Young girls dresses are not to be taken lightly.

In 1859, a duel was played out at the Seine civil tribunal; a merequarrel of unpaid dues between a couturier and her client. But their lawyers turned the trial into a singular conflict of norms

Sometimes a simple name awakens a dormant history. Such is the case of Gustave-Gaspard Chaix d’Est-Ange, a name stumbled upon during research on masked balls and costume balls in the 19th century. Chaix d’Est-Ange was Flaubert and Baudelaire’s lawyer for the momentous trials of Madame Bovary and Les Fleurs du Mal that occurred in 1857. However, he also unexpectedly appears in the Bibliothèque National de France’s catalog linked to a little-known dressmaker, Delphine Baron, in a case that pitted her against the baronne de Korf, represented by Me (Maître) Léon Duval, held on April 6, 1859 at the Seine Civil Tribunal. In La Tribune Judiciaire. Recueil des plaidoyers et des réquisitoires les plus remarquables des tribunaux français et étrangers, which published both lawyers’ arguments, we see the tangled threads of an fascinating encounter between the French fashion world, a Russian baronne, and one of the most famous lawyers of the time1 The trial may have seemed like a simple “affaire de chiffons” or “clothing case” (Le Journal du Loiret April 11 and 12, 1859). In sum, the baroness refused to pay for the Louis XV flower girl costumes that she ordered for her daughters for the comte de Morny’s fancy dress ball on March 2, 1859, on the pretext that they were “immodest” and delivered too late2. She demanded 3,000 francs in monetary damages. The dressmaker, opposing her claim, demanded payment for the provided costumes. The participants, their arguments, and the context, as well as the case’s immediate echo, all combined to upend the Journal du Loiret’s reductive description of the affair. Investigating the affair reveals a much richer history than expected: a harsh feud over norms at a time when costume parties were never far removed from the world’s pulse.

“Oh! how lovely the trial of Mme la baronne de Korf against Mme Delphine Baron”3

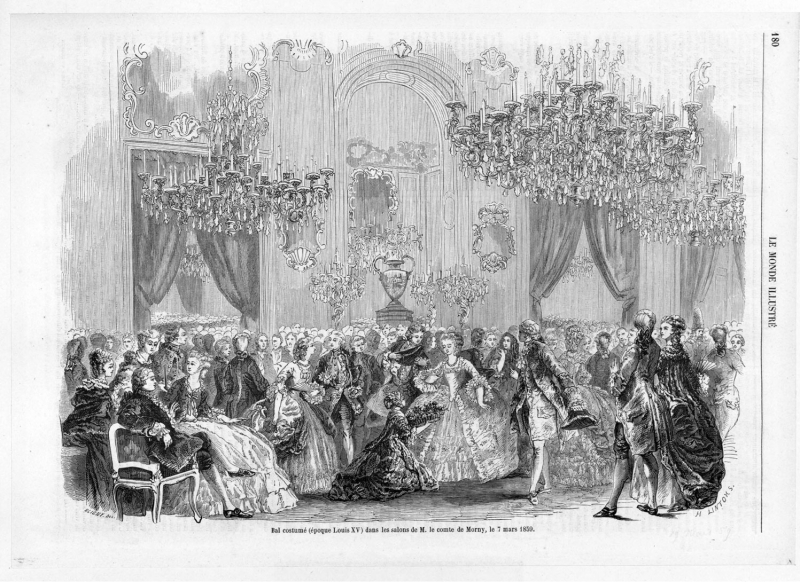

“You know sirs that the end of carnival was marked by a veritable deluge of costume balls: on the 28 of February, the State Minister’s ball; on March 2, the comte de Morny’s; on March 5, the Foreign Affairs ball; and finally on the 7, the impératrice’s; and I’ve only listed the official parties, not to mention the numerous other functions.”

Drawing by Bligny, engraving by Henri Linton ; page from the newspaper L’Illustration. © Private Collection.

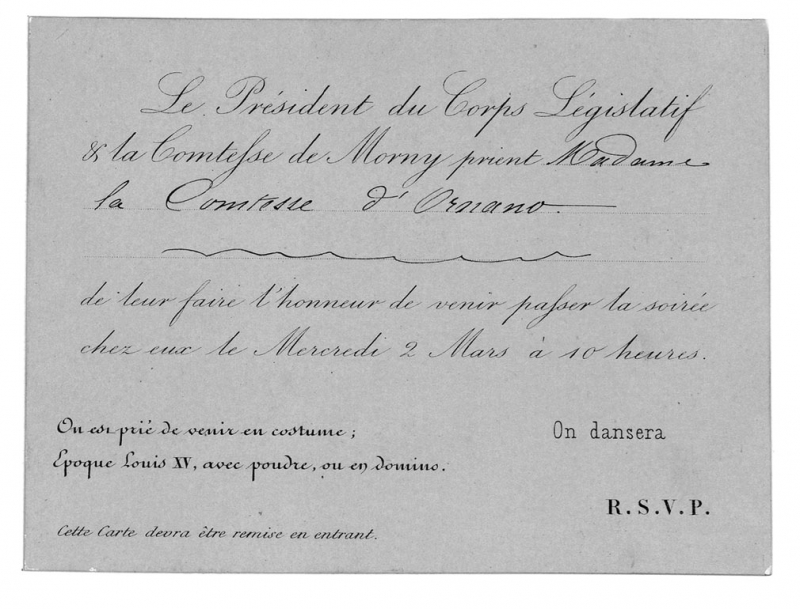

Chaix D’Est-Ange opened his case with this list, emphasizing the singular festivity of Napoleon III’s reign. Costume balls and masked balls weren’t a Second Empire invention – they occurred nearly without interruption from the Restoration to the Années Folles. Under the Restoration and during July monarchy, the duchesse de Berry or Marie-Amelie, Louis-Philippe’s wife, organized costume balls. Yet, they belonged, with a wearying persistence, to a long tradition of aristocratic court parties. During the Second Empire, masked balls became the consecration of a specific form of politics. The balls listed by Chaix D’Est-Ange were private and organized by the circles of power: ministers, state councilors, ambassadors, Napoleon III and Eugénie. They fed a vertiginous social calendar throughout the period, without direct comparison to what came before or after. During the Third Republic, official costume balls disappeared from the political sphere, if not from its salons. Chaix d’Est-Ange cited several great orchestrators of masked balls, including Fould, Minister of State from 1852 to 1860, Morny, President of the Corps Législatif from 1854 to 1865, and Walewski, Foreign Minister from 1855 to 1860. Other famous hosts include Persigny, who organized costume balls throughout his second appointment as Minister of the Interior from 1860 to 1863, and Chasseloup-Laubat, Minister of the Navy and the Colonies between 1860 and 1869, both bon vivants. Invitations to these balls, well preserved at the Bibliothèque-Musée de L’Opéra de Paris, are precious archives that inform us of social codes regarding parties and of the behavior therein. An invitation addressed by the comte de Morny and his wife to the comtesse d’Ornano for Morny’s ball on Wednesday March 2, 1859 noted that guests were expected at the Hotel de Lassay, the Morny’s residence, at 10 pm “in costume; Louis XV era, powdered or in domino cloaks.” These parties were open to the nobles of the Second Empire, such as the comtesse d’Ornano, as well as to European elites such as the baronne de Korf. Princess Pauline de Metternich, the comtesse de Castiglione, and the comtesse Barbara Rimsky-Korsakov frequently attended such balls, all wearing audacious costumes that often revealed more of their bodies than they masked. For Napoleon III and Eugenie’s grand ball on February 7, 1866, the comtesse Rimsky-Korsakov came dressed as Flaubert’s Salammbô – in other words, barely covered. Information on the baronne de Korf is, at first sight, sparse. Maitre Léon Duval’s oral argument gives us only a few clues: she was a “Russian grand dame,” “wife of the général baron de Korf,” who came to Paris from the Russian court, and lived at the Hôtel Richmond with her two daughters. This information opens several trails. There’s nothing surprising with Russian presence in Paris in the wake of the Crimean War, which saw Alexander II break with the isolationism that his father, Nicholas I, had imposed. After a series of political exiles arrived, including Turgenev in 1832 and Bakunin in 1844, others joined – many were artists and traders4. These émigrés reconnected with the socialite habits of the Russian élite, who were used to spending part of the winter in Paris. They preferred the Right Bank, particularly the Rue de Rivoli, the Boulevard des Italians, and the Rue de La Paix. The Hôtel Richmond, on the rue du Helder, was central to this selective and socially significant geography. Moreover, the life and personality of Morny himself further explain these shared sociabilities. He was the Ambassador-at-large to Russia in 1856. In 1857, he married a Russian princesse, Sophie Troubetzkoï. On returning to France, the couple threw frequent balls and receptions where the notables of the Second Empire mingled with artists and european aristocrats.

Le Moniteur de la coiffure, for the Bulletin of Fashion, New York, volume 21, January 1860. “Historic artistic and fancy costumes from the Maison Moreau, Delphine Baron, successor, drapery, waistcoats and major novelties from the Maison Dubois jeune, shirts, collars and ties from the Maison du Phénix. S. Hayen senior, millinery from the Maison René Pineau, haircuts and hairdressing by Loisel. Perfumes from Violet, inventor of Thridace soap, purveyor to her majesty the Empress. Paris, rue des Petites Ecuries, 19.”

© BnF

An unexpected witness, however, allows us to draw a more precise portrait of the baronne de Korf. In the case’s tangled web, a touch of mystery resides in the discovery of the baronne’s great-grandson: Vladimir Nabokov, the author of the notorious Lolita5. Two of the protagonists of the 1859 affair are thus the writer’s paternal grandparents: Marie, one of the baronne’s daughters for whom Delphine Baron made one of the incriminating costumes, and Dimitri Nabokoff (1827-1904), then Councilor of the State6. Almost a century later, their grandson related the dispute of 1859 in detail – “an amply grotesque incident” in his words – and shed light on some its major players. Nina Alexandrovna (1819-1895), his great-grandmother, was the wife of a German-born general serving in the Russian army, Ferdinand Nikolaus Viktor von Korf(f) (1819-1895), with whom she had five daughters. The baroness had come to spend the winter of 1859 in Paris with two of them: Olga and Marie, the oldest, born in 1842. Dimitri Nabokov, a family friend and Marie’s future husband, was also there. At the time of the ball, and of her marriage in September later that year, Marie was 17-years-old, the age that draws the utmost maternal and social vigilance. In a commentary both pointed and allusive, Nabokov adds that his “good great grandmother” was “beautiful, passionate, and, sorry to say, far less austere in her private morals than it would appear from her attitude toward low necklines.”7 In view of these comments, the biting irony of Chaix d’Est-Ange’s plea resonates: “I don’t have to dwell on the fact that a neckline high enough for the evening, you find too revealing the day after, and that this inordinate love for very high neck lines, that seizes you right at the moment of paying the bill […] strikes me as suspect.” This introduces a question that we shall return to: what if the case’s heart lies beyond a simple crime of decency and beyond a dressmaker’s betrayal of the imperative modesty of two young girls?

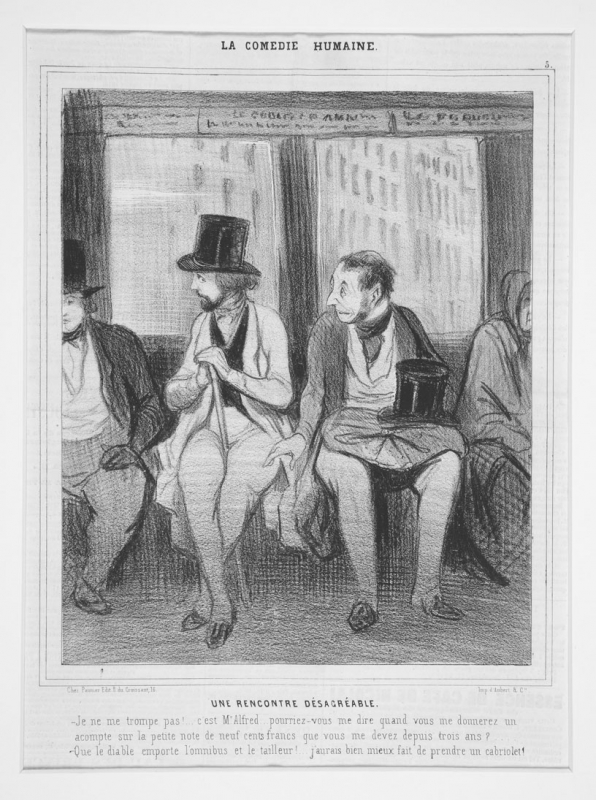

“An unpleasant meeting between a tailor and one of his debtors”

Drawing by Daumier, La Comédie Humaine, published in Le Charivari, April 3, 1843. © Private Collection.

In the battlefield of the civil courthouse, the baronne de Korf came face to face with a figure from an entirely different background: Delphine Baron. Her presence invokes the shadowy world so often forgotten behind the splendor of imperial parties: the petites mains (seamstresses) who sewed and embroidered, made the dresses, bouquets, and ribbons that adorned masked and costumed bodies, and the sewing workshops with their constraints and pressures leading up to the feverish eves of the balls8. An investigation into the life of Delphine Baron – who, as La Tribune Judiciaire states, had “taken the helm, not too long ago, of the famous maison Moreau” – shows that although she is unknown to many today, she was well-known in her time9. Advertisements, newspaper articles, dictionaries, and correspondences show that she enjoyed a certain amount of fame from the Second Empire and the beginning of the Third Republic until her death in July 1895. Yet the Annuaire des Artistes et de l’enseignement dramatique et musical signaled her death with a laconic obituary, which reduced her life and career to the status of “wife of:” “Mme Delphine Baron, widow of Marc Fournier, who, from 1851 to 1868, was the director of the Porte-Saint-Martin theater.”10 More broadly, the “queen of fancy dress”11 is shrouded in silence, stifling the style that she made her own, and practically erasing any memory of her activity. Disparate sources from between 1850 and 1880 testify to a richer history. When she took over the Maison Moreau, in 1856 or 1857, Delphine Baron ended her earlier career as an actress. She was born in Lyon in 1818, came to Paris with her family in 1833, and entered the Conservatoire before debuting at l’Odeon in 1844. In 1845, she married the vaudeville performer Marc Fournier, and en- tered the Porte-Saint-Martin theater in 1846, where her renown as an actress was established. She was famous enough to for the sculptor Calmels to create a plaster bust of her to display at the 1857 Salon. Her separation with Marc Fournier, in 1856, drove her to leave acting. She bought theater costumes from the famous designer Babin and opened her own fashion house12. This choice, catalyzed by her acting career, had roots in her family; her father, a grounds inspector (inspecteur des domaines) and painter, permitted Delphine and her brother Alfred (himself a sculptor before becoming an actor) to receive artistic training. Thus the young Delphine trained in the art of engraving and, for a time, made a career out of it before entering the theater scene. At Porte-Saint- Martin she continued to draw – with great talent according to her contempo- raries – sketching costume designs that she would later execute at her fashion house13. She specialized in costumes – for theater, balls, or artists – as well as in fashionable daywear (toilettes de ville), with apparent success. In the 1860’s her name appeared regularly in newspapers and fashion columns regarding theater or high society, the journalists lauding her creations. In 1860 Le Moniteur de la Coiffure called her “the queen of fancy dress,” poeticizing her most frequent descriptor: that of grande couturière. In 1877, her house was recommended to foreigners attending the the Paris Opera’s masked ball, and in 1878, Le Monde Artiste, raved about the “marvelous” costumes that she created for a stage play in Rouen14. Various sources also link her name to those of renowned artists: in 1863 she rented a Pierrot costume to Theophile Gautier’s son and in 1865 La Petite Revue links her to Nadar:15

« Nadar enters the salon where masses of visitors circle around the windows. A hundred voices greet him in a hundred crossing calls.

- Nadar, don’t forget that we’re expecting you at seven for our Tuesday dinner.

- Nadar, you promised my wife that you’d come to her masked ball tonight.

- Nadar, I need an article from you for my newspaper, about the Amsterdam Ascension […]

- Yes my children, yes my dears, I’m yours, right away, in five minutes, in eight minutes, in a quarter hour… Henri’s expecting me for dinner. Charles, be happy, Delphine Baron just sent me an incredible costume for your ball. Victor, wait for me at five at café Riche.”16

The transfer of her fashion house between 1863 and 1871 from the rue Filles-Saint-Thomas to the corner of rue Richelieu (n°112) and Boulevard Montmartre (n°21) indicates a boom in her business. She became more clearly inscribed in the chosen quarter of reputable fashion houses. (This was before haute-couture designated the rue de La Paix and its vicinity as its beating heart.) Apart from the the 1859 affair, Delphine Baron appears several times in the press for conflicts with certain clients. In 1881 she clashed with a singer, Marie Heilbron, who she accused of damaging her reputation by referring to her costumes as “botched” in her letters.17 In 1886 she underwent a new lawsuit, this time against an actress, Jane Granier, to obtain the payment of over 3,000 francs of breeches. The actress and her impresario were ordered to pay the bill, while a journalist found pretext for irony: “Mlle Granier then has to wear the breeches?”18

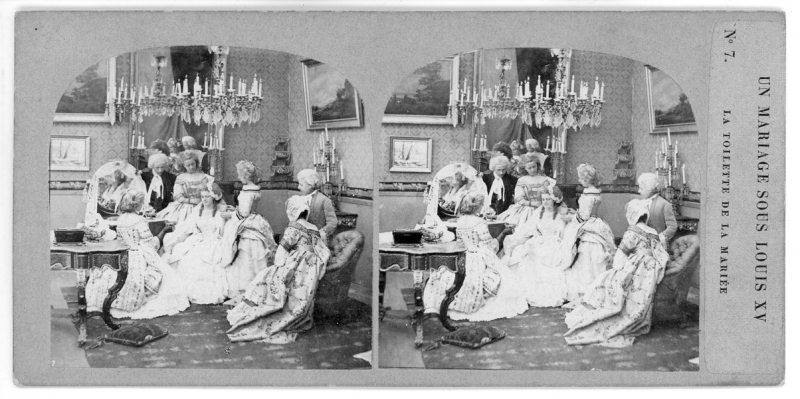

Stereoscopic image. “A wedding under Louis XV’s reign”, 1859. La photographie: journal des publications légalement autorisées: faits intéressants la photographie, annonces, Paris, Furne fils et H. Tournier, managing owners, May 1859, pages 3-4: “This little series of stereoscopic pictures that the Maison Furne fils & Tournier has just released is distinguished by the opulence and precision of the costumes (from the maison Delphine Baron), by the elegant composition of the groups, and, above all, by the processing of the prints, which can be compared favourably with the most accomplished and succesfull works of English photography.”

© Private Collection

Delphine Baron encountered a number of stiffers and debtors during her career. Literature has a rich history of portraying this inevitable facet to a tailor’s career. In the 17th century Molière created the arguing duo of Monsieur Dimanche, a tailor trying in vain to be paid, and Dom Juan, his devious client. Artists of the 19th century sketched this scene often enough to make it a cliché. Couturiers and non-paying clients were thus inseparably linked through novels, in particular Balzac’s La Comédie Humaine, physiologies, theater, and caricature19. A good example of this genre can be seen in Daumier’s incisive painting – “a disagreeable encounter between a tailor and his debtor” – which appeared in Le Charivari on April 3 184320. If the cliché is an old one, it gained new life in the second half of the century. The dueling pair was no longer just a literary and artistic subject, but a real one that appeared regularly in newspaper columns and legal reports, becoming, in a sense, a duel of the courts. Trials opposing couturiers and clients grew increasingly frequent. And so the accepted norms relating these two worlds – depicted in art as the client’s condescension for his tailor, the debtor’s bohemian negligence or pecuniary carelessness – was more firmly contested by couturiers who no longer hesitated to take their clients to court21. A new context, entailing the rise of harsh commercial stakes, allows us to understand this development. Competition heightened between emerging stores and large established ones; the hierarchy deepened between the emerging sector of “haute-couture” and the flourishing trade of made-to-measure garments.22 At the same time, we see the rise of a social conscience regarding the petites mains and larger figures of the fashion world. All these elements combined to mould the cliché into legal reality.

“What is then this event of the day and why so many high emotions among fervent fashion disciples?”23

The subject of the “event of the day” seems simple. The actual case, on the other hand, is rife with complications, entangling a dozen protagonists in a hotel suit: the baronne de Korf; Nabokof, the family friend; seamstresses; the studio’s première demoiselle (head assistant); a rival couturier of Delphine Baron; two bailiffs; some witnesses; and a police officer. We will begin by following Me Léon Duval’s account of the events. Having received the Mornys’ invitation in February, the baronne decided to order three costumes – one for herself from the maison Delille and two for her daughters from Delphine Baron. For her daughters she wanted costumes in the style of Louis XV flower girls and gave the designer an engraving as model. She arranged her order for 9 pm the night before the ball. Her costume arrived in time but those for her daughters were late. They were finally delivered at 9 pm, the same evening as the ball, without the flowers that she asked for, which were promised to arrive 15 minutes later. Here the major grievance arose – the costumes were “immodest,” without taste or style, made of cloth where silk was expected. They disappointed and shocked their purchaser. Delphine Baron was immediately warned and sent two workers to make modifications which “instead of fixing them, rendered them even more unacceptable.” The baronne then sent for Mlle Fourtunée, couturier of the Maison Delille, who judged the costumes “incorrigible.” At 11 pm madame de Korf decided that her daughters would not attend the comte de Morny’s ball. The next morning matters intensified when the baronne officially and legally documented her refusal of the costumes. The day after that, Delphine Baron sent a bailiff to her client’s hotel to seize 700 francs-worth of goods. Dimitri Nabokok, on the premises, proposed to pay the 700 francs instead: the bailiff refused and ordered the seizure of goods, proceeding “without the slightest civility.” A second bailiff was then sent. Instead of diffusing the situation, the second bailiff counseled advised “resisting the seize if one must.” A policeman was then called as backup, which permitted the momentary resolution of the affaire. The first bailiff finally accepted to stop the seizure of goods in return for the 700 francs, which were handed to the police officer. Me Léon Duval then demanded that the costumes be returned to Delphine Baron and the 700 francs returned to the baronne, as well as monetary damages.

Me Chaix d’Est-Ange reacted to this account with harsh mockery: “I don’t know if it’s because this trial is on the subject of a ball that Mme la Baronne de Korf thought it proper to dress up the facts in such a strange manner.” He gave a remarkably different version of the affair, not in its larger arcs, but in the interpretation given to the protagonists’ behavior. Both oral arguments, taken together, pit social conventions against the rules of the game (or of the ball), and aristocracy against the fashion world, as well as the Ancien Regime against the new society.

“The bodices were too low-cut: I understand the full gravity of such a reproach made against a bodice.”24

The first conflict of norms – the apparent heart of the trial – played around the presumed indecency of the costumes that Delphine Baron provided to the baronne’s two young daughters. Me Leon Duval declared at the trial’s start that the costumes were “immodest,” too revealing, and too tight. He thus established his stance on the social norms that codified how young women of good standing were supposed to dress. These norms were dominated by imperative decency and the fundamental virtue of “modesty” that commanded girls to avoid wayward glances, be inconspicuous, show restraint, and reassure future husbands. The strategy was matrimonial in objective. The archetype of the modest young girl was reinforced in the 1860’s when newfound emphasis was placed on the chastity of women in their roles as girls, wives, and mothers25. This fed into broader moral policing under the Second Empire, as exemplified by the Madame Bovary trial. The prosecution, under Ernest Pinard, railed against “the poetry of adultery,” with its “lecherous scenes” and Emma’s inappropriate lust. This kind of prudishness was often protested. Baudelaire, for instance, jokingly referred to “the grapeleafs of Sir Nieuwerkere,” a reference to Napoleon III’s Minister of Cultural Affaires who known for covering up naked statues. Astolphe de Custine was equally critical, writing, “Our puritans in black robes obstinately want to make this world a convent for the education of young girls.”26

Dress codes of decency rigorously followed the stages of life: for young women, dresses were to touch the ground and their hair be made up elegantly; for “young girls”, skirts could reach the ankles and hair could be braided or pulled into a bun; for little girls, dresses could reveal their boots or pants (“modesty tubes” according to the highly indicative language of the time) and loose hair.27 Sartorial norms were also imposed for balls, which, in the words of the vicomtesse de Renneveill, “had enormous influence on the contingencies of family and social life.”28 The goal of dressing for a ball was to seduce while respecting the norms of decency, to show one’s social rank without ostentation, to basically discreetly seek a husband. Mothers saw to their daughters’ outfits with extreme care. Léon Duval reminded his audience: “a mother must supervise dressing at such a time and have the ability to make modifications.” Chaix d’Est-Ange didn’t contradict this in his argument, saying, “the bodices were too low-cut; I understand the full gravity of such a reproach made against a bodice; I understand that a bodice betrays its duties when it doesn’t fulfill the expecta- tion of modesty that it’s tasked with.”

It’s only in the 19th century, marked by the legibility of the social body, that clothing is, before everything, a sign an immediate translation of status, age, and sex. Me Duval resumed, “we are in this world, a serious man or a frivolous one (évaporé), a respectable women or a women adhering to all nuances of Parisian society, depending on way that one dresses. What in Latin was called habitus corporis, the way of being, depends on the way we present ourself.” He implicitly stated that for a young girl to expose her shoulders and breasts to the gaze of others would relegate her immediately out of graces of good society.

Different sartorial norms, however, had been in place for women of the Second Empire. The impératrice Eugenie made low necklines the fashion for ball attire, starting a vogue that stretched from evenings in Compiègne to the Tuileries. At every age, then, a way of dressing, but for every occasion too: low necklines would be indecent for morning wear but were obligatory for the evening dresses of every grande dame of the Second Empire29. It is impossible, then, to read the 19th century in terms of a general prudishness: norms of decency were socially marked but also context based – depending on the activities being undergone, on the time of the day, and on one’s age. These norms also intrinsically fed a particularly fertile erotic imagination focused on what propriety imposed, whether by containing (hair) or concealing from view (ankles).

Léon Duval’s trial on immodesty led to a number of problems. Chaix d’Est Ange spiritedly picked up on the first, presenting the engraving of the Louis XV flower girl costume as evidence: “it seems that under Louis XV, this is how flower girls dressed, or rather… undressed.” The baronne de Korf’s choice is indeed intriguing since this costume was characterized by a very low neckline and a short skirt. The engraving fits costume code for the comte de Morny’s ball, where the Louis XV era was the theme, but escapes the social codes that Me Duval so firmly recalled. The most interesting aspect of this case lies on another level: that of the application of these sartorial codes to masked and costume balls. Unique to the time, the social function of clothing (distinction and status identification) was thus applied to a universe that a priori ignored it or sought to subvert it. This being said, the idea of a “suspended time” of masquerades – a temporality that allowed one, in all impunity, to break through norms, and allowed deviance that social codes condemn – was not always consistent. The dominant interpretation on masquerades built on this reading finds here a manifest limit: the social sphere and the world of masquerade parties were not fully separate, and the norms of one weighed undeniably on the other30. Indeed, what Duval’s plea shows is the rigidity of views that resisted the separation between the règles du jeu and social order, and that, even for a costume ball, determined the moral conventions that weighed on young girls. In this sphere, even dressing up could not be fully subversive and costumes had to visibly confirm the wearer’s status. Even the very revealing but also very luxurious costumes of provocative aristocrats like the comtesse de Castiglione or the comtesse Rimsky-Korsakov testify to this in their own way: the baring of their bodies was accompanied by a stylistic richness that validated their place in the social hierarchy.

This paradoxical entanglement of norms that made costume balls spaces of social consolidation, in a temporal order that they were not to not disturb, explains the very strong stratification of these balls, as Léon Duval reminds us. To comte Morny’s ball, which required high fashion and utmost decorum, he compared the bal de l’Assomoir for which Delphine Baron would have been the ideal couturier and the costumes would have been a perfect fit…for a chambermaid.

Chaix d’Est-Ange chose to tread lightly on the matter of the intrusion of social codes in costume balls. He reminded us that while trying on the dresses, the baronne hadn’t find the bodices too revealing. Plus, one need only resew a few hooks for the dress to fit less tightly – something so easy to do that it was indeed carried out to tighten one of the bodices which was too wide. It’s thus on another terrain that he argued his case – one which opposed the frivolous world of the Russian aristocracy to the hardworking and useful world of dressmaking. He displaced the argument to a whole separate battlefield of norms.

“It would oppose French grace and French taste, if couturiers wrote the laws”31

To the crimes of immodesty of the costumes, Mr Duval added what would constitute one of the trial’s main points: accusations of deviance and incivility against the maison Baron. The norms on trial weren’t just those of the propriety of the two young girls, but those of hierarchy and social relations.

“Why did they occupy the sofas with such plebian verve?” With those scathing word, Duval said all that needed to be said on the conception of the world that underlay his case. He sought to reaffirm the social distinction between his client and the dressmaker or, to take a term from the old regime, the aristocracy and the commoners. He accused the workers sent by Delphine Baron of behaving without respect for the baronne de Korf. He employed belittling language that was common for the time and associated “grisettes”, or garment workers, with easy women: those “with loose tongues who are far too accustomed to masked balls.” In doing so, he adopted the stereotype of femininity structured around two poles: the one, orderly and placated, that the domestic virtue of the baronne de Korf and her daughters embodied; the other, deviant and improper, typified by female workers or actresses, who had a long tradition of being associated with prostitutes32. From the very beginning of the trial Duval pitted these worlds against each, citing seamstresses as saying “the costumes weren’t too revealing, and they are worn in high society, like at all the theaters on the boulevard.” While shrewdly hinting at Delphine Baron’s past as an actress, he also condemned the foggy normative horizons of women who thought that “high society” was found at the “theaters on the boulevard.” The “boulevard” in question was the boulevard du Temple (which led to Theatre de la Porte-Saint-Martin). The “boulevard of crime,” as it was known, was where melodramas played out nightly, thus giving the street its name33. The boulevard drew a large public of bourgeoises, trying to “slum” it, and artists, who were fascinated by the scene; but the largest public was made up of the working class. (That is, until 1862, when the theaters were demolished under Haussmann’s command.) In the hierarchy of Parisian theaters of the 19th century, the boulevard of crime was an area of “threepenny theater” and of Carné’s Enfants du Paris. It was a place accessible to all, mixing theatrics, fairground stalls, street spectacles, popular cafés, and “bouis-bouis” (greasy spoons) to quote the prefect of the Seine who had them torn down without hesitation34. For the social elites it was a place of licentious behavior, even depravity, and Duval’s evocation of it permitted him to link fashion workers to perverted coquettes.

His arguments and the allusions they conjured served to discredit Delphine Baron’s voice, as represented by Chaix d’Est-Ange, while relegating the fashion world to a universe neither moral nor respectable. Meanwhile, Duval’s case opens another, more fertile, trail that shows how far the stakes go beyond a mere question each party’s credibility. After Chaix d’Est-Ange remarked that only an expert appraisal could tell if the bodices were really too revealing, Duval retorted:

An expert appraisal to know if a dress fits well! One might as well have an appraisal to know if a mouche (fake beauty mark) is well placed. I maintain that in these matters, even in a country of equality, ladies are sovereign, and it would oppose French grace and French taste, if fashion designers wrote the laws. That a mechanic might not submit to the judgment of an industrialist for whom he creates a machine, I’ll concede. In these cases there are precise known mathematical conditions […] But in matters of clothing, it’s individual taste that decides. […]

Labruyère said it best: ’…only a philosopher lets his tailor dress him.’ Indeed an article of clothing can very well fit us, while still being in poor taste.”

Here, Duval defended the role of the nobility as sole arbitrators of taste. This hierarchy had classical and old regime origins and ruled that the client had sovereignty over the dressmakers. The supremacy lay in the client’s “individual taste.” The tailor was reduced to a “maker” who merely executes a command, and for whom resisting orders would be folly. This is what was at stake at the heart of the trial: the trial was fought over defending the “norm” confining the couturier to executing a costume for which the client brought a model, which was being singularly eroded from 1850 to 1860. Worth, considered the father of haute-couture, had founded his house in 1858. There, he sold his own creations, fruits of his imagination, and showed them on history’s first models. It was his job, then, to decide what was worn. Other names, less known today, also played a role in the “coronation of the couturier”: Staub, cited by Duval, was the most famous tailor of his time according to Balzac, who immortalized him as Lucien de Rubempré’s couturier. Dusautoy, also cited by Duval, was Napoleon III’s tailor. Humann, who Gavarni drew for, reportedly told one of his clients, “Do you know why there are so many badly dressed people Monsieur le Marquis? It’s because people want to choose their clothes instead of choosing their tailor.” These emblematic words aptly summarize what was to play out: the rise of “artists” instead of “makers” and the consecration of couturiers “who wrote the rules”, thus dethroning the aristocracy and contesting its multi-century monopoly on launching trends. This movement came with a new appreciation for the craft of couture. France entered the age of the “arts du vêtement”, heralded by the support for and affirmation of reputable modistes like Delphine Baron (before the striking masculanisation of “great couturiers”).

This court case reveals the tensions that accompanied the passage from one normative system to another. It shows resistance to the new model, marked by the disappearance of those old conventions that had contributed to the identity of the nobility. When Duval affirmed that the glory of tailors like Staub came from their clients who, after refusing a number of outfits, ended up accepting one, it signified the persistence of this representation that submitted the couturier to his or her client. The trial of 1859 brings to the light what could have represented, for some, the end of the old regime of fashion. This is the meaning, at heart, of Duval’s words: “when one is naturally noble in this world; I mean naturally by blood, by ancestry, by speech, by education, by savoir-vivre, one is at least equal to madame Baron.” This statement is an implicit example of the quasi-defeat of birthright versus talent in this quarrel over definitions of taste.

Facing this aristocratic defense, one carried out on the premise of the social, moral, and cultural subordination of clothing “makers,” Chaix d’Est-Ange gave another reading. His took into account the social realities of the fashion world to ultimately flip Duval’s argument and show the frivolity and vacuity of the baronne’s milieu. Chaix d’Est-Ange pitted the labor of craftsmen against aristocratic caprice. He first highlighted the feverish hours of a fashion atelier in mid carnival: “Try to picture the activity in the maison Moreau et Delphine Baron at a moment like this: understand how many demands must be responded to, how many specifications must be met; one doesn’t sleep, one doesn’t rest; it is, pardon the expression, a veritable battlefield.” Filled with balls and parties, carnival was one of the busiest times for all fashion houses in the 19th century. Seamstresses worked late nights, often until 11 pm (legislation began to regulate hours in 1892). Chaix d’Est-Ange reminded his audience that a worker and then the première demoiselle were sent to the fitting at 9 pm, only to leave the Hotel Richmond at 10 in the evening. This incessant coming and going defined the production of clothes under the Second Empire, a system which was only interrupted by the advent of centralized department stores. There was the coming and going of “trottins”, young workers tasked with delivering clothes to clients; there was the coming and going between fash- ion houses and the ateliers providing specific adornments (such as the garlands of roses that Chaix D’Est-Ange reminded had to be specially ordered).

It was also a time of cutthroat commercial competition, leading the Chaix D’Est-Ange to argue, in order to deny the legitimacy of the opposition’s witnesses, “one has only to present a designer with a dress not made by her hands for her to find fault in it.” The eves of balls became, in the lawyer’s words, veritable “battles to be fought” and the baronne’s demand was blind to this reality. She “demands what? Two new outfits for her daughters; and for what day? For the second of March […]. Two new outfits at such a time, two costumes to deliver in three days, when already madame Baron had turned away 20,000 francs of orders; it was impossible.” His tone become caustic and ironic when feigning understanding the baronne’s stubbornness: “this despair, I can understand: it’s about going to a ball, going to a costume ball, and going to a costume ball at M. de Morny’s.” He painted a picture of her harassing the couturier until Baron agreed, “vanquished, worn out by her insistence.” The contrast of the two worlds is apparent in Chaix d’Est-Ange’s argument: the vacuity of a ball carried out in deference to aristocratic codes versus the unhappy complacence of an overworked couturier, thanklessly repaid with a trial and with shocking “etiquette.”

The question of decency thus changed hands in Chaix d’Est-Ange’s defense. At the same time he resolutely undermined the aristocratic order of society as defended by Duval. To his eyes the hereditary nobility that Duval evoked did not hold: Delphine Baron believed she was dealing with a schemer and the baronne’s “strange, colorful language” and the “no less energetic way in which she greeted the première demoiselle” reinforced this belief. The language conventions signaling social class, that Duval evoked to highlight the workers’ deviance, were turned around against the baronne. Chaix d’Est-Ange played with this idea of hereditary nobility from the start of the trial, exclaiming: “one must admit that madame Korf understands business; she commands costumes, doesn’t pay for them, and demands 3,000 francs! She’s born for commerce.” He even dared to counter his opponent’s argument note for note on matters of decency and good taste. He first noted how Delphine Baron took care to make the bodices higher than those in the provided engraving. He lingered, with especially biting irony, on the baronne’s misunderstanding of high-society conventions: “At ten o’clock! That was too late? One only has to note that the invitations stated ten o’clock and that, however much one desires to not miss a second of the ball, coming before ten thirty leaves one to see the chandeliers lit and the parquets waxed. Just because the de Korfs are foreigners isn’t reason enough for them to arrive like provincials.”

More than in a simple “affaire de chiffons”, the trial shows how outlines of a power conflict were drawn in an era in which the nobility began to lose their status of the arbiters of fashion and taste. The trial becomes the site of a class battle. The contrast between the imperial parties and the working class realities that prop them up are clear. The outlines of two antagonistic worlds of thought, each displaying the singular and unexpected politicization of their respective arguments, come into view. Behind the supposed immodesty of two bodices, a conflict of norms plays out: one that pits France – daughter of the Revolution, land of equality, civil law, and rights – against Russia of the old regime, all serfs and knouts.

“I don’t know if in Russia they still treat their serfs this way…”35

Beyond the conflicting norms of decency and the commercial contentions, the lawyers’ arguments gave the affair a third, political dimension: a conflict between the Ancien Régime and the new society. There are a plethora of references to 1793, to equality, to the Napoleonic code, to the tricolor flag, to serfdom, and to noblemen. Astonishingly, another confrontation of norms played out during the trial: one that opposed a conservative social worldview, as espoused by Mr. Duval, against a worldview of judicial and hereditary equality, as defended by Mr. Chaix d’Est-Ange.

Duval’s case was filled with denunciations of what he presented as fanatic egalitarianism: that of the fashion workers and bailiffs sent by Delphine Baron, who he depicts as violating social hierarchies and mistreating titled elites. “They say that, in a country of equality, the wife of a landowner was never worth more than another, that there were never serfs in France,” he stated. To this reoccurring accusation, he added one of incivility: “one fears no one, and […] ladies can sit on chairs, the sofas being occupied.” The trial thus shifts from a crime of immodesty to a crime of contempt for social distinction. This argument was inapt for Me Chaix d’Est Ange, who countered: “whether the bailiff sat on a chair, a couch, or a stool, I admit is difficult for me to defend, since I didn’t ask my client’s advice, and since I regard it as inconsequential to the trial.” It was, however, one of Me Duval’s main points. He turned this egalitarian protest into both a diplomatic and a social menace. Not hesitating to dramatize the trial’s potential echo, he proceeded: “Misfortune for luxury merchants! Misfortune for designers if we get entangled with Russia!” To his eyes, the stakes had come to encompass the name and reputation of France: “it must not be that abroad they imagine that once the Napoleonic code was established, civility disappeared.” He thus repeated a trope, born in an earlier era of anti-revolutionary thought, of how revolutions led to vulgar morals by breaking with the tact and grace of past centuries. At a time of improving relations with the Russian autocracy, for workers to defend an “equal France” was, in his eyes, a dangerous provocation, perhaps even a breach of diplomacy. Furthermore, the menace was social as well as diplomatic: “there was a time when the Châtelet bailiffs were in a perilous state; nobles would thrash them. We thought this poor and for good reason. But this depravity was amply avenged in 93. It must not be that today, it is the bailiffs who thrash the noblemen.” For the baronne’s lawyer, the danger was clear: the social order was under threat, and its inversion could lead to a carnivalesque state where the nobles were indeed thrashed.

To counter this argument, Me Chaix d’Est-Ange, chose to denounce the brutality of a Russian aristocracy riddled with arbitrary conventions36. He reminded the court that the première demoiselle “was received… I cannot tell you how; I don’t know if in Russia they still treat their serfs this way, but in France, there are few noblewomen who would free themselves enough to take this kind of liberty with language.” The conflict then became one of political cultures, with Chaix d’Est-Ange ironically summarizing:

Madame de Korf didn’t content herself with demanding damages, she also accused the solicitor and the bailiff. In Russia they would have used the knout against them all, but in France the knout doesn’t exist. It’s unfortunate, but it doesn’t exist. While waiting for this regrettable lacuna to be rectified, we must content ourselves with lawsuits. […].37

His case led him to pit aristocratic pretense – Nabokoff, “who, assuredly, is a very noble man in Russia” – against the brutal reality underneath, and, by extrapolation, the striking incivility:

Nabokoff proposed to the bailiff, in his words, to ’throw him out of the window’ and I must admit, I am forced to conclude that the bailiff had the poor taste not to jump; I must admit that he may have displayed some irritation, and in truth it seems to me that many honest men would have done the same.

Thus Chaix d’Est-Ange threw his adversary’s autocratic tone back at him, resolutely putting the case on the terrain of rights and judicial equality. The conclusion of his defense was unsparing:

there it is men, this trial, from which we can maybe glean a small moral – that when we order clothes, we must pay for them; that the law is made for madame la baronne de Korf as it is made for everyone; that in the end, in France, bailiffs have the right, that we cannot find too exorbitant, to disagree with even someone like Mr. Nabokoff wanting to throw them out of a window.

Who then won the trial? Me Léon Duval, “the fine swordsman, the master of the sharp epigram” according to Le Monde illustré or Me Chaix d’Est-Ange, the young, witty lawyer who that day accomplished “the most beautiful tour de force” possible “on a needle’s point” according to Le Figaro?38 39 In this duel the victory was handed to the baronne: Delphine Baron was condemned to pay 1,000 francs in damages for the seizure of goods against madame de Korf that the prosecutor found so vexing. The victory however was partial: a second opinion was ordered at the end of the trial.

The victory also shrouds a mystery: according to Chaix d’Est-Ange the costumes were worn. No sources, however, allow us to confirm or deny this statement. The victory was surely short term; the balance of power that would later shift in favor of couturiers. Le Tintamarre predicted:

a day will come for vengeance. […] So lawyers, you’ll have your mouths shut and Madame Baron will cut the thread of your arguments. Be careful sirs of la Basoche, you who, at a certain time talked so fluently of clothes and costumes; what will you say if you’re one day obliged to appear before a tribunal of seamstresses who, judging sovereignly and without appeal, will introduce great changes in the strict costume of your profession […]. You will no longer be able to declare these poor seamstresses incompetent; and you who pleaded so well for fashion and good taste, you will be force to submit without so much as a murmur of protest…

And the end of this little story we hope to have shown to what extent affaires de chiffons crystallize complex norms: how trials such as these reveals the games of power and of hierarchy and the power of social representations, scales of economy, and political representations. We are far from trivial matters and much closer to the spirit of a time.