they were often very well adjusted. He also told us of the stores in Nigeria, particularly the Kingsway4 department stores.

Tarno was not unlike an extraterrestrial to the village. He had the audacity to parade, to run a fashion show every day. He was a renegade. He was almost a prophet who believed that fashionable expression must be brought to the villagers who mustn’t stay in the dark. And indeed, he opened our eyes upon another way of dress. The rest of the village saw him as a kind irreverent, maybe even a madman, because he dared to parade in front of hundreds of hilarious villagers. But he worked, brought in money, so the village didn’t have much to say. One mustn’t forget that at the time the youth was trying – even more so since independence – to be “gaye” and that in our traditional culture, it can be said that transparency was somewhat expected: if you are rich, your clothes must show it, you can’t dress in rags, you must be coherent. When the elementary school children saw Tarno, they saw fashion and modernity; when the parents saw him, they saw a young man who had successfully migrated. We said that he had “traveled”, that is, that he had seen other lands and that he had learned, he was respected for this.

Conversion by fire

Around 1982, Tarno faced some sort of an identity crisis, some said he was crazy. It was believed that he had fled Nigeria and that he had come back a bit sick. It was said that he had fits; he said that he had had a revelation and went around building little stone mosques all over the village and its surroundings. This is how he came back to us and how he finished his migration. For at least five years, he was in this agitated state. He was picked up afterwards by the emerging re-Islamisation movement, around the 1990s, that had consecrated its self to impulse preaching in the most secluded villages. Since Tarno knew neither how to read nor write Arabic, he based himself only on his own experience, notably migratory, to propose forms of abstractions that spoke to the villagers. He was articulate, he knew how to address a public. He became a preacher figure, listened to in a village where Islamic culture at the time was weak. He managed to use his capital as a “gaye” to invest himself as a preacher in the village and the countryside around it that were considered by Islam to be “savage lands” so to speak. The new religious actors, essentially urbanites, were not yet present in the countryside. Here was no longer the gentleman that we had known. He changed his clothing, his outfits, his entire fashion identity. He wore a djellaba or long boubou, like our parents in some sorts. He destroyed his clothes and burned all of his photographs. This can be interpreted as a burial of his identity. It was an identity aggiornamento by fire, by destroying his work. He wanted the village to know that he was a new man, a pious man, and a pious man does not wear jeans. By destroying the proof, he believed that no one could ever contest his new status. One day, at his place, I asked him where his photographs were. He proudly answered that he had burned everything. I was young, but I tried to convince him that he should not burn them all, that God alone is judge, that even as a dandy he loved him, that he had to keep his pictures for preaching as proof of what he had lived through and his change. How will people believe that you were a John Travolta, in jeans, on a Roadmaster motorcycle? How will you convince? In response, he pulled out discretely three or four photographs of him as a “gaye”. He was still proud to show these photographs of back when he was young. Re-Isamisation, let us not forget, was a movement of return to... a new identity. And this novelty passed and still passes through renewal of visible forms, particularly outfits. In the beginning, the new Muslims reused our parents’ clothes but for many, re-Islamisation passed through occidentalized elites that needed to find comfortable forms. Furthermore, to seduce the youth, the actors of re-Isamisation accepted the elements of the European wardrobe. The only constraint was that the body be covered; a couple additional centimeters sufficed... The colors were very sober, monochrome. By the end of the 1980s and at the beginning of the 1990s monochrome and ampleness were once again the norm amongst the population. The elites proceeded for their part to produce an identity concoction, notably passing from the long boubou to a three piece costume, depending on moments and situations. To Tarno the change was necessarily radical: abandoning his jeans, he took up the white djellaba, with a white cap as sole accessory, according to the Prophet’s tradition. A sort of total abstraction. He had his djellabas made in the village all the more so since China in those years had entered the economy of religion, and we were submerged in clothing and accessories that were imported from Saudi-Arabia but made in China. Tarno therefore bought very few and only modest, ordinary things, because he wanted to be a rural preacher, close to the villagers. This made him respectable, even if his Islamic culture was very weak. Despite this, he never condemned the “gaye”... He often asked me in the years 1990-2000 to film his preachings, sometimes very long, in hopes of spreading the word on the web. But it could be felt that he was less at ease than as a “gaye”... The fight with his identity was clear.

Until the beginning of the 1980s as a “gaye” he did not want to marry, then as a preacher, he judged that marriage might divert him from his mission. Yet with age, he married and had a daughter. A couple of years ago, my brother, that had stayed in the village, called me to announce his death. I would go see him regularly until the end and each time, since it was my turn to be the emigrant, he asked me if I would contribute to fix his financial problems. He knew we had been his “partisans”, that he had influenced us and that we could not refuse. He opened the world up to us: he was television when there was no television, radio when there was no radio, song when there was no stereo, art when there was no art, fashion when there was no fashion.