The recent visibility of Islamic culture in France may lead us to forget the customary “veils” that French women have traditionally worn: scarves, bandanas, coiffes, hats, and loosely draped fabrics worn at religious ceremonies and on formal occasions. At communions, weddings and funerals, women have worn accessories that leave the face partially uncovered but which conceal the hair and neck1.

Everyone knows that France, originally subjected to monarchs of divine right, was hardly concerned with spreading equality and liberty of the “second sex” once the state became a republic. Until recently, women have worn head coverings symbolizing their submission in a patriarchal and essentially Christian system, one that made the image of a woman with her hair down an offensive image and one of shameful immodesty. The visual significance of this remained essentially consistent during the turbulent and revolutionary years between 1780-1820 (I extend the usual period because the fashion trends have a specific chronology2), a time that witnessed not only changes in outward appearances but also profound changes in political, economic and socio-cultural ideas.

Some of the major transformations that occurred in France during the French Revolution and the early years of the 19th century included a strictly masculine democratization of public life, a deepening desire to be rid of Christianity as a religious and political system, a deepening suspicion of traditional elites, the emergence of newly powerful groups, not to mention the usual exigencies imposed by a civil war. For French women, these occurencies would lead to uses of the veil that were, at the same time, a conventional sign of one’s gender and what might be called an adaptation, at once modest and polymorphous, of fashions for the upper body in times of drastic change.

I’d like, on the basis of written and visual evidence, to concentrate on three exemplary cases of the transformations I have in mind: the elimination of modes of dress compelled by law or public opinion; the survival of some proletarian modes for a purpose of camouflage; and their eventual reemergence as elements meant to charm or seduce. My hope is that a historical perspective might do something to show that contemporary debates about what is and is not forbidden – whether or not they concern religious belief –, and about styles that imagine themselves to be outside all systems of fashions, are also about the emancipation of women (and men) inside the Christian religio-political culture. The veil has a history, particularly in periods of social stress.

Funerary Veils. Mourning and Religion

Demonstrative of the psychological and physiological transformations that took place during the French Revolution, the disappearance of the monastic and funerary veil is a forgotten phenomenon of this period. And yet, it is a legacy of the physical and symbolic unveilings demanded by the Enlightenment rationalism and recently deciphered by historians, including objections to the wealth of religious communities with fewer and fewer members; the battle against forced vocations and the “sequestration” of women deemed “idle”, “superstitious” and “barren”; the promotion of orders supposed to be “useful”, because actively apostolic orders (teachers and / or nurses, as opposed to “contemplatives”); calming of fears concerning one’s “last rest” and Salvation; distrust of funeral directors suspected of overcharging; etc.3

The figure of Truth unveiled that triumphed on the frontispiece of the Encyclopedia by Diderot and Alembert prepared the way for the images of terrified nuns – sometimes grotesque, sometimes melodramatic, sometimes serving libertine purposses – featured on works that multiplied during the last third of the eighteenth century.

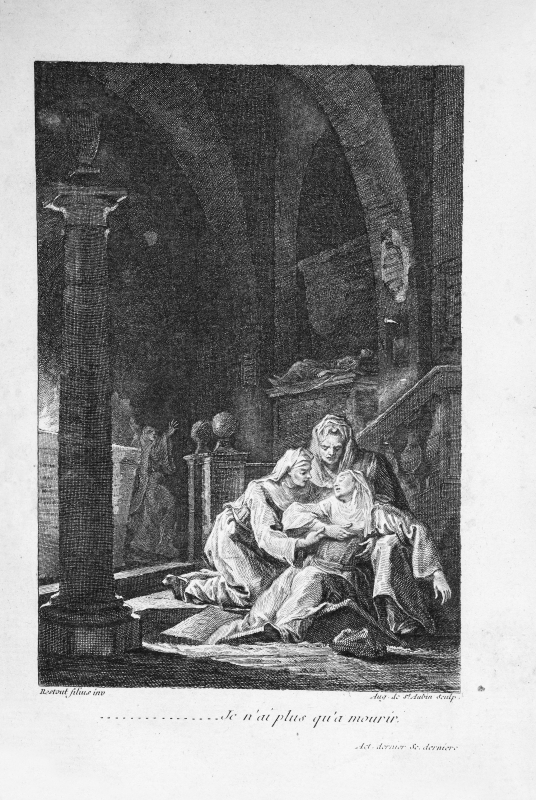

Against forced vocations: frontispiece by an unknown engraver for a play by Baculard d’Arnaud, Euphémie ou Le triomphe de la religion, Paris, Le Jay, 1768: “Je n’ai plus qu’à mourir…”

© Private collection

Anti-monasticism and head stripping in a revolutionary period

A growing section of the public was hostile to “cloistered” convents, as evidenced by the decline in the number of women taking religious vows in the eighteenth century and, as early as 1790, the unveilings, voluntary or, more often, compelled, of nuns that accompanied the Civil Constitution of the Clergy of July 12, 1790. Its preliminary consequences and its aftermath included the suppression of vows and the opening of convents in February 1790. The ensuing scenes – real or fictitious – of semi-lynching in the months that followed (verbal attacks, veils and whimples torn off, so-called “patriotic” spanking), included brutal expulsions from the convents, which were officially closed in the summer of 17924.

As a result, nuns left on a quest for a new asylum and sufficient income, some of the recalcitrant ones were imprisoned, others fled to hiding places or exile. These events forced them to abandon the “habit” and its distinguishing mark par excellence, the veil, which included a head-band and a whimple, the which hid a woman’s forehead, neck and, sometimes, chin. In Christianity, this head-dress is, for such women, “the mark of subjection to their Eternal Spouse” and “the wall of separation” intended to “hide them from the eyes of men” to “live only for Him”, this Christian God, who is an Absent with invisible piercing eyes. Even in monacologies – a literary genre parodying the typologies of the natural histories of moribund animal species for de-Christianizing purposes – the head covering of the nuns is a capital feature, in both the literal and figurative senses, even when described with satiric intent:

The female [monk] differs from the male only by a veil [my italics] that she always has on her head; she is cleaner, does not come out of her house. [...] The female [Benedictine] hides her forehead and her cheeks under a white veil below, black above; she also covers her breast with a white cloth. Both sexes offer a large number of varieties; and we exhort the naturalists who will be in a position to examine them in their own habitations, to give us the characteristics essential to each of them. [...] The female [Capuchin] has the black upper veil, the white lower ; one and the other almost heart-shaped on the forehead; the neck collar ; the white breast wrapping. [...]5

Once the nuns became “citizens”, those “ci-devant nuns”, had to make difficult clothing choices to avoid suspicion. Most of them seem to have viewed their change of wardrobe as “a cross” to bear and considered it a step towards martyrdom. Let us not forget, indeed, the trauma represented, especially for the older ones, by the abandonment of the relative comforts, both physical and spiritual, of a “regulated” community life : a Rule governs such a life down to the smallest detail, including clothing. Not only did these women, now poorly remunerated by the state, have to work to earn their bread, “queuing” to stock up and, worse still, to go several days in a row without receiving communion. Finally, a sign of all these setbacks, they must wear “clothes of derision”6.

It is far from certain that French historiography has measured the violence, at least symbolic, undergone by women of faith, brutally forced to give up the obligations, to which they had freely consented, of the feminine conventual life : confinement, self-effacement, submission, silence, veiling of the body (and its postural and psychological effects), but also practices of piety, spiritual quest, intellectual life. Thus it is that when, in 1790, the superior of the Christian Union of Poitiers, Louise Baron de La Taillée, refuses to join a community of the same order in Munich, she explains her refusal to those who had invited her: “Breaking the commitments I have freely and by choice made to God, that’s what I will never do. I gave him my word for life, my dear Solitaire. I would be very guilty and despicable if I failed to keep it.”7

When the convents are closed, the same Christic vocabulary caracterizes the transfer of certain nuns to the prisons (and sometimes the guillotine), the more distant odysseys (England, Swiss, Germany or Poland) that some undertake and the less dangerous retreat to the shelter of their family8. For all those forced against their will to enter the outside world, the moment of rupture comes not simply when they exit the convent but when they must then remove their veil and come to light. As a result, crossing the threshold of their “home” is the only border they know how to, and feel that they must, describe at length9. For the visitadine and future Trappistine, Gabrielle Gauchat, the expulsion is a “threshold of writing” (G. Genette). On September 29th 1792 she started a journal that ends on June 29 1795, when churches were reopened to worship, then adding only a few pages or lines from time to time10. But in this saga – one of the few told from the point of view of someone who suffered the agony of choices presented even by an everyday wardrobe –, to change one’s clothes is presented as a major and traumatic transition.

This at any rate is what is related by Helen Maria Williams (1761-1827), a writer both English and Protestant, as well as by other indirect witnesses. When incarcerated during the Terror in the former convent of the Dames Anglaises of the Rue de Charenton, Williams coexisted there with nuns who had succeeded in preserving their costume in prison until an order of Mayor Pache on December 8, 1793, forced them to abandon it.

The convent resounded with lamentations and the veils, which had to be abandoned, were bathed in tears. In a few hours, the long trailing dresses were transformed into skirts and the fluttering veils into cornettes [plain linen headdresses]. A young nun asked if it would be possible to arrange her cap so that it completely hid her face ; while another, whose heart had not yet fully ratified her renunciation of the world, let us know that she would see no objection to the grace of her new cornet being enhanced by a cockade11.

Although the prohibition issued against religious veils was seen as liberating in the eyes of the civil authorities who imposed it, for the majority of these women, it was a source of suffering and atonement.

Abandonment of male and female crapes from mourning

Could not we say the same about mourners among the laity who might no longer be seen, veiled by long black crêpes, in the funeral processions? Their clothing, already difficult to identify in the scenes of funeral corteges during the Ancien Régime (the clergy is over-represented and women are still massively absent), cease to be depicted after the celebrations of 1789-1790 and seem to have become socially reprehensible and therefore unworthy of representation, consequently our evidence on this matter comes mainly from a few official pronouncements and engravings. Thus on February 21, 1795 the Protestant lawyer Boissy d'Anglas (1756-1826), deputy of the Ardèche to the Convention, declared: “You will no longer have to put with your roads and publics squares being blocked by processions or funeral groups”12. As for the contributors to the contest, organized by the Institute of Sciences and Arts in the year VIII “on matters relating to funerary ceremonies and burial sites,"they also advocated, for the most part, the abandonment of “hideous and depressing processions” and they even stated their desire to limit or even eliminate all expenses related to funerals13. The summary report of this contest nevertheless accepted the idea of leaving to “the choice of families [...] the outward signs of affliction”, proof of a need for accommodation between the traditional modes of mourning and the position of the egalitarians in favor of reduced religious practices and the wearing of simplified, non-ostentatious and non-specific civil costumes14.

Revolutionary iconography available today shows that the figures of deuillants, present in late medieval art and on many engravings of princely or bourgeois funerals from the Ancien Régime, slowly disappear: those by Abraham Bosse (1604-1676) and Bonnart at the end of the 17th century, and those of sumptuous royal ceremonies15 reflect this trend. The presence of men dressed in large, ample coats, often with trailing skirts, probably black, their heads covered with broad-brimmed hats, the crown of which had either pinned to it or round about it, a crape veil, more or less long, semi-transparent and set backwards, may be noted in most16. Their dress was not totally uniform, as was the case of the hooded mourners of the late Middle Ages, but their clothes (as with their dignified and restrained look) clearly distinguished them from those who were not mourners. This fashion, a proper funerary attire that was visually close to the female ritual garments worn during the time of mourning, lasted at least until the first years of the French Revolution. However, it seems that it quickly disappeared afterwards. Mourners with long mourning dresses, frock coats or traditional long gowns, may still be seen in caricatures of imaginary funeral processions, as they are in representations of the “pantheonizations” held in 1789-1791 in honor of Voltaire and Mirabeau. But there were no more veils seen during “glorious” ceremonies in honor of Jacques Simonneau on June 3, 1792, the mayor of Etampes who was assassinated, or of Marat on July 16, 1793. Even before the massacres of September 1792, public demonstrations of Catholic worship of the dead were limited or prohibited. Black had become suspect and, with it, every way of hiding or disguising one’s face and appearance. The fear of subversive royalist designs, mourning the deposition and then the death of their monarch or hatching dark plots, caused the ban of carnival masks17, veils of mourning and, in particular, the sort of veil that dropped down over the face (that is a veil properly understood), traditionally worn by women plunged into affliction, whether due to the death of a loved one or of Christ on the cross18. Because the veil, funeral or not, also serves as a screen (an obstacle with regard to others and a magic lantern on which to cast fantasies of conspiracies, then and now), it was banned, without being explicitly forbidden, during the revolutionary decade.

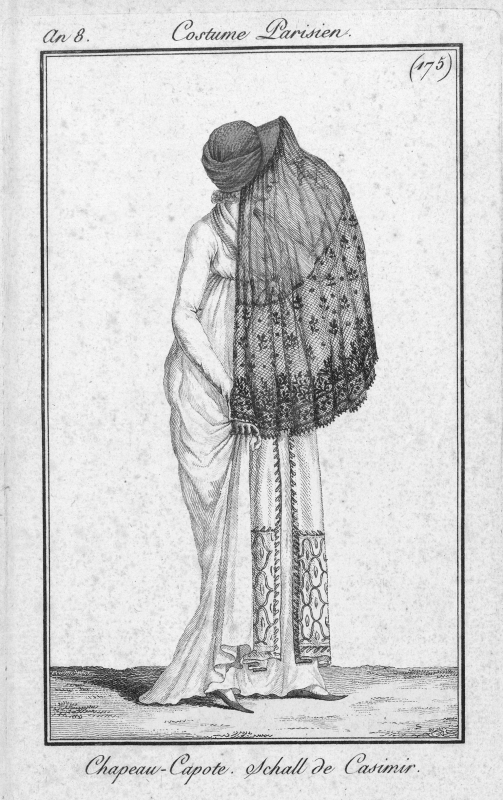

Fashionable religious nostalgy? “Chapeau-capote”, Journal des dames et des modes, year VIII, (n°175) et IX (n° 301)

© Private collection

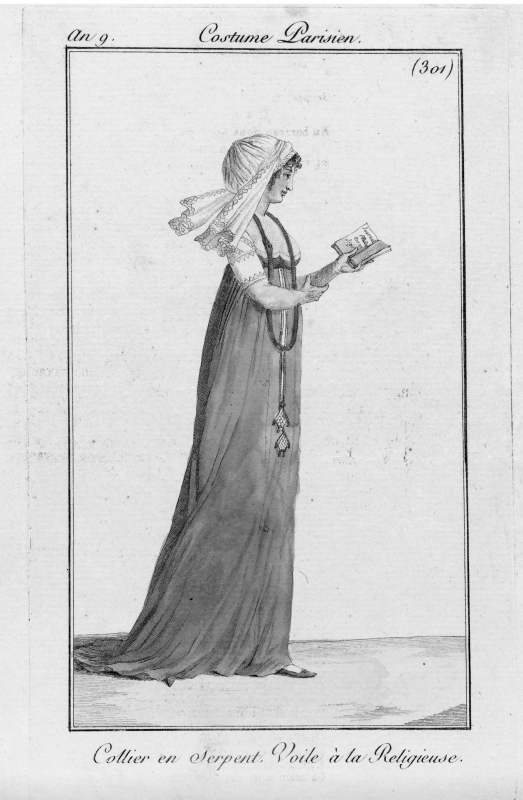

Fashionable religious nostalgy? “Collier en serpent. Voile à la religieuse”, Journal des dames et des modes, year VIII, (n°175) et IX (n° 301)

© Private collection

After 1800, this period progressively ended with the Concordat, the efforts by the Catholic Church to return to Christian beliefs and values, the apparent repudiation of certain achievements of the Revolution, the return to the pomps and circumstances of court (imperial, then royal). A resurgent visibility of “mourning” and religious clothing was the corollary of these complex political and cultural reorganizations. However, the rebirth was not uniform. It had the peculiarity of being gendered and unequal: grandiloquent in women, who became the “showcases” of their companions and of a zealous and more than ever hierarchical Church, this revival hardly concerned men leading a secular life. For them, by the end of nineteenth century, the usual sign of mourning would be a simple armband or a piece of black grosgrain ribbon on the lapel of the jacket (called crêpe)19.

The disappearances, constrained and temporary, of the veils of death (for nuns, a sign for being “dead to the world” ; for the laity, the death of an actual person), under the Revolution, would give birth, paradoxically, to new modes of head covering, most significantly by the voluntary adoption by women of all classes of the scarves once worn by proletarians and now used for purposes of camouflage or, in some cases no doubt, of freedom from a socially imposed identity. These scarves combined modesty, versatility and even elegance and, even while recalling the existence of some earlier or established fashion, they point out the existence of non-fashions, invisible or forgotten, although very widespread. The square of fabric, whether it is coarse, fine muslin, Indian and even lace, was easily tied to hair or could be placed on top of a cap by pins or by one or more knots (under the neck, on the nape or above the forehead). It is a common and convenient head covering and a well-known ornament, before 1789, worn by migrant Savoyardes of the Ancien Régime, women from Arles, Caribean slaves and fish-sellers of Paris.

Two kinds of regional styles of scarves for men and women: “Gascony and Santo-Domingo”, end of XVIIIth century, Encyclopédie des voyages, contenant l’abrégé historique des mœurs, usages, habitudes domestiques, religions, fêtes […], drawings by Labrousse, Paris, Grasset de Saint-Sauveur and Deroy, 1796.

© Private collection

The Proletarian Veils. Marks and Masks

It is difficult to know the hairstyles of the women in revolutionary France despite the abundance of images that seem to present them accurately. Headdresses with or without cockades, Phrygian caps and men’s round hats, handkerchiefs knotted by both sexes on unpowdered hair, populate the genre paintings, the portraits and the propaganda engravings that survive from these times20. But these representations, caricatural or favorable, mainly depict Parisians and the wealthy classes, and often ignore the poor and the Provincials. Nevertheless, despite notable exceptions (David for instance), they underline the disappearance, for rich women, of the big aristocratic hat and its replacement by non-ostentatious linen, used in more and more imaginative ways by their owners in person as linen-drapers and sellers of fashions became fewer.

On may note in passing two striking gender caracters. The first concerns the meaning to be given in the revolutionary imagery to women in hats: Charlotte Corday may here be seen in the company of other more or less fantasized “amazons” whose practices are viewed as being too “virile”21. The second trait relates to the rituals of judicial execution: in front of the guillotine, the male heads are always depicted naked, whereas the women, despite their shortened hair, seem to remain covered in the carts that take them to the scaffold. “Veiled” therefore to death’s doors in accordance with the Pauline injunctions inherited from antiquity: the woman who is respectable (or wants to be) should never show all or part of her hair. But if, in a revolutionary period, the tradition of covering the head remains, with a few exceptions, equally powerful factors were at work to change the appearance of this essential marker of modesty. The double necessity of a seeking of anonymity and maintenance of “modest” distinctions leads to the endorsement of a drapery-knot-turban of proletarian origin. The author who signs himself/herselself as “Marquise de Créquy” (an artful inventor or a ghost-writer, since her memories are largely apocryphal) describes the widespread adoption of the handkerchief in all circles during the revolutionary period as a universally recognized practice:

[the women of the people] have become accustomed, not to comb their hair, but to wrap their heads with a cotton handkerchief. Before the revolution, all of these women of the people, from the flower-sellers to the ragpickers, were wearing a cap of starched canvas, sometimes of batiste, but without lace, and most often of unbleached canvas, for workers' days.22

A “handkerchief” indeed – a more or less large piece of light textile folded into a triangle – can easily be used as a cache-misère, political mask and / or identity mark, especially since, in various forms, it is an accessory, traditional and so far unremarked, of proletarian and provincial fashions. Its use and its diffusion are not easy to detect because, when viewed outside the framework of “picturesque” values, these “marmots”, “handkerchiefs”, “fanchons” or “fichus” (a revealing semantic blur) are said “common” and vulgar. Writers and male artists very seldom chose to represent them in their books and paintings23.

Portrait painters, then as at other times, favored festive dresses and were drawn to elaborate costumes and head-coverings, as they generally embellish the features and the complexion of their models. As for the early ethnographers, they most often concentrated on unusual features, so as to condemn them, or they merely did not describe them. An exception, however, was the business traveler, François Marlin who, very attentive to regional appearances, compares, during a trip from Bayonne to Clermont (Puy-de-Dôme) carried out in April 1789, the costumes of the women of Auvergne to those from other provinces. According to him, the “handkerchiefs” of Auvergnates [mouchoirs] are without any grace and originality since they are found in other provinces:

Their costume is a little heavy; and yet the one worn on feast days Is not unbecoming: it is a whaleboned corset covered with woolen or silk fabric with a skirt of the same material; the two armholes are marked in front and behind with two velvet bands of contrasting color; the ends of the sleeves are decorated with the same bands. These women, sometimes, wear a flat cap or a kind of round bonnet under a mouchoir tied in the Bordelaise style, and hanging down with its points at the shoulders; those who have some desire to please, girls who are looking for a husband or a lover, in Clermont as in Bordeaux, wear such a hairstyle. I have noticed that, in the southern parts of the kingdom, these mouchoirs are used in various ways, but never in ways of flattering to the face, except at Bayonne; only Basques know how to give grace to this unattractive hairstyle. [...]

[On his way to Hainault in June 1789, he adds that] women, here as in Flanders, wear a mouchoir on their heads that they tie under their necks with very little art. This displeasant custom is too common in France.24

The diffusion of this convenient but not without social significance hairstyle (that of the proletarians, at least in the nineteenth century) may thus be taken as established, even though one finds it depicted mainly in the Midi. Yet the Provençales, Bordelaises and other Gascony women portrayed by painters such as Arlesian Antoine Raspal (1738-1811) or the cosmopolitan traveler Jacques Grasset de Saint-Sauveur (1757-1810), and perhaps even the Basses-Bretonnes sketched by Olivier Perrin (1761-1832) in his Breton gallery25, the beautiful Corsicans admired by many French officers in the years 1770-179026 and the Alsatians dear to the engravers of the late eighteenth century27? Should we not add to these provincial subjects, chosen not least because they were relatively well off, the slaves, men and women of the West Indies, compelled to adorn their heads with simple “rags” which more affluent, generally those who had been freed, would transform into what would later be known as madras high head-scarves or turbans28?

The durable or episodic use of a handkerchief to protect and beautify oneself deserves careful study that would focus on the forms, lengths, materials and symbolism of identity (sex, class, race) of these individual head wraps. They are always political, an idea with which some are not entirely pleased29. Long before the poor peasants dear to the realists of the second half of the nineteenth century (Millet, Courbet, Pissarro, Roll and others), the workers on land and sea wore scarves everywhere in France and even more so in the colonies, though those scarves seem to have remained invisible to all observers. The relative invisibility of such hairstyles (whether they were made of white “linen” or coloured cotton) for those pursuing pre-ethnographical research says much about the unconscious ideological blindness – either reactionary or patrimonial – at the more common and unspectacular ways of dressing in the French hexagon. In focusing on neck ornaments, kerchiefs and snot-rags, conventional histories of industry and commerce have been of little help in accounting for the spread in time and space of head-kerchiefs30. Their use, during the Revolution, by aristocratic ladies and their maids is nonetheless attested by witnesses neglected by celebrated “histories of dress” and their misleadingly selective iconography. The evidence of such use survives now only in certain memoirs and the work of minor portraitists.

A portrait of the famous poet, Fanny de Beauharnais (1737-1813), miniature on ivory, c. 1800

Private collection

The fascinating Memoirs of Henriette-Lucy Dillon (1770-1853), who, by mariage, had become Countess de Gouvernet, then marquise of La Tour du Pin in 1825, is, in this context, an extremely valuable document, particularly for the picture it draws, whether or not entirely true, of her preparations for departing from Bordeaux on her way to American exile in 1794:

Since I was on board, [...] I had not been able to take off the madras kerchief wrapped tightly around my head. Fashion was still superflurous powder and ointment. [...]. I found that my hair was very long, so mixed that [...] I cut it quite short, which caused my husband to be very angry31.

Another case is that of Victorine de Chastenay (1771-1855). After August 10, 1792, her exile took her less far away (Rouen, then Châtillon-sur-Seine) and lasted less long, but like Dillon, she was nonetheless obliged to adopt unfashionable modes of dress. The memorialist writes that, as early as the summer of 1793, in the provinces, “all elegance was banished in form” and she says she was proud of the “simplicity” of her way of adorning her short cut hair with bonnets and sometimes ribbons and natural flowers and she used to wrap up her head as “does every honest person […] with the most vulgar and unpolished manners”32. When she was arrested, her brother made a drawing of her in their Dijon jail. She is without a hat, but the sketch shows her covered with an “organdy veil over a flat cap made of a similar fabric”33. An all-purpose outfit, but still more expensive than the printed cotton mouchoirs that we are able to make out on the heads of some prison visitors during “the Reign of Terror”34. These are the same veils, but in fine white linen, that one sees being worn in the intimate portraits, anonymous or not (Manon Roland or Théroigne de Méricourt), preserved, in addition to the museum Lambinet (Versailles), in several other public and, notably, private collections35.

“The resort to incognito” offered by all veils (and revolutionary scarves in particular) allowed women “not to be recognized” and to preserve themselves from danger, but also to “hatch a plot”, whether a mere romantic intrigue or a political conspiracy36. For the republican traveler Grasset, the veil is a mark, a mask and a wonder. Did it not serve much the same purpose for the women called “les Merveilleuses”, these few fashionistas who created the licentious reputation of Paris after the Terror? Although combining simplicity with the antique, French convenience and exotic seductions, their clothes may not break, as is commonly believed, with pre-revolutionary feminine fashions, their “robes-chemises” and their hats in vestal style.

Head and body coverings worn by a merveilleuse on a rainy day in Lyon (Antoine Berjon, La Merveilleuse aux pommes, pencil drawings on paper, c. 1800, B 514 dépôt Lyon, Chambre de Commerce).

Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon.

Head and body coverings worn by a merveilleuse on a rainy day in Lyon (Antoine Berjon, La Merveilleuse au pied nu, pencil drawings on paper, c. 1800, B 514 dépôt Lyon, Chambre de Commerce).

Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon.

Non-Religious Veils. Little White Dresses And Femininity Regained?

For obvious reasons, transparent head coverings have drawn less interest than female bodies “unveiled” by high-waisted dresses with short sleeves and deep cleaverage that would make up the French wardrobe under the Directory and after. The world of commentators-censors-voyeurs supposedly brought into being by the dissolute morals of the Revolution, took great pleasure in denouncing the shamelessness of mostly white outfits, inspired by antiquity and cut in lightweight fabrics that allowed neither rigid corsets or pockets attached to the belt under the skirt37. These same moralists, whether using pen, brush or chisel, portrayed their rich contemporaries as having come up with other transgressions like short, unpowdered hair and they would mockingly exaggerate the size of their headgear (linen caps, high bonnets and tiny hats with a peak38). In doing so, they directed public attention away from another fashion – very modest and more banal – that of the veil. A fashion in which memories of far distant times and places seemed to blend: Corsica and its Mediterranean modesty, the Caribbean and their supposed Afro-American “nonchalance”, the Vestals of antiquity and of recently deposed Christianity39, etc.

Returning to Paris in 1796, Victorine de Chastenay marvels at the transformations of Parisian fashion and emphasizes several facts neglected by the “historians of dress and costume”: the disparities between Paris and the provinces, as well as between the different social circles of the same district in the capital. In doing so, she brings to light the significant differences in the images that recur in a small number of “fashion caricatures”, a category that remains to be clearly defined and that includes everything from satiric plates, hostile to change, to illustrations from collections such as the Costumes parisiens or the Journal des Modes. But these engravings, as we know, seem to be fancy pieces of imagination and models rather than actual clothing. The memoirs of the period, even if their reliability is uncertain because of their belonging to a diminished and nostalgic world of a bygone era, reveal the complexity of the headware of posh women:

Paris offered a singular spectacle. It was a triumphal moment for the Chaussée d'Antin; a time when Madame Recamier, renowned for her beauty, pretended to be wearing a linen scarf, always placed in the same way. The young people who were born under the Old Regime followed this kind of elegance and luxury at a lower level and all the more because it could be arranged with very little expense. The young men had their hair cut à la Titus; the women drew inspiration for their hairstyles from antique statues. A light chiffon with a bow or ribbon was an exquisite ornament, and only dull older women did not fail to powder their hair, to have pockets and to wear shoes with big heels. [...] everything seemed so theatrical [...] I was so provincial that I had an extremely difficult time getting used to it.40

This fashion, celebrated by all those who burnt incense at the altar of Juliette Récamier (1777-1849), was unknown before the consular and imperial period whereas it is a distinctive emblem of female style during those decades. At first Parisian, then provincial, the vogue of the veil is visually well documented but little analyzed, except as recorded by such collectors of anecdotes as John Grand-Carteret (1850-1927) or a recent historian of handbags: on a engraving from the series called Costumes parisiens, number 67 shows a woman, haughty in her bearing, dressed in thin fabric and accompanied by the legend “Iphigenia’s veil. White mantlet. Purse with a motto”41. Her head covering may be seen as a kind of counterpart to the cotton head scarf worn by women lower on the social scale, as the author of the apocryphal memoirs fastened on “Marquise de Créquy” tells us42:

Cashmere shawls and veils of lace are the two things that distinguish women of a certain kind from the others. The women with shawls and veils have replaced women with baskets from yesteryear.

The success of the veil must be understood in relation to (which is not to say that it is explained by) several phenomena: the general simplification of European clothing since the 1770s, “anticomania”, the taste for and the increasing avaibility of light and transparent fabrics, the elongated outline of the female figure and a corresponding reduction on the volume of hairstyles and headgear, trends that may have been accelerated by a general movement toward “reform of dress” (as well as of manners), the increased emphasis on frugality in public display, the emigration of the fashionable ladies (and their seamstresses, wigmakers and hairdressers). An elegant woman now aimed at being vestal, odalisque and / or republican43.

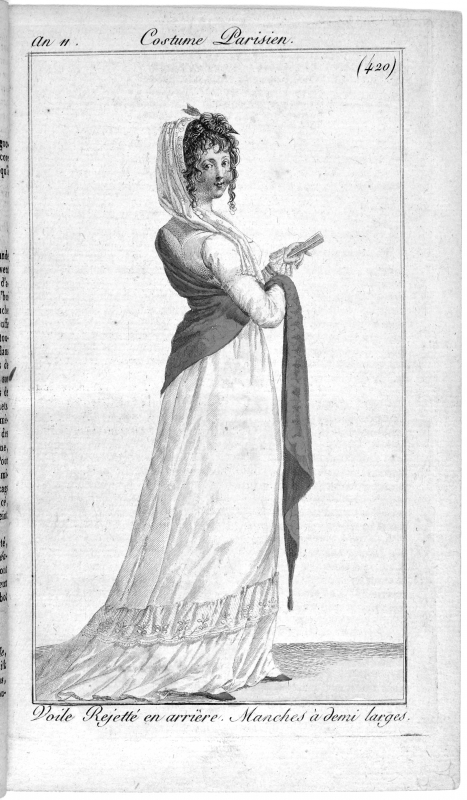

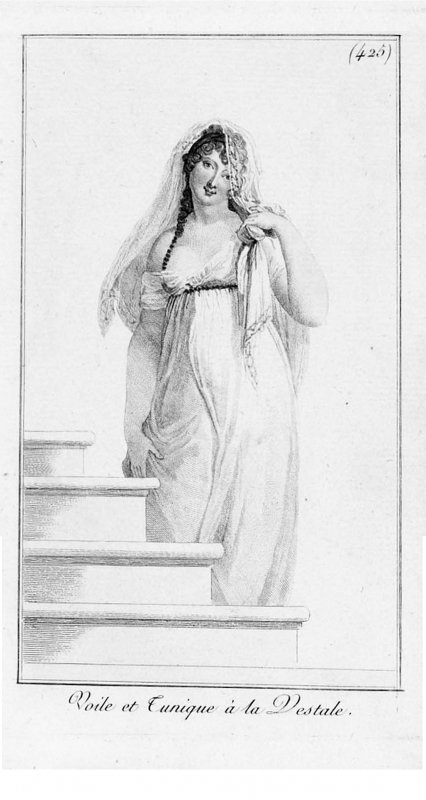

Veil after the antique. “Voile rejetté en arrière. Manches à demi larges, Journal des dames et des modes, year XI (n°420)

Private collection

Veil after the antique. “Voiles et tunique à la vestale [Juliette Récamier]”, Journal des dames et des modes, year XI (n°425)

Private collection

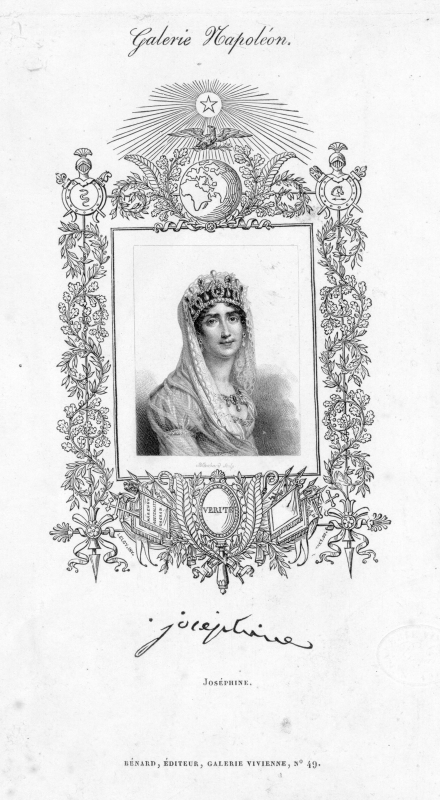

With the exception of veils made somewhat later for the Empress Marie-Louise in 1810, we do not know the exact cost44 of the luxurious muslins and cobweb-like gossamers that were popular for two or three decades among fashionistas such as Juliette Récamier, the famously beautiful wife of a banker, as well as the women of Bonaparte’s entourage and other “grandes dames”. Several portraits of Juliette Recamier, including one painted in 1801 by Jacques Augustin, show her sitting wearing a semi-long white veil, the edge of which is held in her right hand in a pose taken from a painting by Richard Cosway: Juliette, with loosened hair, poses upright, her face half hidden under the same white muslin45. Other veils, equally virginal and transparent, were used during the same period among women in Napoleon’s family. This is the case, for example, of Josephine de Beauharnais in a portrait painted by Gros in 1805, or in the genre scene entitled “The Empress Josephine surrounded by the children whose mothers she rescued” (painting by Charles-Nicolas-Raphaël Lafond, 1806, Dunkirk Museum)46. Sitting dressed all in white in the middle of grateful toddlers and pregnant women, the Empress is the only bright spot: she shines in the middle of a dark-robed female crowd, thanks to a long semi-transparent veil, placed high on her chignon. In contrast, the other visitors around her wear hoods and have their hair down.

But it is the mother-in-law of Josephine, Maria Letizia Ramolino, (1750-1836), who is the most willing to be painted with a veil. Like an old memory of the Corsican long traditional veil called mezzo and / or of a fashion in vogue when her son came to power, “Madame Mère” did not stop fastening to her hair, her diadems or her turbans, light fabrics that floated down over her shoulders and her back. As for the clients in white outfits of the young Ingres, such as the Countess de La Rue (private collection) or Madame Rivière (Louvre Museum)47 in 1804, they are draped in fine muslin that poeticize their face while leaving it visible. In that same year, popular imagery, whether pro-bonapartist or not, found itself able once again to proclaim the virtues symbolized by a white vail on a female body to celebrate the magnanimity of Napoleon and the grandeur of an aristocrat ready to humble herself to obtain the pardon of a hus band sentenced to death on June 9, 1804: Armand de Polignac, who was involved in the Cadoudal trial48. On the other hand, the Comtesse de Lavalette, born Emilie de Beauharnais (1781-1855), would come to regret having worn a hat ornamented with feathers rather than a veil during her visits to her husband incarcerated by Louis XVIII after the Hundred Days: the latter’s incredible escape disguised as a woman with his wife having taken his place in the cell would have been greatly facilitated49.

As always, the veil, fashionable and / or religious, has been able to serve as a means of embellishment as much as of camouflage. Malleable, it is the most “portable” garment and its success at the end of the Age of Enlightenment may be understood in relation to the craze for mobile objects so well illustrated by the multiplication of “flying tables”, “folded harpsichords”, “toiletries”, bags and other “portables"50. As an element of any “primitive” clothing throughout human history (antique and simple, it is reversible and versatile), the veil is also, let us not forget, one of the studio accessories and may be used by artists to demonstrate their skill and to entice their customers. Thus, the veil, when featured in paintings, offers such women artists as Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun or Nisa Villers the means to embellish their models and to create lasting monuments of charm and virtuosity. Occasionally, a cloth that surrounds the head and falls to the bust gives the subject of a portrait an “antique” air, permitting a female portrait painter to be seen as a “History painter”, that is an artistic practinioner of “grand genre” from which women were for the most part excluded. The portrait of Countess Siemontkowsky-Bystry, painted in Vienna by Vigée-Lebrun in 1793, is a good example of this ambition since it succeeds in giving a representation of a Polish aristocrat in Roman dress and of a new Hebe holding her golden cup in her hand51. The bust is draped in a bright red fabric edged with golden leaves, while a thin white chiffon barely covers the head of the model and falls down over light brown curls tied back by a garland of small white roses woven with red ribbons. The translucent fabric, barely visible on the hair, is similarly transparent when it covers the neck. It creates a sense of empty space, it seems to set free from the painting’s dark background, a pensive face that barely tilts to the left, in a manner already visible in the portraits of Marie Antoinette before the Revolution52.

The historic and aesthetic ambition of Vigée-Lebrun is obvious and no doubt suited the requirements of the woman who commissioned it, a wealthy friend and a “woman of the world”. But does she want to disguise herself and / or appear fashionable? An answer is suggested by a companion portrait to this work, showing the husband of the countess as a guitar player with the black mass of his cloak (a Venetian mantello?) barely enlightened by the knot of a white necktie and a red border at his collar, seeming to detach themselves from a background equally empty and light-colored53. To explain why so many “grandes dames” are in their portraits wreathed in veils of varying transparency – whether they are Austrian, Russian, Polish – it is useful to recall the personal taste of Vigée-Lebrun for simple and convenient clothing in her everyday life, at court and even more so in exile54? And, when painting portraits of noble women, she liked to impose veils on her clients even before her departure from France in 1789. In her memoir called Souvenirs, she recounts with great enthousiasm the Hellenic craze that she shared with other painters and her skills as a costume designer55.

Let us conclude with the (presumed) Portrait of Mrs Soustras painted in year X by Marie-Denise Lemoine known as Nisa Villers (1774-1821)56. This enigmatic work is so fascinating that it has been successfully taken over and reinterpreted by a contemporary artist, Marine Renoir, for a famous shoemaker Christian Louboutin. The foreground of the original painting shows a scattering of semi-organic objects (a bench, roses, a pair of gloves that still seem to contain the hands that discarded them). But what strikes us most is the silhouette, depicted against a background of empty sky and deserted meadows with sparse trees, of a young woman dressed in black and semi veiled, bending forward to attach the ribbons of her fine shoes and who mysteriously watches us. The transparent black lace veil that covers her head falls in large folds on the right side of her face, against her rose-pink complexion. This veil, like the pose of the model, is inherited from antiquity. The palette is totally original and its violent chromaticism – the black dress and veil that contrasts sharply with the white of the shirt and the red piping of her thin shoulder straps-turn the young woman into a real persona, a kind of “social mask” where she who poses becomes a character. A mourner, a victim and an object of temptation.

A necessary accompaniment of the new fashions inspired by Antiquity, the veils of the privileged rich, from the Revolution to the Empire, show a new form of elegance, where the restraints of good taste does not hinder the liberty – at least the apparent liberty – of the body. This is a double break with the extravagant rigidities of fashion during the Old Regime and with the imagery of the woman who, bad mother, poor or religious, devoted herself to her pleasures and expenses.

The veil, in a society dominated by male values, permits the exaltation of a conventional image of womanhood. Has it not permitted, in too facile a way, an aestheticization of selfhood in which, projected outward by enveloping fabrics, the virtues of a woman chaste and thrifty, combine the qualities of a seductive spouse and of a mother without personal ambition?