“Ball is a place to express the suffering you feel and be able to invent your life.” Lasseindra

A dancing fashion show full of mocking gestures

We meet Yanou and Kylee along the banks of the Seine, between chic cocktail bars and refugee tents, across from the Austerlitz train station. They’re sitting and sipping beer out of bottles and aren’t in a rush, even if they’ll be dancing in a half hour. This evening, there’s no theme for the ball so they don’t need makeup or costumes. Yanou is wearing a floaty gray “Harry Potter Indesirable n°1” T-shirt, slim jeans and espadrilles, Kylee has on a wide-brimmed baseball cap, loose tank top with smiley faces, slim jeans and high-top sneakers. They’re getting ready to dance at Wanderlust. The club is worried about attracting a voyeuristic public for this show of young transvestites from the suburbs. But Yanou and Kylee aren’t worried, they could care less about the location. These “Crème de la crème” evenings are organized by Lasseindra, their House of Ninja “mother” who knows how to protect the “sisters”. Some gawkers pass but the Voguers feel at home and quickly make us forget the club’s boring trendiness. They know how to nonchalantly resist any attempt to distort what they do. The show has been announced for 7 PM but begins, with no explanation, around 10 PM.

A stage is quickly put together with velvet ropes separating it like those used outside night clubs. The jury on one end of this impromptu runway is made up of Sky, a House of Ninja dancer, a professional dancer who looks like Tupac and is a regular at these battles and a man in a panther outfit with huge sunglasses like those of a 1960s Pan-African intellectual. On the other end of the stage is the DJ and against the ropes squeeze in the Voguers and their friends. This evening, the ball is against the House of Ladurée. It opens with a few blurry passages of Voguers who are constantly teased in jest. Though Voguers may elude our total comprehension as they twist social codes, they’ve developed amazingly complex, arbitrary codes for dancing and ball rituals made up of elaborate taunts. The show begins and a loud, husky-voiced speaker with pointy breasts, tottering on stiletto heels, delivers a flow of rap lyrics to a hip-hop, sometimes house beat. Mixing English and French, she comments on each passage, lauding the successes and mocking the failures The cheering public accompanies her in a monotonous chant that supports or puts down the candidates being voted on. Because Voguing, like rap battles, is a reading of flowing mockeries – or a shade, the version of rap with insults. Though Voguing is intentionally homophobic in its approach, the participants do have to protect themselves from everyday homophobia.

Jeers are essential since the public must choose its camp in a succession of duels. The eliminations happen immediately, decided by the jury and echoed by the crowd. The public sides with its House: this evening, it’s torn between supporting House of Ninja and House of Ladurée – passages evoke a single cry from some or “sugary, savory, House La-du-rée” from others. Both Houses imitate a competition and make sure to contrast their styles. The House of Ninja intentionally cultivates the style invented by Willi Ninja in the 1980s. He was a great admirer of Fred Astaire, the martial arts and Olympic gymnasts’ gestures when he created his house in New York. But House of Ninja Paris has its own style, encouraged by Lasseindra, that’s full of spectacular falls and boastful humor. The competition style also mimics celebrity wrestling matches or burlesque shows as candidates bump into each other, collapse or imitate being wounded … In the 1980s they imitated knife fights – and when the results were announced, they’d cry scandal and collapse “wounded” to the ground or shout that the competition was rigged… like a beauty contest gone awry.

Glitter and sport socks

For the neophyte, the fashion show categories are inscrutable. With irony, the Voguers try to explain this to us – but nonchalantly. Some are Old Way, others are Up in Drag, Vogue Fem, Butch Queen Face, American Runway, European Runway… Though they don’t use slang terms like Harlem’s Pig-Latin Voguers did in the 1980s, they do play with words. Finally, the only thing that’s really clear is that the term Voguing means reworking the poses seen in Vogue magazine. The shows parody women’s magazine poses, haute couture shows and beauty contests – trophies are even awarded at big events. There are also themes, as in the 1980s, that range from “The Face of Cleopatra” to “Hollywood”… For these evenings, Voguers put themselves together carefully, assembling second-hand clothes and disguises or making them with cardboard that they cover with fabric or paint. Intentionally outrageous wigs and makeup complete the transformation, though many keep masculine attributes like trimmed beards or hairy torsos.

But costumes aren’t essential: many shows are done in everyday clothes. Like this evening at Wanderlust that announced “come as you are” on the invitation. Kylee, who sometimes dresses as Naomi Campbell in a fur coat and chapka with her non-stop legs, dances this evening in an H&M T-shirt, stretch denim shorts and sport socks – a classic accessory for Voguers. The subversion seems even more radical: the ball and its music hall feel allow for cross-dressing that gives it a carnival look. So the transgression is double with a T-shirt and socks: Voguers explode heterosexual codes as well as the codes of mainstream gay culture, weighed down by the clichés of ideal physiques and clothing standards.

Back to the suburbs

By midnight, the room empties with the “last” RER, there’s less hesitation to leave since its a week night and many work the next day. Some are doing job internships, others just passed the baccalaureat, a few seek low-paying, unstable “day jobs” in fast food chains or clothing stores. Yanou is surprised that despite his “beautiful face”, no employer contacted him after he sent out over 20 resumes listing job experiences ranging from Auchan Drive to a dance performance for Hermès. There’s no typical profile. There are also middle-class kids but most Voguers are from “lower class” suburbs: Charenton, Villiers-sur-Marne, Romainville, Champlan… Not necessarily “tough” neighborhoods but where it’s not easy to be gay. They are all from the immigrant community: “rebeus” (slang for Arabs) or “renois” (slang for blacks) including many from the French West Indies. Lasseindra is from French Guyana. And all are gay and proud of it, pointing out that, compared with other “churches”, House of Ninja Paris maintains a gay and militant aspect.

Houses made up of “mothers” and “sisters”

The week before, we had an appointment, organized a few weeks earlier with Lasseindra, to do a photo shoot in a 20th arrondissement studio. Everything passed by her. I met her in the Summer of 2013 near the music stand across from Charenton City Hall. Lasseindra was annoyed, she said that none of my questions made sense. She was cautious after having had bad experiences with the big fashion magazines. We made an appointment for the following month; it took place a year later. We talked about the conditions for taking photos of House of Ninja members. Lasseindra insisted on a contract to protect the girls and the right to choose the images that would be used.

In July 2015, the day of the photo shoot, she came to verify everything and signed the contract as “sisters for the contract”. Being the House of Ninja “Mother” means accompanying her dancers as any dance troop manager would do. But the House is more than that: it’s a substitute family as were the Harlem Houses of the 1980s and 90s for Latino and black gays. Having either broken away from their real families or in a delicate position with them, they find refuge here. Symbolically, without ambivalence, they abandon their family name and replace it with “Ninja”. And this chosen family cultivates its genealogy. Lasseindra calls the members her “babies” and they call each other “sister”. This new family, with its ties of solidarity, creates an obligation, especially for protection.

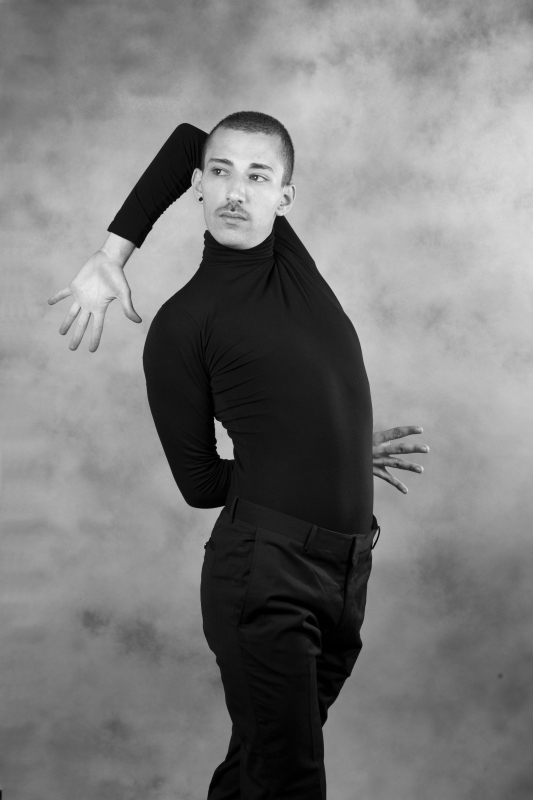

Poses

Installations and lighting tests continue as we wait for Lasseindra. At the end of the morning, everyone is here. After jokes about the neighborhood “that sucks because it’s impossible to find a KFC [Kentucky Fried Chicken]”, two leave to pick up McDonald’s menus. Tess does everyone’s makeup. Kylee has a towel knotted on her head so her long hair – that she doesn’t have – doesn’t interfere with her makeup. In the studio kitchen transformed into a dressing room, the Voguers open their sport bags and get dressed.

They know this is a show where only the effect and gestures count. Thus they don’t spend much for their outfits – usually GAP, New Look, mass market brands or counterfeits. It’s not about money: though they cite brands in the show, especially luxury ones, they have little importance in Voguing. It’s how everything is put together – the creation – that counts. The clothes are a game and a disguise. It’s not about good taste, Voguers are elsewhere, they set their own taste and play a game, a far cry from the sober uniform of chic Parisian women. They hold their outfits together with the paper clips, rubber bands and safety pins they store in their pencil cases. They know that magazine fashion is all about image – they piece everything together quickly as fashion photographers do.

Histories

A Voguer, waiting to be photographed while smoking a joint at the window, recommends looking at the photos by Chantal Regnault, a rare report about New York’s 1980s voguers that tells a passionate story about Voguing. If Voguers dress up and exaggerate clichés, they also shake up sociological stereotypes. The idea that “authentic” subcultures have no history, since they’re spontaneous, is clearly not valid. Each voguer tells her own, sometimes mythical, sometimes detailed, story of Voguing. They’ve all seen Paris is burning – the name of an evening – by documentary filmmaker Jennie Livingston, first shown in 1990, and they know one of its stars is Willi Ninja. They all have an opinion about the phenomenon and its resur- gence. There’s nothing artificial about it: a young homosexual from an immigrant family who gets into Voguing can’t do it halfway. Thus they don’t want to be seen as “folklore” – they’ll participate in special events and appear in video clips but are cautious when the concept is vampirized.

Voguing – a story yet to be told – can be traced back to 1930s New York, a time when the “ball culture” developed. Then it was practiced by white people and based on beauty pageants, dance competitions or fashion shows. Participants even received awards for their costumes. Black people were rare and only existed here by parodying their own identity or performing in whiteface. Actual traces of these practices done by black homosexuals can’t be found – which doesn’t mean they didn’t exist. In any case, Voguers like to go back to this mythical age that rooted Voguing in the margins of society when minorities fought against social oppression.

Some black homosexuals did begin to assert themselves by organizing balls in 1960s Harlem. They were a cross between a fight against segregation and the fledgling LGBT movement. These Harlem Drag Ball evenings resembled costume balls with participants dressed as Hollywood stars, historical characters from Cleopatra to Marie-Antoinette or popular singers … and the glittery costumes were inspired by show biz. Though some saw traces of gay culture in the Harlem Renaissance movement, it was generally not accepted, less for its fight against segregation with cultural and religious overtones and more because of its paramilitary or virile looks. But the times clearly changed after June 1969 when the Greenwich Village Stonewall riots, a few kilometers from Harlem, gave a new visibility to the gay movement and made it political. The next year the first “gay pride” parades in New York and Los Angeles made it easier to express one’s homosexu- ality publicly and helped end the strong police repression, especially in New York where it was forbidden to cross-dress, serve alcohol to homosexuals or let men dance together …

In the 1970s, the movement developed but was more organized. The first House was created in 1977 by Crystal Labeija. Meanwhile in San Francisco, the White Night Riots – following the feeble condemnation of Harvey Milk’s assassin Dan White – brought the homosexual question to the forefront, Houses opened out- side New York in cities with a strong black culture like Baltimore, Washington and Atlanta. They offered shelter and protection to young, runaway homosexuals who were often under-age, had been rejected by their families and often had the pre- carious existence seen in Paris is Burning. They had low-paying day jobs, some worked as nightclub strippers and a small percentage were even prostitutes. They did mopping, a slang term for shoplifting. But in the evening and often all night long in Harlem – at 10 West 129th Street – the cards were shuffled differently. Voguers, sometimes holding a fashion magazine, aped the extreme femininity seen in the press and advertising. And they played with masculine, heterosexual codes by using categories dedicated to military men, Ivy League students or Wall Street yuppies… At these Harlem nights, penniless, prancing youth mimicked the success standards typified by Manhattan as they joyously mocked normality with their exaggeration and excess.

In the 1980s, the movement underwent a double mutation. With the appear- ance of AIDS, Houses took on a new importance since solidarity and support were essential for dealing with illness and Voguers’ rejection by their families. Mean- while the ball culture was increasingly visible. In 1990, when Paris is burning was released to a moderate success, Madonna, already a power to be reckoned with, introduced Voguing to the general public with her Vogue clip. Houses multiplied. Some used the name of their founder: House of Pendavis, House of Duprée, House of Corey, House of Ninja, others promoted their identity: House of Ebony, House of Overness… while some intentionally took a brand name: House of Saint Laurent, House of Dior, House of Chanel, House of Miyake-Mugler, House of Balenciaga, House of Ladurée… Was this authenticity lost on show biz society? By 1989, Willi Ninja was nostalgic for the old balls and the disappearance of the musical and social life on New York streets … If Paris is burning was a swan song, it expressed a longing for this world before AIDS appeared.

Genealogies

But Voguing is alive today and its reappearance isn’t a surprise. Its development could have a relationship to the gay culture in 1920s-1930s Paris. Today the culture operates underground, like hip-hop. As the fruit of multiple exclusions and overturned standards, it has every reason to continue. In contrast with what sociology claims, popular cultures don’t live once, and their reappearance is not necessarily commercial or even led astray … Knowing about Voguing’s history doesn’t take anything away from its authenticity. Today’s Voguers may redo the 1980s Voguing of Harlem’s black and gay Latinos but their approach is neither quaint nor precious. These Voguers are black, Arab and gay in a world that excludes them from work because of their origins, gay in a society that rejects them because they’re homosexual and, in the gay world, they’re ostracized because they’re poor. For them, the connecting thread of this story has never broken. Lasseindra still refers to Willi Ninja, who died in 2006 at the age of 45, as “grandmother” and Archie Burnett, a black dancer who vogues as a man, as “grandfather”.

The sisters are amused by the photos taken of them and choose shots for their books. They are awaited at another event so they quickly remove their makeup and leave, some laughing at the traces of makeup still on their faces. They expect they’ll inspire a few reactions on the street.

Portfolio : July 8th 2015, Paris 20th arrondissement

https://devisu.inha.fr/modespratiques/240?file=1

Bibliography

Molly McGarry et Fred Wasserman, Becoming Visible: An Illustrated History of Lesbian and Gay Life in Twentieth-century America, New York, Penguin Books, 1998.

A. B. Christa Schwarz, Gay voices of Harlem Renaissance, Indiana University Press, 2003.

Marlis Schweitzer, When Broadway was the Runway: Theater, Fashion and American Culture, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009.

Voguing: Voguing and the House Ballroom Scene of New York City, 1989-92, photographs by Chantal Regnault, Introduction by Tim Lawrence, Soul Jazz Books, 2011.

Tiphaine Bressin et Jérémy Patinier, Strike a pose : Histoires(s) du voguing, Paris, Éditions Des ailes sur un tracteur, 2012.

Documentaries

Jennie Livingstone, Paris is burning, 1990, 78 mn.

Frédéric Nauczyciel, Vogue ! Baltimore, 2011, photographies et installation.